|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

Even had Shakespeare never written for the stage, the dramatic literature of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries would remain the richest corpus of writing in English literature. With a growing praise for Shakespeare’s craft and attendant "Bardolaltry" over the centuries, however, the work of his fellow dramatists inevitably and regrettably diminished. This course will bring to the student's attention the exciting and varied offerings of Shakespeare's contemporaries, as well as one atypical play by Shakespeare that many insist he did not write.

We will begin with the two most popular plays of the Elizabethan era, Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus and Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy. Tradition had it that after the first performance of Doctor Faustus the devil himself appeared on stage whenever the play was performed, frightening the audience and threatening damnation to those in attendance. Yet Kyd's play of murder and revenge was the most popular work of the Elizabethan era, drawing crowds that no other play, not even those of Shakespeare, could equal. Nonetheless, Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus came close. This remarkably violent, bloody play became, in act, the most popular of Shakespeare's works during his dramatic career.

The focus of the course will then shift to the plays of the Jacobean stage, after 1603, when a new mood took hold of the dramatists and audiences of London. Stage offerings were dark, brooding renderings of the macabre that provided psychological profiles of evil, coupled with horrific events. Cyril Tourneur's The Revenger's Tragedy remains one of the most disturbing plays of the era, while John Ford's 'Tis Pity She's A Whore—not for the feint of heart—puts a new spin on Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. Even comedies, such as those by Ben Jonson, frequently engaged their audiences with dramatic narratives of charlatans, thieves, and mountebanks who met with bad ends. The Alchemist, one of the finest-constructed plays ever written, depicts an assortment of "honest citizens" and Puritans whose only interest is greed: the magician's art of turning base metals into gold. We conclude with John Webster's The White Devil, a tragedy of remarkable psychological insight into a female protagonist who confronts the villainy of her own desires as well as that of a corrupt society.

The course will familiarize students with an extraordinary selection of plays that both shock and delight, but are never boring. Ultimately, the student will find that Shakespeare was less an anomaly of his age than one of its many master playwrights.

This course will focus upon plays as products designed for the theatre. To appreciate those plays one must hear the verse, see the performance, and imagine the images; merely reading the plays is not enough to fully understand the beauty and power of a stage play.

Too often students are confused or put off by the poetry (and prose too) they find in Renaissance plays and turn instead to Cliffs Notes, or Monarch, or some other guide for the plot—the bare "facts" of the story. This is regrettable since it reduces dramatists to storytellers and neglects all of their art. The story of Hamlet was not new with Shakespeare, nor was King Lear, nor all but two, perhaps three, of his plots. Other dramatists did much the same--their plots were mixtures of historical incidents, ancient texts, borrowed ideas from contemporaries, and innovative ideas. In the Middle Ages, "creativity" was an example of pride--a terrible sin, because it was the cause for the Devil's fall. The Renaissance was less restrictive with regard to originality, but the age saw the creative spirit as that which improved upon existing forms rather than the imitation so strongly adhered to by medieval artists.

Primary in a true appreciation of Renaissance drama is the poetry. The theatre of their day was a poetical one. Rather than being confused by the poetry we find in these plays, we need to understand why the poetical theatre was, and is, superior in expression and more powerful in emotion than a realistic one. Their stage was "conventional"--or poetical--while today's stage is realistic.

Appreciating the poetry is not an "acquired taste," like drinking scotch or eating clams, but requires an understanding as to what the poetry is doing, what it conveys and why. Note that you can understand the language. Today, for instance, more unknown words are used on MTV than we encounter when looking at these plays; yet, we have no trouble understanding the context for the words when viewing MTV and thus understand their intended meaning.

But words alone are frustrating. In a realistic theatre words alone cannot express experience but require action to bring them to life or give them meaning. Poetry, however, expresses emotion; it conveys feelings through images. Thus poetry provides a language for feeling that also creates an imagistic picture which goes beyond the mere words used to convey that feeling. Poetry also permits us a great range of expression, a subtlety of thought and emotion that captures our true feelings.

Let's take, for instance, a poem familiar to most of us, even if we don't know who wrote it or why.

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and ideal Grace.

I love thee to the level of every day's

Most quiet need, by sun and candlelight.

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise;

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood's faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints--I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears of all my life!--and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

(Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Sonnets from the Portuguese, no. 43)

This is an expression of the love one person feels for another, an expression that in each of its lines imparts a particular and subtle form of that love. It's far richer and more meaningful than simply saying "I love you" or "I love you more than anything else I can think of." Now imagine that instead of words written in a letter or book proclaiming that love the words were part of a story or action played out on a stage. On a modern stage the prose might state

My darling, I've never loved anyone else as much as you. You're my everything. Without you I'd be lost. You know, I love you deeply. No one forces me to feel this way, I just do. You're my religion, my dreams, my very life. And tomorrow, God willing, I'll love you even more.

Obviously at some point the words become repetitious, almost meaningless, because they need a context in which they're spoken. They need action to bring them to life. Spoken cynically or sarcastically there's another meaning entirely. But prose written well, without the flat, meaningless repetition, approaches poetry: it has rhythm, subtlety, gradations of meaning, and it conveys an image--which provides the context for the language. The strength of poetry is that it allows us to find or express just the right feeling, the perfect mood or state of mind.

Now take this same idea of one person offering love for another as it appears in Shakespeare, when Juliet says in response to Romeo's request of her vow of love:

And yet I wish but for the thing I have.

My bounty is as boundless as the sea.

My love as deep: the more I give to thee

The more I have, for both are infinite.

(Romeo 2.2.130-35)

Finally, the poetry in these plays says more than prose can because it isn't confined to a literal meaning, as is the case with realistic theatre, but suggests ideas through associations or likenesses--what are called metaphors. As an example, in Shakespeare's Timon of Athens Timon is disgusted with mankind, hating all of the supposedly "decent" people he knows. When confronted by thieves he tells them to go about their work merrily; everyone steals, and he offers examples of thievery:

I'll example you with thievery:

The sun's a thief, and with his great attraction

Robs the vast sea; the moon's an arrant thief,

And her pale fire she snatches from the sun;

The sea's a thief, whose liquid surge resolves

The moon into salt tears; the earth's a thief,

That feeds and breeds by a composture stol'n

From gen'ral excrement; each things's a thief.

(Timon of Athens 4.3.438-45).

In short, what you need to do in this class is to get drunk on the poetry; intoxicate yourself with the words and the images. Poetry is the strength of these plays, separating greatness from the day-to-day and offering a great variety of meaning and interpretation.

General Introduction:

Renaissance

Drama in Shakespeare's

Day

A

s a general introduction to the Renaissance Drama there are several areas of background information that will prove helpful to your enjoying his plays.F

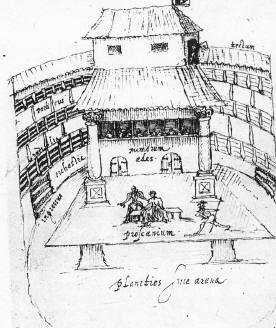

irst, remember that these are plays first, meant to be performed on a stage with the needs and reactions of an audience always to be considered. Even when we appreciate the dramatist's work as literature, an understanding of the Elizabethan theatre and how it operated aids our knowledge.The London theatre during the last years of the reign of Elizabeth was an exciting place. In a city of some 100,000 people, perhaps as many as 15 to 20,000 people attended the theatre each week, even though plays were presented during mid-day, when practically everyone had to work.

From 1594 to 1600, two theatres operated in London and shared the crowds. The

Chamberlain's Men (for whom Shakespeare wrote and performed), while the other

company was the Admiral's Men. Their theatres were similar: large, octagonal

buildings with three levels for spectators. The stage was especially large; a

"thrust" stage that projected out into an open area. In front of this

stage was the "yard" where the cheapest seats were; but spectators

didn't sit--they stood in a crowd at the front of the stage for their penny

entrance fee. These people, called groundlings, stood for two to three hours; in

bad weather, they stood in the mud and were rained or snowed upon, because the

theatres were open at the top. Only those who could afford to pay more sat in

one of the three tiers of seats under cover.

From 1594 to 1600, two theatres operated in London and shared the crowds. The

Chamberlain's Men (for whom Shakespeare wrote and performed), while the other

company was the Admiral's Men. Their theatres were similar: large, octagonal

buildings with three levels for spectators. The stage was especially large; a

"thrust" stage that projected out into an open area. In front of this

stage was the "yard" where the cheapest seats were; but spectators

didn't sit--they stood in a crowd at the front of the stage for their penny

entrance fee. These people, called groundlings, stood for two to three hours; in

bad weather, they stood in the mud and were rained or snowed upon, because the

theatres were open at the top. Only those who could afford to pay more sat in

one of the three tiers of seats under cover.

The back of the stage, where the actors appeared, was called a "tiring house"--short for "attiring." It too probably had three levels and rose to the top of the theatre, with an overhang at the top to protect the stage from the bad weather.

Audiences were large, excited, expectant, noisy, and demanding. Plays had to entertain them, whether comedy or tragedy, or they became restless, disruptive, and even violent. Ale was sold, as well as fruit. Pockets were sometimes picked or quarrels broke out. By all accounts, to be seated or standing, waiting for a play to begin was electic.

The Age of the London Stage

In 1600, the city of London had a population of 245,000 people, twice the size of Paris or Amsterdam. Playwriting was the least personal form of writing, but clearly the most profitable for literary men since the demand was so great: 15,000 people attended the playhouses weekly. What is often exploited in the plays is the tension between a Court culture and a commercial culture, which in turn reflected the tension between the City government and the Crown. The period we are dealing with, 1576 (date of the first public theatre in London) to 1642 (date that the Puritans closed the theatres) is unparalleled in its output and quality of literature in English.

The monarchy rested on two claims: that it was of divine origin and that it governed by consent of the whole people. The period was one of great transition. We generally regard this period of history as the English Renaissance, which took place approximately 100 years later than on the continent. The period also coincides with the Reformation, and the two eras are of course mutually related.

Imposed upon the Elizabethans was a social hierarchy of order and

degree--very much medieval concepts that existed more in form than in substance.

The society of Shakespeare's time had in many ways broken free of their

rigidities. It was not that people were rejecting their past; rather, a new more

rigid order was replacing the old. This was set into motion during Henry VIII's

reign in the 1530s when he assumed more power than had hitherto been known to

the monarchy. The "Act of Supremacy" of 1534 gave to Henry the power

of the Church as well as temporal power.

Imposed upon the Elizabethans was a social hierarchy of order and

degree--very much medieval concepts that existed more in form than in substance.

The society of Shakespeare's time had in many ways broken free of their

rigidities. It was not that people were rejecting their past; rather, a new more

rigid order was replacing the old. This was set into motion during Henry VIII's

reign in the 1530s when he assumed more power than had hitherto been known to

the monarchy. The "Act of Supremacy" of 1534 gave to Henry the power

of the Church as well as temporal power.

By Shakespeare's time we are seeing the state assert its right in attempting to gain authority in secular and spiritual matters alike. The so-called "Tudor myth" had sought to justify actions by the crown, and selections for the monarchy, as God sanctioned: to thwart those decisions was to sin, because these people were selected by God, for good or for ill.

Elizabethan political view were themselves in process of change (the deposition scene of Shakespeare's Richard II, which at one time could be staged) was omitted in the published quarto of 1597). The premises themselves of Elizabethan political though were paradoxical, being based, as derived from Henry VIII, at once on the divinity and mortality of the king's two bodies. Divinely enthroned, he is also "elected," his power being drawn from Parliament or people.

The population of the City quadrupled from Henry's reign to the end of Shakespeare's life (1616), thus adding to the necessity for civil control and law. Part of the labor market had been taken away from the monasteries and nunneries which Henry had taken over, and the number of saints days in Catholic times were now no longer in existence in a Protestant country (so people worked more hours); thus the employment problem was severe.

Puritanism, which first emerged early in Elizabeth's reign, was a minority force of churchmen, Members of Parliament, and other who felt that the Anglican Reformation had stopped short of its goal. Puritans used the Bible as a guide to conduct, not simply to faith, but to political and social life, and since they could read it in their own language, it took on for them a greater importance than it had ever held. They stressed particularly the idea of sabbatarianism, taking on a rigidity of the children of Israel under Moses, remembering the Sabbath day with such a zeal that the Sabbath never had a rest. The conflict between the "players" of the theatre--who performed for the larger crowds that would turn out for productions on the Sabbath--was established early.

The age was thus turbulent, changing (as the movement from Catholicism to Anglicanism to radical Protestantism, in Edward's brief reign, to Catholic to moderate Protestant testifies).

The English Renaissance begins with the importation of Italian art and philosophy during the same period of Henry: Wyatt and Surrey are, for the most part, responsible for the literary importations and imitations of writers such as Petrarch. While the "Great Chain of Being" (an idea suggested from antiquity; all that exists is in a created order, from the lowest possible grade to perfection--God Himself; Nature abhors a vacuum) is still asserted, the opposite, the reality of disorder, is just as prevalent. Not surprisingly, a favorite metaphor in Shakespeare's works is the world upside down, much as Hamlet presents.

The analogical mode was the prevailing intellectual concept for the era, which was inherited from the Middle Ages: the analogical habit of mind, with its correspondences, hierarchies, and microcosmic-macrocosmic relationships, survived from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Levels of existence, including human and cosmic, were habitually correlated, and correspondences and resemblances were perceived everywhere. Man was a mediator between himself and the universe. An "analogy of being" likened man to God; however, the Reformation sought to change this view, emphasizing man's fallen nature and darkness of reason. The analogy can be seen in the London theatre, correlating the disparate planes of earth (the stage), hell (the cellarage), and heaven (the "heavens," projecting above the top of the stage). Degree, priority, and place are afforded all elements, depending on their distance from perfection, God.

Because he possessed both soul and body, man had a unique place in the chain--the extremes of human potential are everywhere evident in the drama of the English Renaissance. Natural degeneration, in contrast to our optimistic idea of progress, was everywhere in evidence too--the primitive Edenic "golden age" was irrecoverable, and the predicted end of the world was imminent. With changes in the ways that man looked at his universe, disturbing discoveries suggested mutability and corruption: the terrifying effect of new stars, comets, etc., added to a pessimism that anticipated signs of decay as apocalyptic portents of approaching universal dissolution.

Hierarchically, the human soul was threefold: the highest, or rational soul, which man on earth possessed uniquely; the sensible, sensitive, or appetitive soul, which man shared with lower animals; and the lowest, or vegetative (vegetable; nutritive) soul, concerned mainly with reproduction and growth. The soul was facilitated in its work by the body's three main organs, liver, heart, and brain: the liver served the soul's vegetal, the heart its vital, and the brain its animal faculties--motive, principal virtues, etc.

Man himself was formed by a natural combination of the four elements: the

dull elements of earth and water--both tending to fall to the center of the

universe--and air and fire--both tending to rise. When the elements mixed they

shaped man's temperament. Each element possessed two of the four primary

qualities which combined into a "humour" or human temperament: earth

(cold and dry: melancholy), water (cold and moist: phlegmatic); air (hot and

moist: sanguine); fire (hot and dry: choleric).

Man himself was formed by a natural combination of the four elements: the

dull elements of earth and water--both tending to fall to the center of the

universe--and air and fire--both tending to rise. When the elements mixed they

shaped man's temperament. Each element possessed two of the four primary

qualities which combined into a "humour" or human temperament: earth

(cold and dry: melancholy), water (cold and moist: phlegmatic); air (hot and

moist: sanguine); fire (hot and dry: choleric).

Like his soul and his humours, man's body possessed cosmic affinities: the brain with the Moon; the liver with the planet Jupiter; the spleen with the planet Saturn. Assigned to each of the stars and the sphere of fixed stars was a hierarchy of incorporeal spirits, angels or daemons. On earth, the fallen angels and Satan, along with such occult forces as witches, continued to tempt man and lead him on to sin.

Towards the mid-seventeenth century a major cleavage between the medieval-Renaissance world-view and our own took place, effected by Ren‚ Descartes (1596-1650): Cartesian dualism separated off mind from matter, and soul from body--not a new idea but reformulated, so that the theologian's doctrines became the philosopher's; the problems of Predestination were suddenly the problems of Determinism.

For Descartes, all nature was to be explained as either thought or extension; hence, the mind became a purely thinking substance, the body a soulless mechanical system. Cartesianism held that we can know only our own clear and distinct ideas. Objects were important only in so far as we bring our own judgments to bear upon them. Cartesian skepticism and subjectivism led to the rejection as meaningless or obscure the previous centuries' Aristotelian perspectives. According to Aristotle, to know the cause of things was to know their nature.

Familiar to Shakespeare and his contemporaries were the Aristotelian four causes: the final cause, or purpose or end for which a change is made; the efficient cause, or that by which some change is made; the material cause, or that in which a change is made; and formal cause, or that into which something is changed. Renaissance concern with causation may be seen in Polonius' laboring of the efficient "cause" of Hamlet's madness, "For this effect defective comes by cause" (2.2.101-03). Ironically, Othello's "causeless" murder of Desdemona is prologued by a reiteration of "cause."

In the Aristotelian view, change involves a unity between potential matter and actualized form. Change is thus a process of becoming, affected by a cause which acts determinately towards a goal to produce a result. Implicit in the Elizabethan world-view was the Aristotelian idea of causation as encompassing potentiality and act, matter and mind. The London dramatist's pre-Cartesian universe, indeed, tended to retain a sense of the purposefulness of natural objects and their place in the divine scheme.

For the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, objects influenced each other through mutual affinities and antipathies. Elizabethans accepted the correspondences of sympathies and antipathies in nature, including a homeopathic notion that "like cures like." Well into the seventeenth century, alchemical, hermetical, astrological, and other pre-scientific beliefs continued to exert, even on the minds of distinguished scientists, a discernible influence.

Concerned with the need to believe, in an age of incipient doubt, theatre audiences often witnessed in tragedies such struggles to sustain belief: Hamlet has a need to trust the Ghost; Lear has a wracked concern for heavenly powers; and Othello's desperate necessity to preserve his belief in Desdemona--"when I love thee not, / Chaos is come again" (3.3.92-3). For Othello and Lear, belief is sanity.

Common words in the dramatist's language often reflected beliefs or theological concepts that we today are not sensitive to. For instance, the word "nothing" in Hamlet's exchange with Ophelia at the play-within-the-play has bawdy insinuations because it represents "O":

Ham. That's a faire thought to lie between Maids' legs.

Oph. What is my lord?

Ham. Nothing. (3.2.114-16)

It has as well a profounder sense: in theological terms creation was constructed out of nothing, and this view held by Christians was in opposition to the view of creation held by pagans. It may have seemed therefore almost blasphemous to the audience when Shakespeare's Lear says "Nothing can be made out of nothing" (1.4.132) because in Christian belief so much had indeed been made by God out of nothing. By the same token it may be that Shakespeare's title Much Ado About Nothing is rather more pointed than modern audiences think--all created things consist essentially of nothing, which is why man is so foolish to hanker after material things.

Theologically, in the later sixteenth century, divine providence seemed increasingly to be questioned, or at least to be regarded as more bafflingly inscrutable. The medieval sense of security was in a process of transformation. Those changes coincided with such circumstances as the Renaissance revival of Epicureanism, which stressed the indifference of the powers above to man's concerns. The Reformation too reflected the new materialist traditions, especially Calvinism, which argued an incomprehensible and unappeasable God, whose judgments of election and reprobation had already, beyond human intervention, been determined. In place of a special personal power, was re-emphasized in Machiavelli (1469-1527) and other Renaissance writers.

Such changes in the relations of man and his Deity inevitably provided an altered climate for tragedy, wherein both divine justice (as in King Lear) and meaningful action (as in Hamlet) seemed equally unattainable. Lear appears to question the forces above man's life, and Hamlet the powers beyond his death. Hamlet's task is further complicated, for example, by his meaningless quest for action--from a Reformation standpoint—of works toward salvation. The path to salvation, of great concern to most Elizabethans, was not through works or merit but by inscrutable divine election. The Reformation's rejection of Purgatory made Hamlet's task thus all the more difficult.

Alienated from the objective structure of the traditional Church, as well as form release of the confessional, post-Reformation man, with burdened and isolated conscience, turned his guilt inward.

The Renaissance epistemological crisis emphasized the notion of the relativity of perception, recalling the appearance-versus-reality motif recurrent through Renaissance drama.

The Renaissance dramatist's work marks a transition between absolute natural law bestowed by God, and relativistic natural law, recognized by man. So too, many plays, like Jonson's The Alchemist, condemningly explore with specific monetary allusion the new acquisitive impulse.

For Machiavelli and Machiavellianism, which had great influence on Renaissance England, worldly politics were shaped not by the City of God but by the will, desire, cunning, virtÚ, and the energy of man.

In general, we speak of Elizabethan optimism giving way to Jacobean pessimism: John Donne expressed a lament for the new philosophy "which casts all in doubt"; its apostles were Galileo, Bacon, Montage, and Machiavelli.

Toward the end of the century, in literary tastes satire was the fashion, not the rage. Tragicomedy flourished. The history plays were given impetus from the defeat over the Spanish Armada (1588), a taste that lasted until about the end of the century. In the dramatists' plays, that energy is given physical expression by the gymnastic feats performed in the plays: scaling walls, the firing of canons, actors appearing on the "walls," etc.

These dramatists are indebted to a classical tradition for rhetoric, dramatic form, and decorum—there is an emphasis on the marital bond and on the need for public order in many of the Elizabethan plays.

The general temper of the Jacobean decade was satiric and critical. Roles now frequently inverted traditional ones. As a social ritual, the Jacobean court masque replaced the Elizabethan history play. Celebrating unity and concord, but designed for the few rather than the many, it depended on those assumptions of order and degree which, whatever their philosophic validity, were no longer socially at the center.

The old medieval stage of Place-and-scaffolds, still in use in Scotland early

in the sixteenth century, had fallen into disuse; the kind of temporary stage

that was dominant in England about 1575 was the booth stage of the marketplace—a

small rectangular stage mounted on trestles or barrels and "open" in

the sense of being surrounded by spectators on three sides.

The stage proper of the booth stage generally measured from 15 to 25 ft. in width and from 10 to 15 ft. in depth; its height above the ground averaged a bout 5 ft. 6 in., with extremes ranging as low as 4 ft. and as high as 8 ft.; and it was backed by a cloth-covered booth, usually open at the top, which served as a tiring-house.

About 1575 there were two kinds of building in England, both designed for functions other than the acting of plays, which were adapted by the players as temporary outdoor playhouses: the animal-baiting ring or "game house" (beargarden or bull ring), examples of which are recorded in pictorial and other records as standing on the south bank of the Thames opposite the City of London in the 1560s; and the inn, rather the "great inn," which, like the animal-baiting house, constituted a "natural" playhouse—presumably a booth stage was set up against a wall at one side of the yard, with the audience standing in the yard surrounding the stage on three sides. The price of admission was gathered at the moment of each spectator's entrance to the "house."

It is customary to distinguish two major classes of permanent Elizabethan playhouse, "public" and "private." The terms are somewhat cloudy, but what they designate is clear enough. In general, the public playhouses were large, "round," outdoor theatres, whereas the private playhouses were smaller, rectangular, indoor theatres. (An exception among public playhouses in the matter of roundness was the square Fortune of 1600.) The maximum capacity of a typical public playhouse (the Swan or the Globe) was about 3,000 spectators; that of a typical private playhouse (the Second Blackfriars or the Phoenix), about 700 spectators.

At the public playhouses a majority of spectators stood in the yard for a penny (the remainder sitting in galleries and boxes for two pence or more), whereas at the private playhouses all spectators were seated (in pit, galleries, and boxes) and paid sixpence or more. Originally the private playhouses were used exclusively by Boys' companies, but this distinction disappeared about 1609 when the King's Men began using the Blackfriars in winter as well as the Globe in summer.

Originally the private playhouses were found only within the City of London (the Paul's Playhouse, the First and Second Blackfriars), the public playhouses only in the suburbs (the Theatre, the Curtain, the Rose, the Globe, the Fortune, the Red Bull); but this distinction disappeared about 1606 with the opening of the Whitefriars Playhouse to the west of Ludgate.

Public-theatre audiences, though socially heterogeneous, were drawn mainly from the lower classes--a situation that has caused modern scholars to refer to the public-theatre audiences as "popular"; whereas private-theatre audiences tended to be better educated and of higher social rank—"select" is the word most usually opposed to "popular" in this respect.

James Burbage, father to the famous actor Richard Burbage of Shakespeare's company, built the first permanent theatre in London, the Theatre, in 1576. He probably merely adapted the form of the baiting-house to theatrical needs. To do so he built a large round structure very much like a baiting-house but with five major innovations in the received form. First, he paved the ring with brick or stone, thus paving the pit into a "yard."

Second, Burbage erected a stage in the yard—his model was the booth stage of the marketplace, larger than used before with posts rather than trestles.

Third, he erected a permanent tiring-house in place of the booth. Here his chief model was the screens passage of the Tudor domestic hall, modified to withstand the weather by the insertion of doors in the doorways. Presumably the tiring-house, as a permanent structure, was inset into the frame of the playhouse rather than, as in the older temporary situation of the booth stage, set up against the frame of a baiting-house. The gallery over the tiring-house (presumably divided into boxes) was capable of serving variously as a "Lord's room" for privileged or high-paying spectators, as a music-room, and as a station for the occasional performance of action "above."

Fourth, Burbage built a "cover" over the rear part of the stage, supported by posts rising from the yard and surmounted by a "hut."

And fifth, Burbage added a third gallery to the frame. The theory of origin and development suggested in the preceding accords with our chief pictorial source of information about the Elizabethan stage, the "De Wit" drawing of the interior of the Swan Playhouse (c. 1596).

It seems likely that most of the round public playhouses--specifically, the Theatre (1576), the Swan (1595), the First Globe (1599), the Hope (1614), and the Second Globe (1614)—were of about the same size.

The Second Blackfriars Playhouse of 1596 was designed by James Burbage, and he built his playhouse in the upper-story Parliament Chamber of the Upper Frater of the priory. The Parliament Chamber measured 100 ft. in length, but for the playhouse Burbage used only two-thirds of this length. The room in question, after the removal of partitions dividing it into apartments, measured 46 ft. in width and 66 ft. in length. The stage probably measured 29 ft. in width and 18 ft. 6 in. in depth.

In the private-theatres act-intervals and inter-act music were customary from the beginning. A music-room was at first lacking in the public playhouses, since public-theatre performances did not originally employ act-intervals and inter-act music. About 1609, however, after the King's men had begun performing at the Blackfriars as well as at the Globe, the custom of inter-act music seems to have spread from the private to the public playhouses, and with it apparently came the custom of using one of the tiring-house boxes over the stage as a music-room.

The drama was conventional, not realistic: poetry was the most obvious convention, others included asides, soliloquies, boys playing the roles of women (femininity is suggestive of the differences of mind and behavior between men and women in Shakespeare—yet, unlike the Victorians' myth that the boys were not involved in sexual situations, they clearly were) battles (with but three or four participants), the daylight convention (many scenes are set at night, though the plays took place in mid-afternoon under the sky), a convention of time (the clock and calendar are used only at the dramatist's discretion), the convention of "eavesdropping" (many characters overhear others, which the audience is privy to but the overheard characters are not), and movement from place to place as suggested by the script and the audience's imagination. Exits were strong, and when everyone departed the stage, a change of scene was indicated. There was relatively little scenery, and costumes—for which companies paid a great deal of money--supplied the color and pageantry.

There was often dancing before and after the play—at times, during. Jigs were often given at the end of performances by the clowns: not mere dances, they were comprised of songs and bawdy knockabout farces filled with commentaries on current events. After 1600, they fell into derision and contempt and were only performed at theatres such as the Red Bull, which catered to an audience appreciative of the lowest humor and most violent action.

The clowns were the great headliners of the stage prior to the great tragedians of the late 1580s, such as Ned Alleyn. Still, every company had a top clown along with the tragedian—Shakespeare’s company was no exception: Will Kempe was the clown until forced out of the company in 1599, to be replaced by another famous clown, Robin Armin.

The Repertory system was demanding—besides playing six days a week, a company would be in continual rehearsal in order to add new plays and to refresh old ones in their schedule. A player would probably learn a new role every week, with thirty to forty roles in his head. Over a period of three years, a tragedian such as Edward Alleyn, lead player for the Admiral's Men, would learn not only fifty new parts but retain twenty or more old ones as well over a three-year period.

1559: Licensing of plays enacted: companies such as the Earl of Worcester, Warwick (primarily tumblers), Lord Strange's Men (also tumblers and acrobats)

1574: Earl of Leicester's Men patented

1583: Queen's Men established, taken from Leicester, Oxford, Sussex, Derby, and Henry Lord Hunsdon (all provincial, touring companies)

c. 1585: Second Lord Strange's Men

1585 Lord Admiral's

1592-93 (First) Earl of Pembroke's

1594 Chamberlain's Men (playing alternately with Admiral's at Newington Butts)

1597 (Second) Pembroke's

Shakespeare may have begun with Alleyn's company (Admiral's/Strange's conglomerate, in 1591, and then gone with Pembroke's, then Chamberlain's.

(Some lesser known companies: Earl of Hertford's, Lord Norris', Morley's)

Aristotle:

"A tragedy, then, is the imitation of an action that is serious and also, as having magnitude, complete in itself; in language with pleasurable accessories, each kind brought in separately in the parts of the work; in a dramatic, not in a narrative form; with incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish its catharsis of such emotions" (The Poetics, VI, 335-322 B.C.).

Chaucer:

when one falls "out of heigh degree / Into miserie, and endeth wrecchedly" (Prologue to "The Monk's Tale," 1387-1400).

Sidney:

it "opens the greatest wounds...that makes kings fear to be tyrants...and teaches the uncertainty of this world" (Apology, 1581-83).

There are many different kinds of tragedy: today, in fact, some schools of critical theory do not recognize the "idea" of tragedy—classical or otherwise—as a generic distinction for "knowing" a work, emphasizing instead, as Feminist Theory does, social structures and relationships as the principle forces that move and inform the work. Shakespeare was influenced by Senecan tragedy foremost, perhaps somewhat by the Greeks—but to a small extent—and by the native tradition.

Greeks: tragedy did not have to end in death; the worst offense for man was to call attention to himself (hubris: pride); no promise of an afterlife; oracle at Solon: "better for man never to have been born--next best, to die young."

The soul had to be in balance; when it was not madness resulted, leading to tragedy:

Nous

Will / Understanding

Appetite

This formula held even to Shakespeare's day, where his tragic heroes always have some imbalance (appetite overcoming "nous," etc.). But whereas the Greeks cared nothing for intention, only action, Shakespeare is very concerned with intention.

Romans: influenced by Greeks; very pertinent to contemporary events, especially the violence and contrariness of emperors; imagery and subject were violent and hell-ridden; themes were Greek, but combined with stoicism, which leant a detachment and world of the high place. Were they declaimed rather than staged? Images of hell combined with cool detachment and especially restraint; thus the messenger of horror rather than the actual scenes on stage.

Middle Ages: tragedy loses attachment to performance; narratives that end unhappily and offer warnings; all within a system of God's plan.

Renaissance: imitation of classical authority, Seneca, but because of Christian thinking Seneca is blended with a native tradition (it is argued that there is no native tradition in English tragedy; yet the didacticism, symbolism for contemporary events, and inherent conflicts within the "Tudor Myth" all inform many tragedies, yielding a particular form of English tragedy that is not confined to genre but more homogeneous), meaning moral purpose, a "warning" for the present, examples in history.

Aristotle's "unities," as recognized by Castlevetro in Italy, are imitated by some. The genre is defined largely by those who write in it—tragicomedy (John Fletcher, The Faithful Sheperdess, 1610, defines term) is a good illustration of how far it could be taken or defined. Shakespeare's different concepts of tragedy, for instance, include Titus (Senecan, hereditary curse), Romeo (time as messenger of fate, and innocence of trag. victims), later tragedies ("flawed" heroes, bad choices, cause and effect).

Senecan tragedy: (Seneca the Younger, 4 B.C.-65 A.D.) "Closet Dramas" or "Speakings" that were not intended for performance, although the Renaissance writers were ignorant of this fact. Influenced by late-Greek drama of Euripides, and so in five acts. His Thyestes was the most popular among the Elizabethans and stressed the power of an hereditary curse.

Characterized by: theme of revenge; chorus who moralize but do not participate; "nuntius," or messenger, who reports violent events not visually represented; dramatic focus on emotional climax rather than episodic progression toward climax; 5 Act structure; ghost, often seeking revenge; stock characters; introspective, moralizing hero; emphasis on sensational and violent situations--incest, insanity, mutilation, suicide, etc., drawn from Greek drama; style characterized by bombast, rant, descriptions, soliloquies--a love of skillfully manipulated words; and finally, a villain who is possessed--there are no villains in Greek tragedy.

Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy (1585-87) set off a wave of imitations that set the standard for Elizabethan tragedy. It was the most popular play of the era.

Elizabethan Tragedy: offers a warning; more free will than Greek or Senecan tragedy; yet this is not consistent (cf. Romeo where circumstance is more powerful than action); beyond human control even when a character is "flawed"—cf. Macbeth, where a worse man would not need tempting and a better would not have yielded; he was ideally suited to the time, events, temptation.

Less concerned with genre—mixing of comedy and tragedy; often character centered rather than plot centered; progress or decline is measured vertically, either toward or away from God; always Christianity conscious (the dramatist's symbolism often draws heavily on Christian themes; even rejections—Faust—or classical models are heavily couched in Christian theme and symbolism); Shakespeare, for one, introduces the dramatic value of "doubt"—he doesn't pretend to know his characters thoroughly and doesn't attempt to answer all questions; in fact, he is deliberately ambiguous; cosmic tragedy that goes far beyond the central character (cosmic forces are seen as chance, such as the handkerchief in Shakespeare's Othello; action and reason are often the central conflicts.