| You'll

find a few representative illustrations of Shakespeare, his age, and the

London theatres at this site. For a more comprehensive view, I recommend

that you visit such sites as

http://www.itasmatteoricci.sinp.net/lascuola/didattica/Progetti/teatro/did/images.html,

or

http://www.luminarium.org/renlit/index.html,

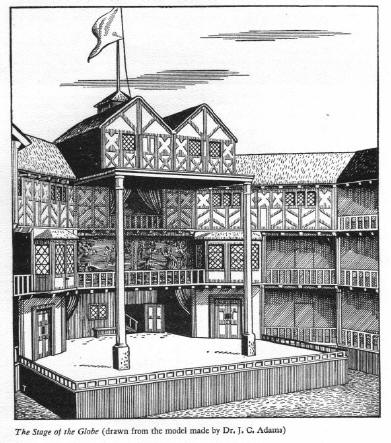

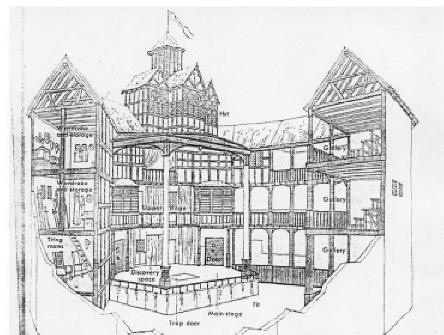

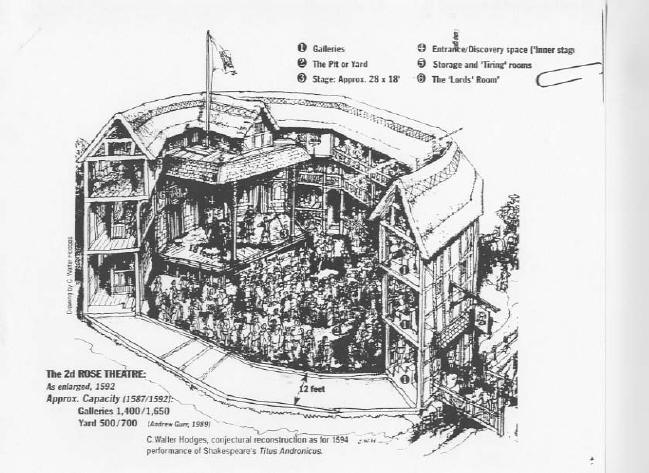

among the many sites available on Shakespeare and his age. The Globe Theatre The Second Rose Theatre The Swan Theatre The City of London in Shakespeare's Day Cut-away Rendering of the Globe Theatre Information on the primary distinctions of stage attributes: Conventions and Analogies

Globe Theatre (Adams)

deWitt drawing of the Swan Theatre

City of London in Shakespeare's Day

Cut-away view of the Globe Theatre (Adams)

Analogies and Conventions: Two important things remain to remember when studying Shakespeare and his art. First, the theatre was both conventional and analogical. "Conventional" means a shorthand form for reality, understood by audience and actor alike. That is, conventions represent a way to denote an idea, a physical condition, a quality that needs no exhaustive explanation or description (as is often the case in modern drama). For example, sighing conveys the idea of one being in love. The quality is call "adust," a thickening of the blood from the heat that passion generates upon the heart. Sighing serves to release that heat in order that we not die; this Romeo says "Ay me" at the first of play to signal to the audience that he is a lover. In addition, he probably leaned against a post supporting the balcony, crossed his legs and arms, and conveyed a look of exhaustion or the inability to sustain an upright position without the benefit of something to lean against. Other forms of conventions include the soliloquy (speaking one's thoughts aloud while alone on stage), the aside (makeing a statement that more than a thousand people can hear, but which the character it describes or remarks upon cannot hear it, even though he may only be five feet away), poetry (the people in Shakespeare's day did not say things such things as "but soft / what light through yonder window breaks...), or boys playing the parts of women (the English believed it to be unseemly for women to play upon the stage. The French might do such things, but then consider that the French....) Conventions, therefore, serve to make clear shortcuts in the game of playing. Second, the stage was analogical; that is, its physical structure made an analogy of God's universe within a microcosm called the theatre. The upper-most part of the playhouse (the hut) was also called "the Heavens," where machinery might be hidden from the sight of the audience--sound effects such as bowling balls rolling down wooden troughs in order to sound like thunder, or pulleys and wires for hefting angels or supernatural beings, etc. In the middle of the stage was a trap door that opened to "Hell"--the space below the stage, used for storage but for entrances for devils and witches as well--which left the middle area, the stage itself, to represent the "Earth," or mankind's life in its journey between Heaven and Hell. The analogical mode of the stage is perhaps best expressed by Jacques' speech in As You Like It:

All the world's a stage, And all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances, And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages. At first the infant, Mewling and puking in the nurse's arms. Then, the whining school-boy with his satchel Unwillingly to school. And then the lover, Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad Made to his mistress' eyebrow. Then, a soldier, Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard, Jealous in hounour, sudden, and quick in quarrel, Seeking the bubble reputation Even in the cannon's mouth. And then, the justice, In fair round belly, with good capon lin'd, With eyes severe, and beard of formal cut, Full of wise saws, and modern instances, And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts Into the lean and slipper'd pantaloon, With spectacles on nose, and pouch on side, His youthful hose well sav'd, a world too wide For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice, Turning again toward childish treble, pipes And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all, That ends this strange eventful history, Is second childishness and mere oblivion, Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

(As You Like It, 2.7.139-166)

Thus one who stands before the stage in the pit with the "penny public," or sits in the more expensive seats, beneath shelter and safe from the bad weather, looks upon the stage and sees the microcosm of God's universe: the Heavens above, Hell below, and the middle ground--the stage proper--as Earth, upon which mankind has its entrances and exits.

The Spanish drama of Calderat about the same as Shakespeare in England, took this a step further and often had a character on stage--the stage manager--who represented God. All players are judged against their roles given in life, how well they play, how well they know their lines and use their props, and are evaluated at play's end by the manager. Such a character was, at times, in full view of the audience, who understood his symbolic role.

Where a character stands upon the stage, and especially where characters enter and exit, has analogical meaning: an analogy occurs between the Theatrum Mundi, "World as Theatre," and the lives we lead. The Puritans may have hated the theatre (which they saw as a "lie," an illusion that misrepresented life and God's realities, to say nothing of the injunction against men wearing women's clothing in Deuteronomy), but the stage of Shakespeare's day reminded people of the "Great Chain of Being," the order of God's universe. Much like a ladder, the Chain had God at the top and Satan at the bottom. Everything on the ladder is fixed and has a purpose, whether humanity, animals, plants, rocks, or anything within God's creation. And balance always exists: If a certain number of angels and archangels appear at the top, a similar number and order will exist at the bottom. Evil exists only for the purpose of distorting good: Communion, therefore, has it's mirror in the Black Mass of Satan; the next in line to Satan sits at his left hand, as to oppose Jesus on the right hand of God.

Only humanity can move on the chain; all else is fixed. Humans, created a little lower than the angels, may fall down the chain until closer to Satan, or they may serve God and ascend to their rightful place a little lower than the angels. We know about the characters in Shakespeare's plays by their language, but also by their positioning upon the stage. Unfortunately, since his plays were not regarded as literature and were printed only to counter other companies from stealing their work and representing it as their own, stage directions rarely exist; nor do we know where characters were positioned upon the stage. But the answers to those questions remain paramount in understanding how we view the characters and their actions. For example, when the Ghost first appears in Hamlet, from where does he come? Does he arise from the trap door from Hell? Does he first appear upon the balcony area (closer to Heaven)? If the latter, we should presume that the Ghost indeed comes from God for heavenly purpose; but should he arise from the trap door, from Hell, we may ask ourselves whether or not this Ghost desires, as Hamlet speculates, to snare his soul as a representative from Hell.

Notice too that language combined with physical positioning tells us much about the characters. After the Capulet party, Romeo climbs a wall to avoid his friends, only to find himself in the garden below Juliet's room. Here we have Romeo on Earth, and Juliet closer to the Heavens. Romeo's language remains full of images of stars, moon, heavens, etc.; Juliet's language, on the other hand, appears more grounded, focusing on hands and eyes, etc. Therefore, we feel that Juliet is more "grounded" in her feelings and, given her physical position, more spiritual as a result. Romeo speaks of heavenly images, remains on the "Earth," and thus seems less grounded and less mature than Juliet. And so Romeo changes more in the play than does she, because he has more need/room to do so.

It may have been that the actors in these companies read the scripts and, when rehearsals began, knew where to move and where to stand due to their understanding of their characters and the words spoken. A director (which they called an "Instructor") would still be necessary; but these acting professionals used the physical space of the stage and the lines given their characters to understand where to stand, when to move, and what their relationship was to the stage world (Theatrum mundi). When one adds conventions to the player's understanding, it suggests to us that Elizabethan/Jacobean actors used their knowledge of the profession to quickly move through rehearsals and the performance process.

lays didn't run as long as we might suppose--perhaps only two or three times a week for a month (or occasion longer) or less--before they moved on to other material. Remember, Shakespeare wrote 37 plays, but the company of which he was a member, as both dramatist and actor (apparently, he specialized in the portrayal of older men), might need anywhere from 35 to 50 plays a year. That means that Richard Burbage, lead tragedian for the Chamberlain's Men and later King's Men (when James the IV of Scotland came down to England at the death of Elizabeth, he assumed the title of James I of England, becoming the patron of Shakespeare's acting company that heretofore had been patronized by the Lord Chamberlain--a true honor) had to keep nearly 50 roles in his head in any given year. This tells us something about the prodigious memories of these players, as well as their need for conventions and positioning analogies in order to help the quick learning of roles.

The physical demands of that work (sword fighting, dancing, tumbling, and oratorical excellence) must have been outstanding. As Hamlet says to the visiting players to Elsinor, "give us a taste of your quality" (2.2405)--the "quality" of which he speaks is, in a word, the player's "art."

The 2nd Rose Theatre, 1592

|

|

|