The

stage proper of the booth stage generally measured from 15 to 25 ft. in width

and from 10 to 15 ft. in depth; its height above the ground averaged a bout 5

ft. 6 in., with extremes ranging as low as 4 ft. and as high as 8 ft.; and it

was backed by a cloth-covered booth, usually open at the top, which served as

a tiring-house.

About 1575 there were two kinds of building in England, both designed for functions other than the acting of plays, which were adapted by the players as temporary outdoor playhouses: the

animal-baiting ring or "game house" (beargarden or bull ring), examples of which are recorded in pictorial and other records as standing on the south bank of the Thames opposite the City of London in the 1560s; and the inn, rather the "great inn,"

which, like the animal-baiting house, constituted a "natural" playhouse—presumably a booth stage was set up against a wall at one side of the yard, with the audience standing in the yard surrounding the stage on three sides. The price of

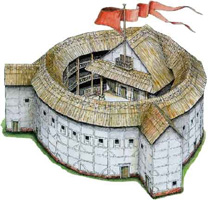

It is customary to distinguish two major classes of permanent Elizabethan playhouse, "public" and "private." The terms are somewhat

cloudy, but what they designate is clear enough. In general, the public playhouses were large, "round," outdoor theatres, whereas the private playhouses were smaller, rectangular, indoor theatres. (An exception among public playhouses in the matter of roundness was the square Fortune of 1600.) The maximum capacity of a typical public playhouse (the Swan or the Globe) was about 3,000 spectators; that of a typical private playhouse (the Second Blackfriars or the Phoenix), about 700 spectators.

At the public playhouses a majority of spectators stood in the yard for a penny (the remainder sitting in galleries and boxes for two pence or more), whereas at the private playhouses all

spectators were seated (in pit, galleries, and boxes) and paid sixpence or more. Originally, the boys’ companies exclusively used the private playhouses, but this distinction disappeared about 1609 when the King's Men began using the Blackfriars in winter as well as

the Globe in summer.

Originally the private playhouses

were found only within the City of London (the Paul's Playhouse, the First and Second Blackfriars), the public playhouses only in the suburbs (the Theatre, the

Curtain, the Rose, the Globe, the Fortune, the Red Bull); but this distinction disappeared about 1606 with the opening of the Whitefriars Playhouse to the west of Ludgate.

were found only within the City of London (the Paul's Playhouse, the First and Second Blackfriars), the public playhouses only in the suburbs (the Theatre, the

Curtain, the Rose, the Globe, the Fortune, the Red Bull); but this distinction disappeared about 1606 with the opening of the Whitefriars Playhouse to the west of Ludgate.

Public-theatre audiences, though socially heterogeneous, were drawn mainly from the lower classes--a situation that has caused modern scholars to refer to the public-theatre audiences as

"popular"; whereas private-theatre audiences tended to be better educated and of higher social rank—"select" is the word most usually opposed to "popular" in this respect.

John Brayne built the Red Lion in 1567 outside the city walls of London in an area called the “Liberties,” thus free from the jurisdiction of the city of London, which was most certainly the first open-air theatre used primarily

for playing, as opposed to the rooms or courtyards that the various inns about London provided for playing. While some argument exists as to whether the Red Lion was the first building used exclusively for playing (did it

also serve a function much like the inns about the roads leading into and out of London, or serve for other sport, such as bear-baiting?), nonetheless Brayne had playing in mind as its chief activity. In any event, it must

have been successful, because Brayne and his brother-in-law, James Burbage, built the Theatre in 1576, a playhouse used exclusively for playing. It too found a home outside the jurisdiction of the Lord Mayor and the city

councilmen, and was quickly followed by other entrepreneurs who built their own playhouses, such as the Curtain, close by the Theatre, where Romeo and Juliet and other plays of Shakespeare would find an audience.

Thus,

in Shakespeare’s day, there existed many playing venues: some of which recalled

the simple stages and single curtains used by small, traveling companies who

performed at fairs, or fields, or anywhere they could gather an audience; the

inns, which were constant hubs of activity and provided a yard and balcony

above; the great halls found in the manors about England, which provided raised

stages and upper rooms; the halls at the Inns of Courts in London, where young

men went to study law and which provided shelter, as did the great halls in

manor houses, against inclement weather. So, too, the actors and theatre entrepreneurs of England, who had attended school where classical training included plays, staged

in the great halls of the Merchant Taylors School, Oxford, or Cambridge. In sum, when Shakespeare was born, there were numerous venues for playing that provided the traditions from which the permanent theatres of his day

drew; as both player and writer, Shakespeare inherited the amalgam of what worked best and was most desirable, from both the player’s and the audience’s points of view.

Thus,

in Shakespeare’s day, there existed many playing venues: some of which recalled

the simple stages and single curtains used by small, traveling companies who

performed at fairs, or fields, or anywhere they could gather an audience; the

inns, which were constant hubs of activity and provided a yard and balcony

above; the great halls found in the manors about England, which provided raised

stages and upper rooms; the halls at the Inns of Courts in London, where young

men went to study law and which provided shelter, as did the great halls in

manor houses, against inclement weather. So, too, the actors and theatre entrepreneurs of England, who had attended school where classical training included plays, staged

in the great halls of the Merchant Taylors School, Oxford, or Cambridge. In sum, when Shakespeare was born, there were numerous venues for playing that provided the traditions from which the permanent theatres of his day

drew; as both player and writer, Shakespeare inherited the amalgam of what worked best and was most desirable, from both the player’s and the audience’s points of view.

James Burbage, brother-in-law and partner to John Brayne, was father to the famous actor Richard Burbage of Shakespeare's company; it was he who built the first permanent theatre in London, the

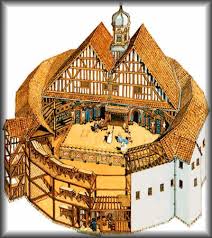

Theatre, in 1576, probably adapting the form of the baiting-house to theatrical needs, but knowing as well how well the inn yards served players and viewers. He built a large round structure very much like a baiting-house but

with five major innovations in the received form. First, he paved the ring with brick or stone, thus paving the pit into a "yard."

Second, Burbage erected a stage in the yard—his model was the booth stage of the marketplace, larger than used before with posts rather than trestles.

Third, he erected a permanent tiring-house in place of the booth. Here his chief model was the screens

passage of the Tudor domestic hall, modified to withstand the weather by the insertion of doors in the doorways. Presumably, the tiring-house, as a permanent structure, was inset into the frame of the playhouse rather than,

as in the older temporary situation of the booth stage, set up against the frame of a baiting-house. The gallery over the tiring-house (presumably divided into boxes) was capable of serving variously as a "Lord's

room" for privileged or high-paying spectators, as a music-room, and as a station for the occasional performance of action "above."

Fourth, Burbage built a "cover" over the rear part of the stage, supported by posts rising from the yard and surmounted by a "hut."

And fifth, Burbage added a third gallery to the frame. The theory of origin and development suggested in the preceding accords with our chief pictorial source of information about the Elizabethan stage, the "De Wit" drawing of the interior of the Swan Playhouse (c. 1596).

It seems likely that most of the round public playhouses--specifically, the Theatre (1576), the Swan (1595), the First Globe (1599), the Hope (1614), and the Second Globe (1614)—were of about the

same size.

James Burbage designed the Second Blackfriars Playhouse of 1596, and he built his playhouse in the upper-story

Parliament Chamber of the Upper Frater of the priory. The Parliament Chamber measured 100 ft. in length, but for the playhouse Burbage used only two-thirds of this length. The room in question, after the removal of partitions

dividing it into apartments, measured 46 ft. in width and 66 ft. in length. The stage probably measured 29 ft. in width and 18 ft. 6 in. in depth.

In the private-theatres act-intervals and inter-act music were customary from the beginning. A music-room was at first lacking in the public playhouses,

since public-theatre performances did not originally employ act-intervals and inter-act music. About 1609, however, after the King's men had begun performing at the Blackfriars as well as at the Globe, the custom of inter-act music seems to have spread from the private to the public playhouses, and with it apparently came the custom of using

one of the tiring-house boxes over the stage as a music-room.

The drama was conventional, not realistic: poetry was the most obvious convention, others included asides, soliloquies, boys playing the roles of women (femininity is suggestive of the differences

of mind and behavior between men and women in Shakespeare—yet, unlike the Victorians' myth that the boys were not involved in sexual situations, they clearly were) battles (with but three or four participants), the daylight convention (many scenes are set at night,

though the plays took place in mid-afternoon under the sky), a convention of time (the clock and calendar are used only at the dramatist's discretion), the convention of "eavesdropping" (many characters overhear others, which the audience is privy to but the

overheard characters are not), and movement from place to place as suggested by the script and the audience's imagination. Exits were strong, and when everyone departed the stage, a change of scene was indicated. There was relatively little scenery, and costumes—for

which companies paid a great deal of money--supplied the color and pageantry.

There was often dancing before and after the play—at times, during. Jigs were often given at the end of performances by the clowns: not mere dances,

they were comprised of songs and bawdy knockabout farces filled with commentaries on current events. After 1600, they fell into derision and contempt and were only performed at theatres such as the Red Bull, which catered to

an audience appreciative of the lowest humor and most violent action.

The clowns were the great headliners of the stage before the great tragedians of the late 1580s, such as Ned Alleyn. Still, every company had a top

clown along with the tragedian—Shakespeare’s company was no exception: Will Kempe was the clown until forced out of the company in 1599, to be replaced by another famous clown, Robin Armin.

The Repertory system was demanding—besides playing six days a week, a company would be in continual rehearsal in order to add new plays and to refresh old ones in their schedule. A player would probably learn a new role every week, with thirty to forty roles in his head. Over a period of three years, a tragedian such as Edward Alleyn, lead player for the

Admiral's Men, would learn not only fifty new parts but retain twenty or more old ones as well over a three-year period.

The Repertory system was demanding—besides playing six days a week, a company would be in continual rehearsal in order to add new plays and to refresh old ones in their schedule. A player would probably learn a new role every week, with thirty to forty roles in his head. Over a period of three years, a tragedian such as Edward Alleyn, lead player for the

Admiral's Men, would learn not only fifty new parts but retain twenty or more old ones as well over a three-year period.

All the major support beams were marked by Street and his men in order to reconstruct the basis for the new Globe enterprise, which came about six months later. With three galleries, a

tiring house, spacious yard for the penny public, it was soon turned into the most sumptuous public playhouse in London. As for viewers, the penny public “pit” would hold approximately 1000 standing patrons, while just as

many, and perhaps up to 1500, could watch from the three levels.

Eight people shared in the expenses of constructing the new playhouse, and thus shared in its profits: the sons of James Burbage, Richard and Cuthbert, each owned 25%, while five actors, Augustine Phillips, Thomas Pope, John Heminges,

Will Kempe, and William Shakespeare, each owned 10%. Cuthbert alone was not an actor; thus, 6 players constituted the owners, paying themselves, the rent on their building, and all other costs from their profits from playing

and their shares in the venture. The other, less obvious advantage, perhaps, is that in his capacity as dramatist Shakespeare could write specifically for these men and for this space, constructing his plays with a

familiarity that few enjoyed.

In 1613, during a performance of Henry VIII, the thatch roof of the Globe theatre caught fire from the sparks of a fired canon. A second Globe appeared on the foundations of the

first.

1559: Licensing of plays enacted: companies such as the Earl of Worcester, Warwick (primarily tumblers), Lord Strange's Men (also tumblers and acrobats)

1574: Earl of Leicester's Men patented

1583: Queen's Men established, taken from Leicester, Oxford, Sussex, Derby, and Henry Lord Hunsdon (all provincial, touring companies)

c. 1585: Second Lord Strange's Men

1585 Lord Admiral's

1592-93 (First) Earl of Pembroke's

1594 Chamberlain's Men (playing alternately with Admiral's at Newington Butts)

1597 (Second) Pembroke's

Shakespeare may have begun with Alleyn's company (Admiral's/Strange's conglomerate, in 1591, and then gone with Pembroke's, then Chamberlain's.

(Some lesser known companies: Earl of Hertford's, Lord Norris', Morley's)

Need more information on publishing practices, Shakespeare's language, the stage, etc.? Myriad Shakespeare sites exist on the web; one of the newest, least intimidating may be found at http://www.ciconline.org/bdp1/.