Jacob Narratives Summary

... and Moses Summary

You’ll notice that I don’t separate this final summary “lecture” by differentiating the many narratives that concern Jacob; and many indeed exist that students of the Hebrew Scriptures would find of interest: the birth, the duplicity by which he wins his brother’s birthright, the actual moment when Jacob, with the help of his mother, steals the birthright, Jacob’s return to the land of his birth and the first of many dreams to be found in the Hebrew narratives, the story of his sons, the rape of his daughter, Dinah, and finally that which most links him with the Hebrew people through his youngest son, Joseph. While all of these narratives are of interest, it becomes necessary to focus on but a few episodes taken from several in order to appreciate their value for the story of the Hebrew nation.

Jacob represents the promise of

Abraham’s seed through his son Isaac, whom God used to test Abraham and the

future of a people. It may surprise

many students of the Bible to learn that most scholars tend to focus more on

Jacob as the most important figure in the myths, legends, stories, promises,

and, finally, epic of a nation.

We may pause here briefly in order to note that what differentiates the genre of epic from other literary forms is that an epic tells

the story of how a people came to be, and, in so doing, focuses upon a single

individual and how he figures in and becomes the champion of that struggle.

Narratives swell in proportion to both the importance of and the years from

which the person is remembered.

In other words, those earliest figures remain safely distanced by time

and memory so that it becomes difficult to determine truth from fiction; but

then, it matters not if the person represents the best impulses or ideas of a

nation—he or she may become the metaphor for an entire people.

differentiates the genre of epic from other literary forms is that an epic tells

the story of how a people came to be, and, in so doing, focuses upon a single

individual and how he figures in and becomes the champion of that struggle.

Narratives swell in proportion to both the importance of and the years from

which the person is remembered.

In other words, those earliest figures remain safely distanced by time

and memory so that it becomes difficult to determine truth from fiction; but

then, it matters not if the person represents the best impulses or ideas of a

nation—he or she may become the metaphor for an entire people.

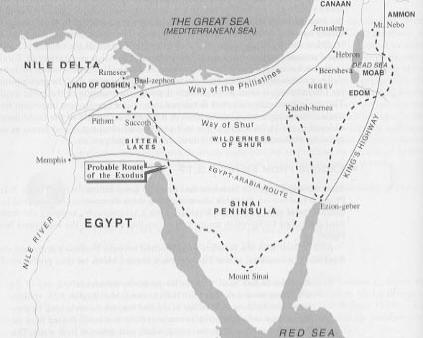

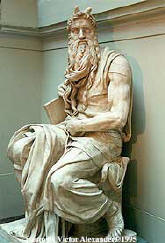

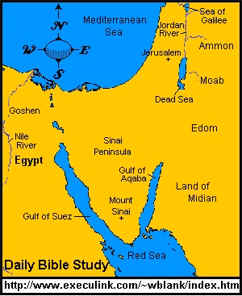

Most would ascribe this function to Moses. Indeed, as we shall see, Moses fulfills all requirements and then some, so to speak, in that he has a personal encounter with God, literally leads his people out of their bondage and past, and formulates all that becomes the nation, which establishes its place within the “promised land,” that place that Abraham first called home after being called away from his home in the Mesopotamian valley. The Hebrew nations had three “invasions” or callings to the land of Canaan, which was originally never theirs: first, we have the call to Abraham to leave his home in Ur and to go to a land that God would show him: Canaan. From the heights of Hebron he watched the smoke arise on the horizon signaling the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, the fertile land that his nephew chose in order to avoid conflict between the herdsmen and followers of his uncle and his own. By tradition, he attempted to sacrifice his own son, Isaac, in obedience to God on the “mountain” that would one day be the home of Solomon’s Temple. The seed of Abraham would one day return from their adopted home and later site of slavery in Egypt to reclaim their land from the inhabitants of Canaan, as the spies from Moses’ camp across the Jordan found their way into Jericho, one of the most ancient of cities, to reclaim through war their promised home. It was then that these people would find their way back to the land where father Abraham had been lead by God, in order to reorganize and to reconstruct their past and to correct their failures following captivity by the hands of the Babylonians.

Most students of the Bible would quickly point to Moses as the epic figure, the epitome of all that represents a people, a name attributed to the Torah, the first five books of Scripture, in order to lend the name of their most famous son to their retelling of nation-building. But Moses was a descendant of one of Jacob’s sons; his own brother Aaron becomes priest, and all those of the tribe of Levi would become more respected in terms of authority and spokesmen for God. Indeed, Moses, who had his own failings, as all great Biblical heroes do, never saw to fruition the dream of that land promised by God. So too, I would argue, Jacob fulfills the trope of the most interesting and oldest of the biblical writers, so named as “J” due to his insistence upon referring to God as YWYH, which German biblical scholars, those who advanced the “higher criticism” predominantly in the 19th century, named the “Yahwist” writer, due to the pronunciation of the name that stood for Jehovah, the unpronounceable name of the Hebrew’s highest god (a name that never appears in the Bible until the Middle Ages). Other differences exist as well as to the recognizable differences in this writer from the several others to be found in the Hebrew Scriptures: language differences, knowledge of events more pertinent to his time than to others, archaeological findings that confirm his era of writing, and stylistic differences in story-telling that surpass all possibilities that Moses on anyone else was merely writing a bit differently on any given day. In the LXX, the so-called Septuagint from tradition, those scholars of the Greek world writing from northern Africa several centuries prior to Christ, acknowledge the differences in authorship as they translate the Hebrew into the lingua franca of their day. The so-called Masoretic text, also known as the Leningrad manuscript, would once again, and largely based on the LXX, translate the Bible into Hebrew before the 11th century, BCE. They too acknowledged the recognizable differences in hands, in tone, in direction, in preference for what God’s word should be.

But the important difference for our

purposes lies in the Yahwist’s writer’s love affair with the trope, the

metaphor, of who and what Jacob was.

One would not be far wrong in saying that the writer looked ahead toward

Jacob as his most ambitious project and, in pouring everything into him, seemed

a bit exhausted or let down in much of what followed, even though it was made of

the stuff of magic, supernatural forces, human drama, and the confrontations of

the divine with the human in dictating what

a

people, not an individual, should learn from the exchange.

We saw in J’s earliest narrative that the head/heel trope would serve as

figure for the relationship of God to Man.

There was once a time that God came down to visit His creation, to walk about,

to look them over, to check in on their progress or lack thereof.

But bit-by-bit, Yahweh was not pleased with the exchange, with what He learned,

and slowly if inexorably Yahweh distanced Himself from humanity, so that soon

they had to “come up” to Him. And

not long thereafter, not only did they come up, but only the chosen from among

them was so permitted. By the time

we get to Moses talking with God on Sinai, much has changed, new covenants made,

new promises set forth having previously been broken.

When Moses loses his right to cross over into the Promised Land, it comes from a

misdeed that Yahweh would have previously either forgiven or clarified in direct

address. Not so now. Too

much investment went into the burning bush, the recorded moral laws, the

suffering of a people who demonstrated on every occasion that they were

indifferent to their God.

a

people, not an individual, should learn from the exchange.

We saw in J’s earliest narrative that the head/heel trope would serve as

figure for the relationship of God to Man.

There was once a time that God came down to visit His creation, to walk about,

to look them over, to check in on their progress or lack thereof.

But bit-by-bit, Yahweh was not pleased with the exchange, with what He learned,

and slowly if inexorably Yahweh distanced Himself from humanity, so that soon

they had to “come up” to Him. And

not long thereafter, not only did they come up, but only the chosen from among

them was so permitted. By the time

we get to Moses talking with God on Sinai, much has changed, new covenants made,

new promises set forth having previously been broken.

When Moses loses his right to cross over into the Promised Land, it comes from a

misdeed that Yahweh would have previously either forgiven or clarified in direct

address. Not so now. Too

much investment went into the burning bush, the recorded moral laws, the

suffering of a people who demonstrated on every occasion that they were

indifferent to their God.

J’s first use of the head/heel trope occurs with the Serpent’s chastisement and punishment in the Garden; thereafter, the trope stands for the distance between Yahweh and His creation, ever-growing, ever more distant, and finalized when what He spoke to Moses is kept in pieces within an ark, available only to the priests in the Holy of Holies, and never more in direct address. Now, spokesmen do His bidding; and, more often than not, to deaf ears, so that the admonition “Hear, O Israel!” becomes something of a familiar preamble to anything smacking of religion or shouted by the numerous, indefatigable strange men of the desert, who shout it out at Holy days.

Jacob is the realization of the trope: his very name means “heel” or sneak. In looking back, either as divine scribe or poetic interpreter of the past, the J writer finds Jacob to be the personification of the distance that still maintains God and humans as one, two in the same image. In looking at the stories of so-called Old Testament figures, can anyone doubt that God loves the rascal above all others? Why the imperfections of David, the failings of Moses, the duplicities of Jacob, the bargaining’s of Abraham, the singularity of Noah (who likes to imbibe), or the “hands-on” affection afforded the first couple? It seems, not to speak it too lightly, that Yahweh enjoys the imperfections. I’m inclined to believe that Midrash stories must fairly abound as to Yahweh’s boredom with the perfections of heaven. And here I would mention but one story to illustrate this point, in which Abraham becomes enlightened by the God who ordered his own son’s execution: He tells the patriarch that He ordered Abraham to “come up,” not to sacrifice his son Isaac. The comparison of verbs is strikingly similar: given that Abraham questions God about His order, Yahweh instructs him on a grammatical point: “Come up” to me, not “yield up” your son. Such reading would have made the J writer proud—of course, he may have known the difference already and so constructed the narrative to take full advantage.

But this goes to the heart of J’s

trope: Yahweh never comes down anymore; humanity must go up.

The covenant made to Noah was general, in that it affected all humanity, and not

the faithful servant in

particular.

However, the covenant given to Abraham some time later is more specific,

and it has to do with a particular person, and people, and demonstrates for the

first time that Yahweh chooses His people, rather than the people

electing their gods. In these

narratives, Yahweh still comes down, but does so in disguise.

Who can figure whether angels appear to Abraham at Mamre or Yahweh

Himself?

J says that it was Yaweh, then goes on to say that three strangers stand

before the patriarch. Abraham

instantly knows it’s his God.

Were they interchangeable, look alike, to whom did he direct his speech?

Would Christians, as an after-thought to this, interpret this to mean the

Trinity?

It’s difficult to know, but what we’re certain about is that the

Tanakh changes when it concerns the patriarch of Israel, Abraham.

Chapter 12 of Genesis separates primeval history from patriarchal history, with

a recognizable difference: “Yahweh said to Abram.”

This is direct, straightforward, and the first relief from the genealogies that

please so much and become necessary for the Priestly writer(s), who, given their

bent for law and exactitude, must reconstruct laws, family histories, and the

like, especially since they’re dealing with a nation after (or still within)

captivity at the hands of the Babylonians.

How much have they forgotten or been changed by five hundred years as enforced

expatriates?

particular.

However, the covenant given to Abraham some time later is more specific,

and it has to do with a particular person, and people, and demonstrates for the

first time that Yahweh chooses His people, rather than the people

electing their gods. In these

narratives, Yahweh still comes down, but does so in disguise.

Who can figure whether angels appear to Abraham at Mamre or Yahweh

Himself?

J says that it was Yaweh, then goes on to say that three strangers stand

before the patriarch. Abraham

instantly knows it’s his God.

Were they interchangeable, look alike, to whom did he direct his speech?

Would Christians, as an after-thought to this, interpret this to mean the

Trinity?

It’s difficult to know, but what we’re certain about is that the

Tanakh changes when it concerns the patriarch of Israel, Abraham.

Chapter 12 of Genesis separates primeval history from patriarchal history, with

a recognizable difference: “Yahweh said to Abram.”

This is direct, straightforward, and the first relief from the genealogies that

please so much and become necessary for the Priestly writer(s), who, given their

bent for law and exactitude, must reconstruct laws, family histories, and the

like, especially since they’re dealing with a nation after (or still within)

captivity at the hands of the Babylonians.

How much have they forgotten or been changed by five hundred years as enforced

expatriates?

Such narratives as Abraham’s claim in Egypt that Sarai is his sister are typical of the J writer: we’ll see it used again by a male looking for security in having married well or above himself. On closer inspection, it seems a useful if less than dignified device—I’m reminded here of Shakespeare’s use of the “bed trick” in Measure for Measure and All’s Well That Ends Well, though the time and cultural tolerances must be taken into consideration: both are judged harshly by today’s standards, even for storytelling. The more important point remains: Abraham continues in direct contact with Yahweh; even at ninety-nine years old, he receives a visit from Yahweh, who identifies Himself here as El Shaddai, “God of the Mountain,” which Albright attributes to the Akkadian, and which is often translated as “Almighty” (it is used here in early anticipation of its more common use in the Moses narratives, for obvious reasons, but this is a telling pre-figuring of another appellation for God: J has Yahweh and His chosen representatives speaking freely, and those individuals are people described in all the variations of human behavior, often less than heavenly).

Jacob gets a free ride into life by clutching his brother’s heel; thus, the sneak literally defines his own metaphor. His name, itself, designates who and what he is. He grows up second at a time and within circumstances that make the seconds of separation at birth life informing. The differences between the two, even as twins, remains enormous: one is hairy, given to hunting and things of the wild, while the other is smooth of skin, enjoys life within the tents, and remains his mother’s favorite, even as the father prefers the other. This comparison of the twins, much like the earlier narrative of Noah and his avoidance of destruction in pleasing God, owes much to the Gilgamesh narrative. The Epic of Gilgamest, the oldest known piece of literature (of writing) known to humanity, comes from a Sumerian story of a prince, two thirds god and one third human, who combats a beast-like man, two-thirds beast and one part human. Enkidu runs wild with the animals of the forest. When hunters complain of his freeing animals from their traps, the bored, young, celestial prince encourages a prostitute to go the pool of water where the animals nightly drink. When she appears, all animals shun her, running into the forest, except for Enkidu, who finds something in her too alluring to resist. She makes love to him; after which, in the morning, all animals of the forest shun the man-beast as somehow changed; he, having no recourse, follows her into the city from the forest, where he meets Gilgamesh, and the two wrestle for most of the day in blood combat: Gilgamesh is quicker, more skillful, but Enkidu possesses strength and tenacity. After a daylong battle, they consider their combat a draw and quickly become devoted to one another.

We can see how this compares favorably with Creation and the Garden, as well as the Fall, and later narratives. Enkidu loses his innocence in the awareness of sexuality, loses his paradise of roaming free with the animals, and becomes mature, having nowhere to turn but to the city and the future. Together, Enkidu and Gilgamesh merge to become one human being, with each possessing different aspects. Their journey together ends with Enkidu’s untimely death, which Gilgamesh refuses to accept. He journeys to find the answer to immortality from the only mortal never to have died: Utnapishtim, who received instructions on building a boat in order to escape the gods’ wrath, which determined to end the world by flood. Gilgamesh makes the arduous journey, finds Utnapishtim, learns of immortality’s secret—a plant with a berry that grows only in a deep pool of water—acquires the plant, and, upon returning to the body of Enkidu, decides to engage in a sort of ritualistic cleansing before approaching the body. Unfortunately, as he bathes a serpent slithers from the forest, devours the berry, and stops long enough to shed its skin—a sign of immortality—before returning to the primeval forest.

Jacob is the favored Gilgamesh, the son who will prevail and take unto himself all the qualities of the brother whom he supplants. His immortality, like that of Gilgamesh, is learned by danger, journey, and the gods’ providence. Gilgamesh learns that immortality lies in the remembrance we afford others during life; so too, Jacob is the father of nations, which recognize him as the father to a chosen people. Like Gilgamesh, who’s mother is mortal and helps to interpret her son’s dreams, Jacob takes instruction from his mother and becomes the first of many dreamers in the Hebrew Scriptures, those who realize their destiny from the prophetic nature of sleep.

Notice as well that Jacob becomes God’s favorite by means of an expulsion of the other: not only his brother Esau, but the Egyptian Hagar’s child, Ishmael, much like his destiny would lead to the expulsion of the Canaanites, first owners of the land promised to those fleeing Egypt. Ishmael remains at home in the wilderness, whereto he is sent, and becomes a skilled hunter and bowman. The comparisons between the two epics, that of Gilgamesh and that of Jacob, have numerous comparisons—much as we discussed with regard to the Noah narrative—so that we’re left wondering: Were these stories familiar to all the peoples of and have a common source for the peoples of Mesopotamia, or did one (or many) cultures borrow from the original?

One of the characteristic qualities of the J writer are the many puns at work in these narratives, much like the adama of Chapter 2. One play upon words here has to do with the quality of Esau, his reddish hair and reference to the “red stuff” which Jacob cooks in order to force the concession out of his beastly brother, too hungry to think about what he does. The Gilgamesh tablet informs us of Enkidu’s description: “shaggy with hair was his whole body” (Tablet 1), which compares to Genesis’ account of Esau’s birth as “a hairy mantle all over” (25:25). Speiser’s excellent commentary in the Anchor Bible edition of Genesis makes a further point: business transactions in the Near East, he notes, may have been subject to legal norms but were as well looked upon to some extent as a “game.” Here, we may think of Job and God’s court advocate Satan questioning the other legal combatant, God Himself, to enter into legal dispute; so too, though abstract legal judgments be misapplied, the game turned on the true meanings of words and sounds—what we and other generations have delighted in as puns, so that the original meaning of Jacob’s name was “may God protect” or “may God hold firmly” but became familiar, because the original verb had gone out of use: all that remained was “heel.” Numerous examples of the previous can be seen in the study of Shakespeare’s plays, wherein such words as “die” have more to do with the colloquial sense of sexual climax than the more serious sense with which we would use the word—thus the paradox and double-sense of the word that causes pause when the juvenile Juliet, having married but not yet known her wedding night, calls upon night and so casually mentions that which will occur after she “dies.”

The gamesmanship begins with the birth of the twins, but it also continues the narrative game: Isaac follows his father’s lead in another deception: he passes off Rebekah as his sister rather than wife lest the Philistines kill him for the beautiful prize. We note that in both of these instances, not only are the men schemers, but the women regarded as dangerous due to their beauty. Like their relationship to God, the men are wholly undeserving; is it for this reason that Jacob labors so for his wife? Is this the balance that tells us that such a man is worthy to be chosen by God? This incident, so believe both Speiser and Albright, give rise to the idea that a single incident was remembered and rendered by two authors, especially since both Abraham’s deception and that of Isaac encounter Ambimelech, host of the Philistines or captain for Pharaoh.

Careful readers of the narrative to this point notice an important event in the narratives involving the differences between Esau and Jacob: in the first, Esau sells his birthright due to hunger, coming across as a gross barbarian willing to do anything for a bit of food; but in the second deception, we genuinely feel his sorrow and offer pity when he cries before his father for any blessing, whether for the first-born or not. The result is that others, notably Hosea (12:4) and Jeremiah (9:3), disapprove of Jacob’s behavior. So why has the J writer recorded it as such? Probably because this narrative, like so many others, shows sympathy for victims, and here Esau is the victim.

Esau will be father to the nation of

Edom, which had a political and cultural tradition with that of Israel. Birthright in this part of the world was largely a matter of

the father’s discretion, and deathbed declarations carried great weight.

What was once an ancient tradition had, at the time of the narrative rendering,

lost much of its legal authorization; but what was not lost was the whole

picture, so to speak, the plan that Yahweh oversaw for the development of a

promise, a covenant, and a general agreement made at the expense and pain of one party in the legal

binding. What is of most relevance,

therefore, is not the propriety of the blessing directed to the younger son

while the older cries out in pain that he has been duped; nor is to be found in

our asking “why can’t Isaac undue the blessing—did he have but one?

If so, what would the younger Isaac have received—nothing? as does Esau?

Why must that be? What is so binding in a ‘blessing’ that a father cannot share

his bounty with both?” The answers

lie in the literary qualities of the narratives, an additional argument for the

reading of these stories as such: tension mounts continually as we follow the

younger Isaac, disguised and aided by his mother, awaiting a blessing while

wondering if and when his rightful brother should appear, the hunt he was on, by

the way, taking less time than mother and son how allowed, with the old,

sightless Isaac touching and smelling his way toward his rightful heir.

Thus the reader becomes completely taken in, drawn into the drama, wishing for

the “underdog,” the heel, to come out on top, since we know that this has

heavenly sanction: it cannot be undone, but will last for eternity.

general agreement made at the expense and pain of one party in the legal

binding. What is of most relevance,

therefore, is not the propriety of the blessing directed to the younger son

while the older cries out in pain that he has been duped; nor is to be found in

our asking “why can’t Isaac undue the blessing—did he have but one?

If so, what would the younger Isaac have received—nothing? as does Esau?

Why must that be? What is so binding in a ‘blessing’ that a father cannot share

his bounty with both?” The answers

lie in the literary qualities of the narratives, an additional argument for the

reading of these stories as such: tension mounts continually as we follow the

younger Isaac, disguised and aided by his mother, awaiting a blessing while

wondering if and when his rightful brother should appear, the hunt he was on, by

the way, taking less time than mother and son how allowed, with the old,

sightless Isaac touching and smelling his way toward his rightful heir.

Thus the reader becomes completely taken in, drawn into the drama, wishing for

the “underdog,” the heel, to come out on top, since we know that this has

heavenly sanction: it cannot be undone, but will last for eternity.

We should notice another attribute of the Jacob narratives, because they prepare us for what comes later: the tension filled between brothers, between families, and, finally, that of nations. Much of that tension will result in outright war and the clear indications of something new: a nation with but a single god not only clarifies its differences with other peoples of the Mesopotamian or Mediterranean areas but signifies enough differences because of their beliefs that bloodshed becomes necessary.

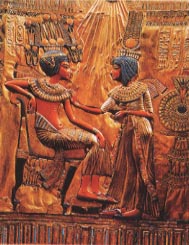

If we step back a bit, to this point we have Yahweh create a world, people it, regret the creation, and then change enough so as to acknowledge that humanity will always be wicked, despite the Creator’s best intentions; He then makes a new covenant, honors it, and eventually chooses its pater familias, the patriarch of nations, Abraham. As noted previously, this is unique for several reasons, the principal being that here a god chooses the people rather than the other way round. However, it goes deeper. What held nations together as a people in antiquity was the transference of gods; that is, the sun god may be called many things in different languages, but different peoples can offer respect to and worship of the same god. Gods are interchangeable. But when Abraham is called from Ur to go to a new place, he must have been surprised that the god he left behind went with him. All cultures share their gods, and it was common, even for the Hebrews, to worship the local gods and to therefore show their respect. If gods were to go with an individual, they were the gods of the tent (el shekinah), of the home, and worshipped as such. Suddenly Abraham learns that the god who had called him out of Ur remains with him in a new, strange land. Tension becomes the obvious result, and we see it almost immediately when Abraham travels to Egypt and has Sarai lie about their relationship.

Egypt represents a mighty culture at

the time, and, if nothing else, the earliest narratives in Genesis set us up for

the dissention and break of the allegiance of these nations and the antipathy

established and rooted far into the present.

But we also note the way that tension informs the narratives of Isaac, of Rebekah (and the same deception that his father had

used, worked as well for Isaac when he passed her off as his sister when they

traveled to the coastal land that would be known as Philistia), of Jacob and

Esau, and the parallel countries involved in their internecine struggles.

The tension is part of the family, just as the eleven sons hate the favor

bestowed upon the youngest, Joseph.

Even prior to this we note that several brothers take it upon themselves to

avenge the rape of their sister, Dinah, a massacre that Jacob fears will bring

hatred and defeat upon the tribe.

But we’re being “readied,” as it were, for the greatest break of all, that of

the exodus, the calling out of bondage of the Hebrew people and the final return

to the Promised Land, which will find national realization in the court of David

and establishment of the Temple by his son, Solomon.

narratives of Isaac, of Rebekah (and the same deception that his father had

used, worked as well for Isaac when he passed her off as his sister when they

traveled to the coastal land that would be known as Philistia), of Jacob and

Esau, and the parallel countries involved in their internecine struggles.

The tension is part of the family, just as the eleven sons hate the favor

bestowed upon the youngest, Joseph.

Even prior to this we note that several brothers take it upon themselves to

avenge the rape of their sister, Dinah, a massacre that Jacob fears will bring

hatred and defeat upon the tribe.

But we’re being “readied,” as it were, for the greatest break of all, that of

the exodus, the calling out of bondage of the Hebrew people and the final return

to the Promised Land, which will find national realization in the court of David

and establishment of the Temple by his son, Solomon.

All of these accounts speak as well to the crises at the time most scholars believe the Yawish and Elohist writers recorded their narratives, when two kingdoms emerged from the original invaders to Canaan, who defeated the people of the land with Yahweh’s help: Israel of the North and Judah of the South. Those of the South wanted a king, wanted unity; those of the North favored the rights of the individual tribes, descended from the sons of Jacob. To some degree similar to the struggles millennia later in America, some favored an united, centrally-controlled kingdom, while others opted for local, individual authority. David was that king of the South; he forged too strong a nation for others to attempt conquest, though the North failed and fell to several invaders over time. The lessons are in the past. And if we read All the literature of the Hebrews, we find connection and vitality for the present, or the time in which oral tradition gives way to written.

Israel and Edom, or the lands of Jacob and Esau, did not get along; they, much like the Israelites and Egyptians, were bitter rivals. Kind David defeated the Edomites (2 Samuel). The land of Seir was the home of the Edomites, which is a continual pun upon the latter, red, and the previous, hairy. But the numerous and memorable adventures of Jacob have many and varied interpretations, meanings, significances that readers pay attention to. With so many heroes and central characters of the Biblical narratives to choose from, we note here particular stories that seems best to inform who they are by what they’ve done, all inclusive of one person. Those of Jacob and his adventures and encounters seem too many to find a single focus. His dream of heaven, for instance, in which he sees a ladder, a stairwell to heaven, represents an excellent example. Since the loss of Paradise, humanity has been searching for a way back to God; the tower of Babel was such an attempt, if for the wrong reasons. No more does Yahweh come down; now, a particular one must go up. Jacob’s dream seems more of lost longing, realized in what Sigmund Freud will call “wish fulfillment” in having access to that which is otherwise denied. His dream employs the image of a ladder, and, as pointed out in an earlier summary, two great symbols dominate human thought: the tree and the ladder (background that branch off from a single source, or those which proceed step by orderly step). Here is the simple, if we may use that description, direct pathway to God. Thus, upon completion of the desirable dream, Jacob names the place Bethel, or, literally, El’s House, or “house of God.” Is it entirely coincidental that the names Babel and Bethel sound so familiar to us?

But the final sequence of events of

the Jacob cycle may be even more remarkable: Jacob returns to

Canaan, an event full of fear and trepidation at meeting his brother Esau after

all these years, and has a heavenly wrestling match before the break of day. When we read the narrative, we aren’t certain as to why

Jacob distances himself from his family and possessions—is it because, in

staying behind on the far side of the river, he affords himself “room to think”?

Or is he scheming once again and determining the best way to approach his

brother, who may be moved by the sight of the family preceding the brother who

wronged him so long ago?

Whatever the case, he once again has an encounter with heaven.

Here at Penuel (alternately spelled Peniel), Jacob wrestles with someone

not described more specifically; most would have it an angel, but Jacob believes

it to be Yahweh—and the narrative would seem to confirm that idea.

Here he receives a new name: no longer is he trickster or heel-grabber,

but rather Israel, or “he who wrestles with God.”

Canaan, an event full of fear and trepidation at meeting his brother Esau after

all these years, and has a heavenly wrestling match before the break of day. When we read the narrative, we aren’t certain as to why

Jacob distances himself from his family and possessions—is it because, in

staying behind on the far side of the river, he affords himself “room to think”?

Or is he scheming once again and determining the best way to approach his

brother, who may be moved by the sight of the family preceding the brother who

wronged him so long ago?

Whatever the case, he once again has an encounter with heaven.

Here at Penuel (alternately spelled Peniel), Jacob wrestles with someone

not described more specifically; most would have it an angel, but Jacob believes

it to be Yahweh—and the narrative would seem to confirm that idea.

Here he receives a new name: no longer is he trickster or heel-grabber,

but rather Israel, or “he who wrestles with God.”

Most remarkable is that it represents a turning point: this moment represents both the national and the personal. Israel is favored of God, whether nation or man. And if, as most scholars do, we ascribe this narrative to both the J and E writers (the Elohist, who probably borrowed from J and attempted to save the accounts of a people facing deportation into Babylon), we see two familiar tropes: the J writer’s head/heel trope. First, the celestial being dislocates Jacob’s leg but cannot free himself from Jacob’s grasp; for those who have experience with wrestling, as Jacob does with the stranger, they know that the necessity of any match is to control the heel of one’s opponent, wherein he can’t twist, turn, or free himself—a firm grasp upon the heel or ankle area of an opponent means a tactical edge. Second, the Eloist, as we shall see with Moses, maintains a common idea in his writing: one cannot see the face of God and live. But Jacob does, which means he’s blessed and indeed special.

I leave it to those for whom literature offers such great rewards to determine the significance of the river (a telling symbol) that Jacob does not yet cross, as well as the wrestling match, which seems to have the nation of Israel wrestling with God—afraid to let go, but suffering from the fray. Or does the story present one of personal forgiveness, reward, and a metaphoric reaching out to God in ways that may seem as dreams, but have rewards in the present reality? If nothing else, the Jacob narrative cycles reveal that the heroes of Israel, like its people, have serious flaws, but remain God’s chosen.

Moses: The Exodus and the Israelites

An Introduction Textual Analysis A Brief Synopsis of Exodus The Literary Qualities of Exodus

Moses: Who Was He? Comment on Narrative Episodes Hebrew Poetry

Knowing how to begin this summary about the most famous of all Hebrew narratives, or, more commonly referred to as the Moses of the Old Testament by Christians, poses difficult problems at best, and at worse some ideas that few would accept, most of all conservative Christians. The idea of Biblical scholarship already draws a line in the sand, so to speak. How does one convince people who believe that God’s call, which can come at any time to anyone, no matter his station, intelligence, or societal relevance, can change not only his destiny but all who will but hear and obey? Isn’t this one of the lessons of Moses’ call by Yahweh in the desert?

On the other end of the spectrum we have archaeological, linguistic, historical, literary, cultural, textual and biblical scholars (and by these adjectives we mean an enormous range of those interested in the Bible, many of whom are unknown to day-to-day believers, but do the work of the scholarship that many of the faithful take for granted), who, no matter how much they publish, are read only by the educated few because no one else has the where-with-all or the curiosity to understand their writing, much less their findings. In other words, we have people who will give more credit to that one blinded in a moment as opposed to the one educated for a lifetime.

Why would this be so? The answers are many and far too complex to discuss here, except to generalize a bit: we as Americans, especially, have always distrusted scholarship. It’s a puzzle, but while we tout the need for an education and try to grant to every one of our citizens an education as a right, we also denigrate it. No political battle is complete until one has called the other an “intellectual,” thereby putting the mark of Cain, so to speak, upon his opponent. We’re suspicious of educated people. We may demand the best of educations for our children, but, put to the test, we’ll opt for “commonsense” every time, as if commonsense came by default to all those who couldn’t or wouldn’t get an education: “all those who don’t have smarts, please raise your hands: you will now get ‘commonsense’.”

It may well be that an education is just for show: it gets us more money in the job market, but we don’t want separation from the group—we’re just “regular folks.” And so, in the risk of being different, we may find the price too high. It should go without saying, as well, that education and scholarship are not easy; learning takes time, commitment, and, perhaps most important, it also reveals to us (so long as we remain honest) what our limitations are. It’s difficult to accept that we may have deficiencies in what we can do or know; and so long as we never test it, we can always suggest that we could do something if we set our minds to it, but we choose differently. The temple at Delphi had above it’s entrance, “Know Thyself”—a difficult task for anyone, but it would seem to suggest that we accept what we can and cannot do in all honesty with ourselves.

Now, if you will, imagine how divisive education and scholarship may be when applied to the Bible. No longer a matter of commonsense, we now believe that God would not permit true believers to live in ignorance; they may be uneducated, but God has “called them.” We have ample providence: Moses, as mentioned, and Peter too, and we’re sure there must be others, even if we cannot recall their names at the moment. However, in all fairness we must observe that Moses was educated at Pharaoh’s court, and Peter apparently deferred the guidance of the early Church to Paul, an enormously educated man. These are the seeds of problems that do not yield apparent resolutions.

Having attended a fundamentalist, church-sponsored high school, I recall that we were on safe ground and always praised for our active minds whenever we could answer as taught or, more importantly, pose questions that were answerable according to our faith. But should we stray, that is, ask questions that put our mentors to the test, we were charged with an abundance of “self,” asking for knowledge that was beyond our kin. We once trapped a visiting lecturer about the necessities of apostolic example, upon which many Christians take their lead for such things as meeting on Sundays, regular communion, what transpires within the physical church, how to worship, and how to treat the misguided among us, among others. We asked a question about our worship that was neither set forth by Jesus nor found in apostolic example. After having cornered our visitor with a difficult set of questions, which we admittedly attempted, we heard the familiar “Does that bother you? You’re now reaching for things that God recognizes as hubris,” and that leads to proud, self-sufficiency, wherein you see no reason for God in your lives.

Today, when I teach Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, I understand better, I like to think, the Sixteenth-Century audience for whom the agnostic Marlowe wrote. The West’s literary and historical dividing line between what we have come to term medieval and Renaissance, for want of better terms, rests on the distinction of what we may know and what God has set out of bounds. Faustus wanted all knowledge; but the Good Angel tells him that some things should be beyond his search, even if they are within humanity’s reach (free will makes it possible but does not deem it necessary).

But how are we to square a lifetime of learning and grounding in the fundamentals that will “prove” belief, or at least give one the sufficient knowledge to pursue belief and faith, if we so easily dismiss the relevance of learning? The options for biblical scholarship are many, from the most liberal of seminaries to the most traditional of Bible colleges, and somewhere in-between we find university Theology departments that offer consensus scholarship without doctrinal influence. So the easy answer as to how we manage to juxtapose scholarship and faith is, of course, we do not; rather, for most, they continue to remain separate, or, at the best, we do as I did in High School, learning to defend that which we first believe. Let me offer an illustration, leaving it to the reader to position him or her as to the relevance of the above.

The conservative, traditional belief has it that Moses wrote the first five

books of the Bible, which we call the Torah, and which describe in detail

the first migrations to, the three different occupations of, and the final

circumstances that surround the occupation of the land that would become Israel,

formerly Canaan. God intends the

land for the habitation of the exiled people whom Moses led from bondage in

Egypt.

This god dictates a set of moral instructions that all people

follow—another bond or covenant between Yahweh and His chosen people, an example

to the known world—which grants the moral authority of a people who in time have

more specific laws that pertain to them alone, laws both justifying and explaining their avoidance of other cultures and other beliefs.

What follows becomes a history of this endeavor.

justifying and explaining their avoidance of other cultures and other beliefs.

What follows becomes a history of this endeavor.

Moses (and remember that no historical records beyond the Bible exist as to his existence) would have lived about 2000 BCE. The supposed record of his writings and facts of his life, however, are written in a style and with colloquialisms and records that cannot place him before about 800 BCE. Or, in other words, it’s as if a student of Shakespeare suddenly believed that people of the twentieth century not only thought and spoke as do characters in Hamlet and King Lear, but they also carried swords, wore doublets, swore loyalty to the king and country, and liked to speak in iambic pentameter—especially when upset.

The differences between the Moses of historical time and the writing of the Bible that records him are even more different (and Shakespeare is only four-hundred years removed, not fourteen hundred). Even if we ignore the differences between history and the text in verb tense—reading Canaan was, as oppose to Canaan is—that’s not the biggest of problems; and neither is the fact that the narrative uses different words for God (something no one would do lightly), or that it tells of the author’s death and things he could not know, because, we may believe, this is prophetic; yet, never mind that nothing else written at this time is regarded as prophecy—but this continues to the point of absurdity. If one chooses not to believe otherwise, no amount of scholarship will overcome the necessities of faith we may place upon our insistences.

The point to be made here is fairly straightforward: textual—much less anthropological, literary, historical, political, and all the other studies—takes no prisoners; it’s the hardcore of scholarship. If you want to know the real scholars, engage in textual studies, where scholars can offer percentages, based upon history and all known texts, of scribal error: in other words, how often will a text’s copier make a mistake? How often transcribe a line twice, how often change a circumlocution or colloquial phrase into something that doesn’t do it justice, how often duplicate a series of letters, how often divide words so as to confuse their meaning (just to get it to come out on the parchment or whatever so as to look nice or to get the line to end as it should?), how often remove a redundancy that bothers the scribe, how often to expand the material to include the speaker, the location or other information as to where they are, who is doing what? How often does the scribe confuse similar looking words that repeat in an extended manuscript that he has been working on for hours, how often make the mistake of transposing letters (as I have done dozens of times as I type?), how often add another text he knows about and respects, how often…. And this represents but the beginning.

To demonstrate my point, I quote here from the excellent Translation notes from the Introduction to the Anchor Bible: Exodus 1-18 by William H. C. Propp in order to render the idea of textual considerations more specifically:

Readers rarely ask how ancient (or modern) works have reached their hands, and whether they have arrived intact. For the bible, we do not possess the original manuscript of a single book. Rather, we have copies of copies of copies, to the nth degree. Some may have been dictated orally to facilitate mass production, some ay have been written from memory; most were probably reproduced by visual inspection, as required by Jewish law. Despite the safeguards of professional scribedom, the transmission process was fraught with peril at every step. We cannot simply flourish a Hebrew Bible and call it “the text.” In fact, even printed editions differ in trivial ways.

The aim of textual criticism is to restore, insofar as is possible, the original words of the first edition, the lost “parent” of all extant textual witnesses. Or so we pretend. In fact, even for modern works, defining “original” can be difficult. Do we give priority to the author’s manuscript, the author’s corrected proofs, the first printed edition or a later version revised by the author’s own hand? Comparable complications probably apply to ancient works.

Skipping over numerous problems, I will now summarize the evolution of the pentateuchal text. Sometime after the Jews’ return from Babylonian Exile in 539, the first Torah was assembled by a scribe whom we call the Redactor. Like a modern synagogue scroll, it contained no vowels or cantillation, only consonants and probably blank spaces to separate words and major sections. The letters were in the paleo-Hebrew alphabet not the “square” Aramaic script used today. Unlike a modern Torah, the original was probably written on five separate rolls. Ever after, the text was considered sacrosanct; it has undergone minimal development. The era of composition was over.

The Torah became the constitutions of the nation of Judah, and ultimately of world Jewry. It was transcribed into contemporary Aramaic letters c. 300 and copied and recopied by hundreds of scribes of varying and competence, who introduced countless changes into the text, mostly minor and inadvertent. These were in turn perpetuated in “daughter” MSS—although meticulous proofreading was later mandated to control the spread of error. Whether some copyists were known to be more careful than others, so that their work possessed greater authority; we do not know. It is reasonable assumption that prior to 70 C.E. master copies were kept in the Jerusalem Temple .

Meanwhile, in Alexandria, Egypt, Hellenized Jews had translated the Torah into Greek, producing the Septuagint (LXX) in the third century B.C.E. Again, we don not possess the original LXX, but copies of copies handed down in the Christian churches. Our oldest complete biblical MSS are Greek translations from the fourth century C.E., although LXX fragments from the second and first centuries B.CE. have been recovered. The various witnesses to LXX may be compared to reconstruct, more or less, the original Greek. If we then retranslate this work into Hebrew, we obtain a text often different from that preserved among the Jews. Some differences are the result of translators’ license, others of translators’ error, but many are faithful renditions of a lost Hebrew text, the LXX volarge (German: “what lay before”).

Though their numbers have considerably dwindled, in Roman days, the Samaritans were an important and populous subgroup of Jews. The Samaritan Pentateuch (Sam) differs from LXX and the standard Jewish Torah (MT), frequently agreeing with one against the other—unless the question is one of specifically Samaritan doctrine. Scholars date the prototype of Sam to c. 100 B.C.E., based primarily on its paleo-Hebrew script and affinities with some Dead Sea Scrolls. Like LXX, Sam is not one MS, but a family of closely affiliated MSS.

During the past fifty years, the Qumran caves near the Dead Sea have yielded hundreds of scrolls and scroll fragments dating from the mid-third century B.C.E. to 68 E.E. Among these are over a dozen MSS of Exodus, all fragmentary, all different from one another and all in partial agreement and disagreement with LXX, Sam, and MT. Phylacteries and mezuzoth from Qumran and Masada also contain portions of Exodus 12-13 and 20.

LXX, the Dead Sea Scrolls, Sam and MT jointly attest to a spectrum of readings in Greco-Roman times. These textual witnesses cannot be derived one from another. They rather share a common source, the object of our text-critical task. It may not be the pentateuchal autograph, only an intermediate exemplar, but textual criticism can take us no further.

To this point, the picture is much as we would expect. MSS increasingly diverge the more they are removed from their ancient prototype. But the picture appears to change abruptly in the early second century C.E. Scrolls from Wadi Murabba’at and Nahal Hever are almost identical to the later MT, and all subsequent evidence attests to the relative homogeneity of the biblical text throughout the (non-Samaritan) Jewish world. Can it be that all variant MSS were suppressed in a coup, from one end of the Diaspora to the other? If not, what really happened?

Rabbinic Judaism arose after the Second Temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 C.E. This crisis unleashed certain tendencies, stifling others. A group of sages known to posterity as the Tanna’im became, in the late first and early second Christian centuries, the arbiters for succeeding generations of what was Jewish and what was not. Dissident groups such as the Samaritans and later the Qara’ites were excluded from the fold. I suggest, then, that we imagine a wave phenomenon, coincident with the rise of Tanna’itic hegemony, resulting in the near-total standardization of all Hebrew MSS. This version naturally required a few centuries to expel its rival from the far-flung reaches of the Diaspora. But it so far outstripped its competitors in prestige, the Tanna’itic Bible became the natural basis for all scholarly work on the Hebrew text, whether by the Rabbis, the Qara’ites or the Church Fathers. Deviant MSS were no doubt preserved by some communities until they wore out. But they were not copied or cited by the experts of the day; hence, their readings have not been passed down. The appearance, from our perspective, of the Jews instantaneously adopting a uniform biblical text is probably the combined result of natural selection and the incompleteness of the record.

After the Dead Sea Scrolls, we possess no Hebrew biblical MSS until the early Middle Ages. For the interim, we have only the indirect testimony of ancient translations and citations. A Targum (Tg.) is a Jewish translation of the Bible into Aramaic, the vernacular of the pre-Islamic Near East. Dating Targumic literature is extremely difficult. Our three complete Targumim of the Torah are the fairly literal Tg. Onqelos (c. 100 C.E.?), the far freer Tg. Neofiti (c. 300 C.E.?) and the much-embellished Tg. Pseudo-Jonathan (completed c. 700 C.E. but with older antecedents). There are also Targumic fragments from the Cairo Genizah and the so-called Fragmentary Targum, akin to Neofiti I and Pseudo-Jonathan. These translations vary from MT in minor but interesting ways, confirming that the standardization of the Bible was an uneven process, and less thorough than surviving Hebrew MSS might suggest. The same is evident from deviant scriptural citations in the Talmuds.

Throughout Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages, the Hebrew biblical text was undergoing near-total standardization, down to the merest details. Perhaps as early as c. 700 C.E., groups of Rabbinic and Qara’ite Jews confirmed the basic consonantal text, refined safeguards for accurate copying and developed symbols enshrining received pronunciation, cantillation, syntactical analysis, even scribal quirks. The era of the Massoretes (“tradition experts”) reached its peak c. 900 C.E. Massoretic texts became standard for all Jewish communities retaining knowledge of Hebrew, except for the Samaritans. One should remember, however, that, despite its standardization, MT is an abstraction, a type of text attested in about six thousand medieval exemplars that disagree in numerous but relatively minor ways. Properly speaking, a Massoretic text is any biblical text accompanied by vocalization, trope and marginal annotation in the style of the Massoretes.

Few ancient variant readings survive in MT tradition; most differences among MSS are new mistakes or developments, and in any case are rarely more serious than “Egypt” vs. “land of Egypt.” But we should remain open-minded and alert. Individual readings, though generally transmitted “genetically” from parent to daughter MS, may also leap “infectiously” from MS to MS, as when a scribe compare existing texts or consults his memory. Thus, even if Rabbinic authority prevented deviant MSS from being reproduced in toto, individual variants apparently found shelter here and there in otherwise Massoretic texts. We in fact find sporadic agreement between MT MSS and LXX, Sam, the Dead Sea Scrolls, etc. In any case, since there is no such thing as the MT, it is arbitrary to select on prestigious text—the Aleppo Codex, the Leningrad Codex, the Second Rabbinic Bible, etc.—as sole witness. (Propp 42-45)

As for the difficulties of translation and the possibilities of error, if one should respond that God would not allow such a thing, I can offer no rebuttal. If I did, I would hold up as evidence the fact that we have NO original text: we have the LXX (Septuagint) from the tradition of the seventy Alexandrian scholars who translated the Hebrew into Greek (the world language after Alexander), the Targums, the supposedly translated texts into Aramaic, the Samarian text, supposedly also based on earlier manuscripts, the Massoretic text, based on medieval Hebrew translation, and on it goes, again and again—in other words, we have translations, based on translations, based on translations, based on more translations.

To repeat, no UR text (German for “First”) exists; so what do we follow? You’ll notice that we haven’t even begun to discuss the Geneva, Bishop’s, King James, Revised Standard, New Jerusalem, International, Phillips, and other translations familiar to readers of the Bible today. And each follows a discipline of scholarship and practices with regard to how to translate words, what notes to add (if they do), what scholarly position to take with regard to difficult or unfinished bits of text (here we get that terrible distinction between “liberal” and “conservative”—more often referred to as “traditional”), or what our “overview” may be. Most of these decisions never appear to readers, unless they read the translator’s introduction, which most often has brevity in order to diminish and yield the scholastic to the divine, which, paradoxically, is suffused unobtrusively throughout the text. This is much like the old joke, though I have indeed heard it in earnest, that “whatever the Apostle Paul spoke in the King James Version is good enough for me.”

In sum, Biblical scholarship renders a more complicated picture of a text in more need of study than most of us wants to admit, much less pursue. Having had a course limited to textual scholarship when studying for a degree in Shakespeare, I became so overwhelmed with the responsibilities and justifications of standing behind a famous bit of text that was but an exercise, I froze like the proverbial animal before headlights. But I understand somewhat better the severe punishments that awaited the Reform editors of the Bible should they make errors—not forgetting the death sentences for those who had no church or state sanctioned authority to translate. In lieu of understanding textual studies in general, and how they apply to biblical scholarship in particular, we assure ourselves that God would not permit us to live in error or to read a poorly rendered translation, and so we “choose” not to engage its scholarship.

But the counter to this is that we have minds, and good ones: why is it that

other generations have spoken several languages (Queen Elizabeth I was

conversant in seven, including Hebrew and Greek, and she never claimed to be a

Biblical scholar), have studied all past scholarship, have learned the  cultural

differences (and here, if one claims it doesn’t matter, I’ll simply ask why most

all of us no longer tolerate multiple wives, slavery, and mass extinction in the

name of God), and have engaged the textual studies necessary to know the basics

of translation and when to trust a source?

Why? The answer is probably because it’s too much trouble; but

equally true is that many of us have not the education or the necessary

facilities of intellect to do so.

cultural

differences (and here, if one claims it doesn’t matter, I’ll simply ask why most

all of us no longer tolerate multiple wives, slavery, and mass extinction in the

name of God), and have engaged the textual studies necessary to know the basics

of translation and when to trust a source?

Why? The answer is probably because it’s too much trouble; but

equally true is that many of us have not the education or the necessary

facilities of intellect to do so.

However, such answers may be equated to one believing that, because everything works out for the best, if he’s laid off, has no money, and can’t support your family, he should sit by the phone in the assurance it will ring. In fact, if the parallel illustration holds true with what precedes it, it would be unchristian for him to make an effort or to try to support his family, because it places more responsibility on us than it permits for faith in God. Why is study so different?

The Moses narratives are not so easy to understand as we may think. The following information tries to balance scholarship, tradition, and biblical importance into one. But should it fail for the reader, he or she must determine why, based on what one can learn and determine individually, as opposed to what the reader has been told, read, or memorized from the past. If the above propositions, or the statements and questions to follow, make one uneasy, settle it now, for reasons of scholarship, faith, or curiosity—but do it and learn.

Libraries remain repositories of learning, with texts full of information. Especially now, within an era hallmarked by the instant gratification of suspect knowledge available through the Internet, one’s abilities and desire to learn will always be challenged. In failing either to accept or to attempt an effort that meets those challenges, we surrender the enormity of human potential, whether one attributes the repository as that granted by God or by humanistic curiosity: blasphemy exists in a multitude of forms.

So, where does that leave us with regard to the writing of the Torah in general, but the book of Exodus in particular? Tradition lightly dispels the the difficulties of much of the above, invoking Moses' prophetic powers. The logic is unassailable, if only we allow for the supernatural. In theory, a true prophet could have predicted the Canaanites' demise, the coronation of Saul, his won death and Persian-period spelling. But the critical historian is rather drawn to conclude that the Mosaic authorship of the Torah is just another legend, or at best an exaggeration. In fact, the Pentateuch never explains how it cam to be written. The earliest allusion to a Mosaic Pentateuch come from the postexilic period, when most scholars date the Torah's editing and promulgation (Ezra 3:2; 6:18; 7:6; Nehemiah 1:7, 8; 8:1, 14; 9:14; 10:30; 13:1, etc.).

If Moses did not write the Torah, who did? Most likely several people, for, as is well known, the Pentateuch is rife with internal contradictions and duplications (doublets). Each, taken alone, proves nothing; traditional Jewish and Christian scholars have effectively dealt with most of them piecemeal. Cumulatively, they constitute a major challenge to the tradition of a single author. It rather appears that an editor (or multiple editors) produced the Torah by combining several written sources of diverse origin, relatively un-retouched, into a composite whole. This is the Documentary Hypothesis [and here, let me remind American readers of the unfortunate definitions we have ascribed to words such as "hypothesis," "theory," and "myth"].

The number of sources appears to have been small. First, no story is told more than three times. Second, it is hard to imagine an either countenancing so many duplications and inconsistencies were he at liberty to weave together isolated fragments from dozens of documents. Third and most important, if we arrange the doublets in four columns and then read across, continuity and consistency replace contradiction and redundancy. These columns approximate the original sources.

While the exact process by which the Torah coalesced is impossible to reconstruct, here is a commonly accepted model, which may be pretty close to the truth. After the demise of the Northern Kingdom of Israel, refugees brought south to Judah a document telling the national history from a Northern perspective. We call this text "E" and its author the "Elohist," because God is called (hā) 'ělōhîm' (the) Deity prior to Moses' day and sporadically thereafter. In Judah, a scribe we call "Redactor" combined E with a parallel, southern version, "J," which calls God "Yahweh" throughout (except in some dialogue). We call J's author the "Yahwist." The composite of J and E is known as "JE."

Precisely a century later (621 BCE), a work called "D," essentially the Book of Deuteronomy, was promulgated to supplement JE. It purports to be Moses' final testament deposited in the Tabernacle (Deut 31: 24-26) and rediscovered after centuries of neglect (2 Kings 22). In fact, D appears to be a rewritten law code of Northern origin, with stylistic and ideological affinities to E. The author/editor of D. the Deuteronomistic Historian, also continued Israel's history down to his own era, producing the first edition of Deuteronomy through 2 Kings (a second edition was made in the Exile). Some think JE was also reworked so that the Deuteronomistic work properly began with Creation. If so, however, the editor added relatively little in Genesis-Numbers.

If D was intended to complement and complete JE, another work, the Priestly source (P), attempted to supplant JE with its own partisan account of cosmic and national origins. The date of P is disputed, with most scholars favoring a late pre-exilic, exilic or early postexilic date (i.e., c. 700-400). Subsequently, a second priestly writer, the final Redactor (R), thwarted P's purpose by combing it with JE, inserting additional genealogical and geographical material. The Redactor also detached D from Joshua-2 Kings, producing the Pentateuch.

For Exodus, our main concern is with P, E, and J, although there is some D-like language, too. It is likely, moreover, that the Song of the Sea originally circulated independently and should thus be considered another source. P is the document most easily recognized, thanks to its characteristic vocabulary, style and agenda. P's main concern is mediating the gulf between God's holiness and the profane world through priestly sacrifice. P stresses distinctions of clean and unclean, the centrality of Tabernacle service and the exclusive right of the house of Aaron to officiate. Its rather austere Deity sends no angelic messengers. P also evinces a scholarly interest in chronology and genealogy. In JE, in contrast, sacrifice is offered by a variety of men in a variety of places. Thee is more interest in narrative and character portrayal, less in ritual, chronology and genealogy. god communicates through angels, dreams or direct revelation.

The most striking difference among J, E and P involves the divine name. E and P hold that the name "Yahweh" was first revealed to Moses (3:14-15 [E]); 6:2-3[P]). Previously, God was called "God" (el)," God Shadday ('ēl šadday)" or "(the) Deity ([hā]) 'ělōhîm')." In J, however, the earliest generations of humanity already use the name "Yahweh" (Gen. 4:26, etc.); Moses is merely granted a more detailed revelation of God's attributes (Exodus 34:6-7). Consequently, virtually any text prior to the Burning Bush containing the name "Yahweh" is from J. When it comes to the Mountain of Lawgiving, however, J and P line up against E and D: J and P call it "Sinai," while in E and D it is "Horeb." A final difference between J and E is that the former calls Moses' father -in-law "Reuel," while the latter uses "Jethro" (Jethro/Reuel does not appear in P or D).

Because separating J from E is difficult outside of Genesis, prudence would dictate partitioning Exodus simply between P and JE. However Propp undertakes the dubious task of disentangling J from E, because the results are surprising. If J is the dominant voice in Genesis, in Exodus we probably have more E than J. This flies in the face of all previous scholarship, which unanimously ascribes the bulk of non-Priestly Exodus to J. This is simply an unexamined dogma, however, put baldly in D. N. Freedman's methodological postulate that, "in dubious cases, one must opt for J rather than for E." In fact, we find far more E than J in Exodus. Recurring idioms, characters and themes all point to the Elohist.

[Propp offers an extensive argument, verse by verse, chapter by chapter : I advise the textual scholar or interested party in textual studies to pick up at this point, p. 51 ff. in the excellent Anchor Bible: Exodus 1-18.]

Outline of Exodus

I.

Exodus: The Deliverance Traditions (1-18)

A.

Israel in Egypt (1)

B.

The Early Moses (2-4)

C.

Plagues (5-11)

D.

Passover (12:1-13:16)

E.

Exodus from Egypt (13:17-15:21)

F.

Wilderness Journey (15:22-18:27)

II.

Sinai: The Covenant Traditions (19-40)

A.

Theophany on the Mountain (19)

B.

Law and Covenant (20-23)

1.

Ten Commandments (20:1-17)

2.

Book of the Covenant (20:18-23:33)

C.

Covenant Confirmation Ceremony (24)

D.

Tabernacle Design (25-31)

E.

Covenant Breaking and Remaking (32-34)

1.

Golden Calf (32)

2.

Covenant Renewal (33-34)

F.

Tabernacle Construction (35-40)

Hebrew Scriptures identify their books of scripture by how they begin the narrative; thus, Exodus is called ’ēlle[h] š∂môt (“These are the names of…”), rendered in the Greek as Exodos (“road out, exit”), and Latinized as Exodus for the second book of the Torah. After what may be approximately three centuries, the Egyptians fear the numbers of the Hebrew people; so Pharaoh first enslaves them and then determines that he must kill the male newborn children. The king’s daughter, spares a child she finds in the water, and raises him in the palace as her own.

We are as well, that Pharaoh will not listen to Moses and his brother Aaron, who

accompanies him, because Yahweh has hardened the heart of the king so as to not

listen to pleas. The resulting miracles

worked by God become ten plagues against Egypt, concluding with all Egyptian

firstborn dying on a night that sees the Hebrews spared, since they have been

instructed to anoint their door frames with lambs’ blood.

worked by God become ten plagues against Egypt, concluding with all Egyptian

firstborn dying on a night that sees the Hebrews spared, since they have been

instructed to anoint their door frames with lambs’ blood.

Pharaoh releases the Hebrews but almost immediately changes his mind, seeking to attack them with their backs to the sea; Yahweh intervenes again, and the sea parts, permitting the Hebrews, lead by

The jubilant Israelites, descendants of the twelve sons of Jacob, whose named was changed to Israel, wander into the wilderness on their way back to God’s mountain, Mount Horeb, also called Sinai. Many scenes of discontent and miracles take place, as the Israelites grow discontented and scared but are saved by miracles of food from heaven and protection against tribal attacks. At the foot of the mountain, Moses, with the aid of his father-in-law, Jethro, establish what is called the Israelite judiciary, and Moses reveals the Covenant Tablets he received of God, as well as instructions for building the earthly habitation of God, the Tabernacle.

However, in Moses’ absence, the weak Israelites again backslide, making and worshipping a golden calf. In anger, Moses smashes the tablets received from God, but manages to intercede with God on behalf of the Israelites, renews the Covenant, and receives additional laws from God. The craftsman Bezalel directs the construction of the Meeting Tent, which is consecrated shortly before the anniversary of their departure from Egypt.

The Literary Qualities of the Narratives

The ironies of the early Moses narrative are great, indeed; for, even as Moses is saved by water, so too Pharaoh’s army will be destroyed. And it becomes clear to readers that water figures into the narrative in many ways: the manner in which the child Moses is saved and the command of Pharaoh for destruction of the children share similarities in verb form, so that an irony between “throw” and “place” becomes apparent in the Hebrew, as if the mother of Moses obeys the order of Pharaoh but is saved by his daughter by means of the death sentence. Others have noted the importance of the fact that the princess then hires the mother of Moses to act as wet nurse for the child and so not only raises her own son but also is now paid to do so.

But water once again becomes an irony in that the Nile fills with blood by one of the miracles wrought through Moses, paralleling the bloody business of killing children through the orders of Pharaoh to fill up the Nile with the bodies of children. Moses’ young body was one that was saved by the method of the reed basket, fashioned by his mother, who in turn saves his people in the same manner—especially relevant for the irony of the tale is that many scholar believe, and some translate, “Red Sea” as “Reed Sea” (called as well the Suph Sea, which translates as “reed”) for the accidental corruption by scribal error that mistook one body of water for another. Or, do we also see salvation for the future in the small ark that saves the Moses child, which equates to the flood that destroys all but those found righteous in God’s eyes?

If nothing else, we’re reminded of the many thematic qualities that water, especially, has in fairy tales and other various forms of literature. This more properly would take us into the arena of Carl Jung, who postulated the idea of all humanity being born with a genetic set of imprinted archetypes which humanity then uses to make associations, for expressions, and as means for understanding ourselves and relation to others. Jung called such archetypes “universal,” differentiating them from “particular” archetypes, those that a society imprints upon its children through its stories and literature (thus, some refer to these as “literary” archetypes as opposed to “particular”). Jung has much to say about the use of archetypes as they relate more specifically to faith, especially in his lectures on Christianity (see Jung and Christianity in Suggested Reading)

Other actions become too apparent to dismiss: most importantly, Christians will use the anagogic mode of allegory (also referred to as typological) to interpret the “Passover” in Exodus to the Last Supper and subsequent death of Jesus. Jesus becomes the paschal lamb, offering up his blood so that the believers within may find salvation—so Easter supplants Passover, reminding us of God’s saving grace, which, more specifically through the Apostles example and directives of Jesus will entail a specific physical action associated with water, baptism, which then links one to the death of Jesus and birth into a new life, an adopted child of God (which for Gentiles, becomes even more significant, since the adoption becomes available only after Jesus’ death, resurrection, and transfiguration).

Consider too, as Propp does, the role that women play in the narrative, and how evenly balanced they are: the Hebrew women are distinguished for the ability to bear and their fast, easy labor, an excuse used at the first of the narrative to explain why some have not died as Pharaoh so ordered. Moses’ own mother and sister see to his survival, which becomes assured by the princess and her maidservant; later, Zipporah, will again save Moses from Yahweh’s attack in the desert. Thus, even as Yahweh pronounces that He is the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob several times in the narrative as more general background, so too we are reminded several times of the women involved in Moses’ past who have delivered him more specifically for his role as God’s servant.

We need as well to note two other vital details about the narrative quality of how Exodus begins and why it becomes such a memorable and successful story. The first of these is the familiarity of a tale where the child is saved despite his abandonment, so that we are accustomed to adoptive parents, the illustrious and exceptional nature of the child becoming known as he grows, and finally his coming into his own, either by reuniting with his original parents or by fulfilling his exceptional destiny. Folklorists recognize the repeated use of the design in various disguises, such as Romulus, Oedipus, King Arthur, Snow White, and on it goes. Propp mentions a nearly identical tale from the Assyrian narrative of Sargon of Akkad (c. 2300 BCE), wherein the noble hero is saved by being placed into a reed basket before being cast into the water, drawn out by Aqqi, the water drawer, is loved by Ishtar, goddess of Love, and reigns as king. Other such stories include the Egyptian, involving Seth and Horus, and the Hittite tale that also involves a princess, a child set adrift in the river, its discovery by gods, and its maturation into greatness. Similar stories to that of Exodus are found in Egyptian, Assyrian, and Hittite societies, but the Sargon story is closest in time to the one we have in Exodus, and scholars know as well that the Sargon narrative spread not only eastward, but westward throughout the lands south of the Mediterranean and Mesopotamian regions, but northward as well, and probably into Canaan.

Virtually all peoples have tales that could be referred to as “adoption” narratives: for instance, Abram takes a servant as wife and has an adopted heir, King David is called Yahweh’s adopted son (Psalms 2), and Yahweh adopts the nation of Israel, which various books describe as Israel being the foster child, or the wayward child found by God, and the like (Deuteronomy 32; Ezekiel 16; Jeremiah 31; Hosea 11, and others).