What

Is

The

Bible?

The

question posited by the title of this introductory essay may not be as simple as

many would make it. The Bible

represents many things to many people. For

some, it proves the inspired word of God, while for others it remains a fine

moral code, contains interesting historical accounts of a people, a culture,

providing all that literature allows, most especially the epic—a literary

genre that tells the history of a people, focusing on a specific hero, with

action-filled travels, containing experiential deeds that affect the people who

witness them, involving violence, and the often larger-than-life exaggerations

of the one who stands for the many. What

we term the “New Testament” more than qualifies.

But the Bible has also been termed the most important

work to influence Western Civilization, which undoubtedly remains true.

It has also been termed the most influential work that has NOT

been read by most people,

which undoubtedly proves equally true.

The literary critic Harold Bloom has a term for those works, events, or

passages in literature which we believe we know, but when read closely (often

for the first time) turn out to be different than what we’ve been led to

believe: he calls such things a “facticity.”

This cumbersome word manifests what most people, who would swear

otherwise (ironically on a stack of unread Bibles), deny.

But how well do we know what the Bible says, whether we believe it to be

the word of God or not?

which undoubtedly proves equally true.

The literary critic Harold Bloom has a term for those works, events, or

passages in literature which we believe we know, but when read closely (often

for the first time) turn out to be different than what we’ve been led to

believe: he calls such things a “facticity.”

This cumbersome word manifests what most people, who would swear

otherwise (ironically on a stack of unread Bibles), deny.

But how well do we know what the Bible says, whether we believe it to be

the word of God or not?

Let’s begin with a test, easily self-graded by the

taker: if we accept the Bible as the word of God, a work that has come down to

us today from the Koiné Greek, some Aramaic, and Hebrew—which was lost but

duplicated from Greek copies—how much Hebrew, Aramaic, and especially Greek do

you know? How well?

Forget the subtleties—how well do you write and speak any of these

languages? If you answer “not

well enough” (a generous if too-trusting response), then why don’t you?

If the Bible represents the accepted word of God, and God’s word

determines your eternal destination, why would you trust others to interpret

that for you? Are you willing to

accept without question someone else, one who often does not know the languages

either, as your guide to eternal salvation?

What will you say at Judgment? “Gee,

I believed this other person because he or she said he spoke for You, and he

said….” Will that work for you?

Really? What about God?

Now you’re getting, I trust, the problem with

Biblical study. It isn’t enough

that America has dozens upon dozens of Christian sects, or more than a few

different Jewish ones, but consider the world: only Mormons believe that God did

something special in America, although one would think that all Christian

denominations believe so to hear the televangelists tell it.

Yet, who among us, when honest enough, does not entertain the question of

“what if?”—as in, “what if I had been born in the Northeast as opposed

to the South and the so-called ‘Bible Belt’”?

“What if I had been born to parents who were atheists?”

“What if I had been born in a country of predominantly Moslem

belief?” Many will answer that

“God has designed some plan so that I would inherently receive the truth”;

this answer always uncomfortably strikes me as what we hear when one survives a

disaster when the majority of people die, and then tells the listeners: “All I

can say is that God was with me.” So, He wasn’t with the others?

What special relationship or plan does God have with you other than those

who died? Does this person continue

to live his life as before, or does he sell all that all he possesses…?

The Greeks who composed, directed, and played the tragedies

of the fourth century B.C.E. (get comfortable with the initials that stand for

“Before the Common Era” and “Common Era”—they’re

much more neutral in historical terms, and, as we shall see later, more definite

in their suggestion) had an answer to some of what has been proposed above: no answer

to life exists, no reason why some die and some live, why the good suffer

and the evil often succeed, and therefore, if we acknowledge that life doesn’t

make sense, we create: art provides answers to the unanswerable, since we

can formulate events and outcomes as we will.

In other words, art steps in and gives momentary explanation to the

inexplicable. Essentially, this is what the Bible does for many: it

provides answers to the unanswerable by attributing the mysteries of life to

God’s plan. We don’t

know, but God does.

For

some, that comfort suffices; for others, it does not.

For those who seek comfort in a mysterious attribution to God, the belief

that God speaks through our pastors, preachers, priests, clerics, or those who

has received “the call” always replaces the need for or the guilt from not

knowing what the Scriptures really say. But

this is merely another point of contention, because many are not or ever will be

willing to fawn off such responsibility for an eternity. And what is our defense for such skepticism, for study, for

questions, for self-knowledge? Intellectualism

or some reference to elitism: God must love the ignorant, common folk because He

made so many of them; or, some people just try to get too smart.

Ask yourself, honestly: if you believe that the Bible

represents the word of God, would you trust eternity to a man who got the call

after being struck by lighting atop a tractor, or would you rather that your

spiritual guide, one whom you trusted, one who knew the original tongues,

studied the biblical texts most of his or her life, and had a mind that used most

of its vast capabilities? And if

you entertained the former, would you find yourself in league with the ancient

Greeks who found suitable substitutes for what we don’t know—their only

means of comfort?  If so, you’re

in the arena of art. Or if

you answered the second, wouldn’t you wish that this person represented you or

came to your defense when asked the difficult questions of faith and what you

believe?

If so, you’re

in the arena of art. Or if

you answered the second, wouldn’t you wish that this person represented you or

came to your defense when asked the difficult questions of faith and what you

believe?

So what are we getting at here? First, that even the majority of those who regard the Bible

as an eternal guide to salvation know precious little of what it really says and

trust to translation and trusted guides to tell them what it means, how it

impacts upon their lives, and whether they are adhering to its precepts.

Second, that the Bible is, to understate, a vastly important influence

upon Western thought and belief. For

even should one not believe in its inspirational tenets, it cannot be denied

that it influences for good or ill everything we say, do, or think.

Even atheists will tell you that the Bible, most especially the King

James translation, remains the most beautiful and powerful of Western works.

This, then, brings us to our next important idea: the

Bible does not reflect a tightly constructed arrangement of practices, promises,

or purpose. The word comes down to

us from the Greek, translated into Latin, and now English, meaning “Books.”

Within its covers, we find laws, history, poetry, biography, narratives,

letters, and revelations. And we

also must acknowledge that much of what we have in our hands didn’t occur to

the people for whom it happened as essential enough to demand recording—that

awaited later generations. The

Sumerian epic Gilgamesh, for example, remains far older than Genesis, and

the epic has within it a god-fashioned man, a type of fall, movement from

paradise into a degraded state, a snake who figures prominently in loss,

disappointment, and despair, a flood, and one among all of mankind deemed worthy

of saving—so he builds a boat. Does

this prove that these “Biblical” events really took place?

Or does it mean that neighboring cultures freely borrowed from one

another in their myth-making?

Let’s not forget, as well, that all oral stories

change over time until finally a society has enough vested in its past (it is our

epic, after all) to “authorize” its history; that is, a society comes to a

point at which it says, “no more fooling with these stories, adding something

here, forgetting something there; this is it; from now on we’ll all

agree that this is what occurred.”

That’s what we term “authorization.”

Gilgamesh became authorized, and so did the many Hebrew accounts

of their past. It was not, in fact,

until the early fifth century C.E. that Christian leaders decided which books

were spiritually guided and which were not, even as it comes as a surprise to

many that the Gospels, the history of the life, events, and death of one who

claimed to be a prophet of God, Joshua (Jesus, in the Greek), were not recorded

until many years after his death, at least thirty, some as many as seventy.

And why would that be? Because,

you may answer, there was a need to “authorize” those events and that life?

The same books that were accepted in this authorization

served until the Sixteenth Century, when the “Protestors” of the Church (the

Reformation—ever after to be named “Protestants”) demanded that a few of

the accepted texts be left out. And

so for Catholics today seven accepted works exists that one won’t find in a

Protestant Bible. We’ve come to

term those we do accept as the “canon.”

But different faiths have different canons.

In what Christians presumptuously term the “Old Testament,” we find

fourteen disputed books, which we now name the “Apochrypha.”

Jews count their recordings of ancient events and God-inspired writings

as twenty-four; but remember: this is, in many instances for Christians,

dividing works into two parts; in other instances, it depends on accepted or

rejected writings as being divinely inspired.

For most Protestants today, the Bible consists of sixty-six books

(thirty-nine of which are “Old”), while the Catholic Bible has seventy-three

(and we haven’t even considered the Mormon faith’s Book of Mormon, which

serves as another testament to the history prior to and the divinity of Jesus

Christ (“Joshua, the Messiah” or “Anointed One”).

So, due to space and time, let’s divide the books

according to what most Christians denote as the “Bible,” taking for our

guide the King James Authorized Version:

The so-called “Old Testament” (testamentum,

a Latin word meaning “covenant”) has

|

The Law (five books): Genesis, Exodus,

Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy (which Jews refer to as The Torah). |

|

Historical Records (twelve): Joshua, Judges,

Ruth, Samuel (I and II), Kings (I and II), Chronicles (I and II), Ezra,

Nehemiah, and Esther.

|

|

Poetical works (five): Job, Psalms, Proverbs,

Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon.

|

|

Prophecy (seventeen books, five of which are

called “major,” merely because they’re longer than the others):

Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Ezekiel, and Daniel (the “minor”

prophets are shorter works): Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah,

Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi. |

Another way of stating the above, is to see the works as Law; Prophets; Writings, as follows:

Canons of the Old Testament:

|

Hebrew

Bible: TANAK

I. Law (Torah)

Genesis

Exodus

Leviticus

Numbers

Deuteronomy

II. Prophets (Nevi'im)

A. Former Prophets

Joshua

Judges

1 Samuel

2 Samuel

1 Kings

2 Kings

B. Latter Prophets

Isaiah

Jeremiah

Ezekiel

Book of the Twelve:

Hosea

Joel

Amos

Obadiah

Jonah

Micah

Nahum

Habakkuk

Zephaniah

Haggai

Zechariah

Malachi

III. Writings (Ketuvim)

Psalms

Proverbs

Job

The Song of Songs

Ruth

Lamentations

Ecclesiastes

Esther

Daniel

Ezra

Nehemiah

1 Chronicles

2 Chronicles

|

OLD

TESTAMENT

Genesis

Exodus

Leviticus

Numbers

Deuteronomy

Joshua

Judges

Ruth

1 Samuel

2 Samuel

1 Kings

2 Kings

1 Chronicles

2 Chronicles

Ezra

Nehemiah

Esther

Job

Psalms

Proverbs

Ecclesiastes

Song of Solomon

Isaiah

Jeremiah

Lamentations

Ezekiel

Daniel

Hosea

Joel

Amos

Obadiah

Jonah

Micah

Nahum

Habakkuk

Zephaniah

Haggai

Zechariah

Malachi

|

OLD TESTAMENT

(Roman, Greek, Slavonic)

Genesis

Exodus

Leviticus

Numbers

Deuteronomy

Joshua

Judges

Ruth

1 Samuel

2 Samuel

1 Kings

2 Kings

1Chronicles

2 Chronicles

Ezra

Nehemiah

Tobit

Judith

Esther and Additions

Job

Psalms

Proverbs

Ecclesiastes

Song of Solomon

Wisdom of Solomon

Ecclesiasticus (Sirach)

Isaiah

Jeremiah

Lamentations

Baruch and Letter of Jeremiah

Ezekiel

Daniel and Additions:

Susanna

Song of the Young Men

Bel and the Dragon

Hosea

Joel

Amos

Obadiah

Jonah

Micah

Nahum

Habakkuk

Zephaniah

Haggai

Zechariah

Malachi

1 Maccabees

2 Maccabees

|

*

Book

names in italics are the apocryphal books of the Roman Catholic canon, sometimes called the deuterocanonical books.

Because the origin of the Hebrew Bible is far

distant from us, we will need to recover the original historical and geographical setting of the Hebrew Bible in order to understand and appreciate

it. In so far as we are able, we must to try to see the world as David, Isaiah, and Ezra saw it. As mentioned above, it seems strange to us that these

people never knew the "Scriptures." To understand the Hebrew Scriptures today, we need to draw upon the discoveries of generations of

historians, archaeologists, and biblical scholars, those who have pioneered scholarship largely through archaeology and the interpretation of what has

been discovered, much as scholars were shocked and delighted to find the tablets of the Epic of Gilgamesh in the Nineteenth Century, which told

of Sumerian history and gave evidence of such things as "biblical" events: the flood, a paradisial story, and the story of a god with traits

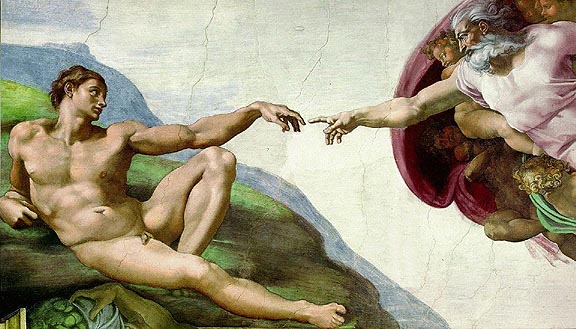

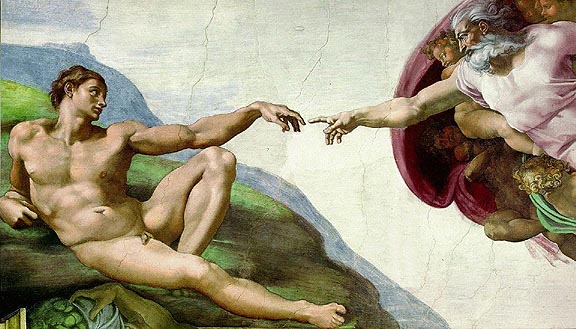

of humanity, and a man with traits of a god. In other words, we have the idea of a creature created in God's image.

One can easily see

other parallels in the Gilgamesh epic. But most exciting for archaeologists and theological scholars was that the tablets pre-dated the

biblical accounts by at least a thousand years. It's hard to say which historical find has more significance--the tablets of Gilgamesh or

the Dead Sea Scrolls discovered in Palestine caves in the 1940s. Scholars still pour over these latter findings, but because of secrecy, and

international diplomacy/jealousy/paranoia/and a host of other reasons, scholars still do not know all that may be contained in those records. If

nothing else, we know more about the many Hebrew sects that co-existed about the time that the historical figure of Joshua ("Jesus" in the

Greek) may have lived.

What is certain, however, is that the history of Israel is intertwined with the

histories of many ancient nations. In Mesopotamia, the Sumerians pioneered civilization and were followed by Babylonians, Assyrians, Hurrians,

Amorites, and Arameans. In addition, the Egyptians, Hittites, Phoenicians, and Philistines interacted with Israel and were significant factors in

determining the directions Israel's history was to take. Historians, on the basis of ancient documents and archaeological discoveries, have been able

to reconstruct the histories of these peoples, sometimes in remarkable detail.

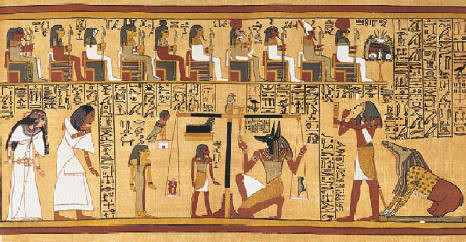

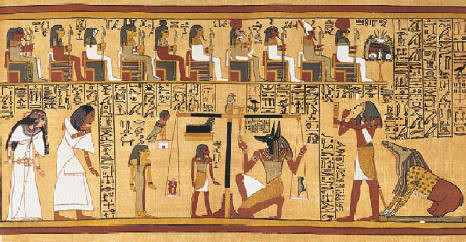

For one to consider himself or herself literate in the field of

such research, there are several works that must be read and considered as a collective whole for scholarship and understanding: Gilgamesh,

The

Egyptian Book of the Dead, the Hebrew Scriptures, and the Dead Sea

Scrolls (what we know of them, at least--the Israelite government and its

scholars have been loathe to share the material, to the extent that some have

secretly "stolen" the documents by recording them illegally and making them

known in the West, which has only increased the heightened value of the scrolls

and what they say--perhaps unnecessarily.

The

Egyptian Book of the Dead, the Hebrew Scriptures, and the Dead Sea

Scrolls (what we know of them, at least--the Israelite government and its

scholars have been loathe to share the material, to the extent that some have

secretly "stolen" the documents by recording them illegally and making them

known in the West, which has only increased the heightened value of the scrolls

and what they say--perhaps unnecessarily.

However, it cannot be emphasized enough that several works of that part of the

world, written within several centuries of one another (a glance in time for

those eras), must be considered as parallel thought and influence upon kingdoms

and ancient homelands that impacted upon one another.

For instance, what did Joseph bring to the history of the twelve tribes by his time in Egypt? How did familiarity with the Egyptian deities and

way of life influence the people who joined Moses in their exodus from that part of the world? What did they know of Canaan? And

certainly, the Jews in Babylonian "captivity," where the Babylonians moved the best families and government officials to Babylon after their

capture of Israel, must have picked up something of their Babylonian lords in the five hundred years of bondage. When we see the Enuma

Elish, the Babylonian view of Creation, we must be influenced, seeing the two versions of how the world began and in what order; they're so closely

similar that even the precise events become mirrored. How much did the Babylonians influence the Hebraic version of "history," given

that for half a millennium they lived in a land not their own and remembered through oral history the place they had originated and were to call

"home."

Some of the most amazing discoveries have been textual ones, which above we described

as "archaeological" ones. The Rosetta stone discovered in 1801 provided the key to deciphering hieroglyphics. This opened up for

interpretation the vast library of inscriptions, letters and texts from Egypt--the home of Joseph, and his ancestors, whom the deliverer Moses would

take from their "homes" for a promised land of milk, honey, and the voice of their God. They struggled for forty years in that

"wilderness" of neither/nor: not Egypt, and certainly not the Promised Land. Sigmund Freud advanced the thesis that the real Moses was,

indeed, killed by his people in that wilderness period; but they, feeling guilt for their murder of the Father figure, invented a new tale, one in

which they revolted but were "put down" by their savior and found the land which they sought.

This, of course, figures prominently in

Freud's Oedipus Complex, in which all children desire and then feel guilt about wishing the father-figure dead. But theories aside, the

artifacts, such as Gilgamesh or the Dead Sea Scrolls, stand for only two of several recent finds: The Ebla tablets from Syria, dating as

early as the third millennium B.C.E., even now being translated and published, are increasing our

knowledge of Semitic civilizations in western Mesopotamia and Syria. Other texts, artifacts, and building structures from Ugarit, Mari, Nuzi, Nippur,

and many other sites enable us to reconstruct the context for the Hebrew Bible. Some of these discoveries will be described in more detail as they are

relevant to the interpretation of specific texts.

The Hebrew Bible is itself the major source for the writing of Israelite history,

containing most of the information we have available concerning the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. It has virtually the only information available

about the ancestors of Israel. But we have to remember that we cannot read the Hebrew Bible as a straight record of events. It is first and

foremost a literary and theological creation that was profoundly shaped by the religious and social world of the writers. While it contains records of

certain events, it is not first of all historiography. In other words, it was not intended to be a chronicle of events as they happened, such as

modern scientifically researched works of history are. Consequently, it can provide some historical information, but it is not, strictly

speaking, history. And now, we're back into the area of Joseph Campbell or Northrop Frye: we speak of primitive associations, myth-making, and, literarily

speaking, of metaphors and their prominence in explaining the inexplicable to a people.

Unfortunately, today we underestimate (and I believe

misunderstand, at best) the power of literary tropes, of metaphors, of analogies, and all the things that raise the blood pressure of those seeking

"literal" interpretations of things. If nothing else, we need to learn that metaphors and figurative language are far superior to the

literal, because they don't merely describe, as the literal does, but capture the essence, feeling, heart, suggestion, and personal interpretation of

what we describe or give "evidence" to. Those who underestimate metaphors have never read the parables of Jesus, or, at the best, have

misunderstood them. Can you imagine NOT understanding the power of metaphors when reading the parables? And if some accounts are

metaphors, and other literal, how does one differentiate? What guide says, "this is figurative, but this is literal--please see the

difference." The Apostle Paul weighed in on this argument, maintaining that the Abraham/Sarah accounts were figurative--so, do you know

where, the context, or implication for the statement?

And, for those wondering why we call the land of the Hebrews Canaan, "Promised

Land," Israel, Palestine, or even Judah, we offer:

|

The terms that apply to the territory of Israel's existence are varied. The name Canaan

occurs in Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Phoenician writings beginning around the fifteenth century

B.C.E. as well as in

the Bible. It refers sometimes to an area encompassing all of Palestine and Syria, and sometimes includes the entire land west of the

Jordan River. The term may derive from a Semitic word meaning "reddish purple," referring either to the rich dye produced in

the area or to wool colored with the dye.

The name Palestine refers to the area from the Mediterranean coast to the Jordan valley and from the southern

Negev to the Galilee lake region in the north. The term derives from the Hebrew word

peleshet, the land of the Philistines. After

the second Jewish revolt (132-135 C.E.) the Romans adopted the name Palaestina for this territory.

The name Palestine was revived after World War I and applied to this territory under the British Mandate. Today it has been adopted as

the name of the political entity of Arab people living in this region. The name Israel comes from Hebrew

Bible usage, and refers both to geographical territory (erets yisrael, the land of Israel) and the nation state that dwelled there. Its

biblical origin is the name God gave to Jacob after they wrestled (see

Genesis 32:29);

yisrael

means "strives with God" or "God strives." This land is also termed "the Promised Land" in the

belief that Israel's possession of the land was a divine gift. Pilgrims and the devout also refer to it as "the Holy Land," in

recognition of its associations with biblical saints and religious leaders. Now, associate what you've read above with America--it's not

a stretch--and try to understand why America had been referred to the "New Promised Land," etc.

The attempt to find

association in God's message with historical events has dated from the first writings (even oral history) of the Hebrew people until the

settlement of America. And, when pressed by conservative, political interpreters of America's role in the world, we find that Israel's

justification for the seizure and settlement of Cannan territory set a precedent for believers in a new "Promised Land." Thus

began America's difficulties with those who saw prophecy or God-ordained precedence with others who believed that the unknown world was

settled by the righteous, Western believers of their own interpretation of biblical history, anagogical promise, and prophetic fulfillment.

|

For the “New Testament” or Christian Writings,

there exists a different focus than the telling of a people: we have the

spiritual journey of an individual, one who taught, chose his followers,

healed, claimed a special relationship with God (and this, again, depends on a

close reading of the Gospels—remember “facticity”), was traitorously led

to his death, fulfilled prophecy, and then arose from the grave.

And, in keeping with the idea of “authorization,” the earliest work

of this New Covenant was undoubtedly a letter by one of his followers to a group

concerning their common beliefs regarding the One.

Even more interesting is that the followers and writers were the Jews who

derived from those who believed in, accepted, and well understood the writings

equated with the “Old Testament.”

The King James Version

lists twenty-seven books (a

loose term, since some of these recorded the events of Joshua’s life, some the

acts of his followers following his death, others recorded as letters to

struggling, infant congregants of the “Chosen,” and one work that nearly

defies description, alternately described as prophecy, coded-allegory, defiance,

or a belief that the “Last Days” were upon them.

These works are grouped as:

|

The Gospels (“Good News”):

Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John (though not written in that order, and

the last takes exception with the former three).

|

|

The Epistles (letters to the young Church [the

“called out”]): Romans, Corinthian Church (I and II), Galatians,

Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, the Church at Thessalonia (I and II),

Timothy (I and II), Titus, Philemon, Hebrews, James (I and II), Peter (I,

II, III), John, and Jude. |

|

The Apocalypse (Revelation of John—though the

authorship is in question; moreover, we should note that “Apocalypse”

has various meanings for us today: “final days,” “revelation,”

“vision, or things to come”). |

All of the events in all of these works take place,

for the most part, in a relatively small area of the world, equivalent to a

middle-size state on the Eastern Coast of America.

Benson Landis, author of An Outline of the Bible Book by Book , and from whom I derive a much

condensed background view that I appreciate, given my tendency toward wordiness

and an inability to omit the inconsequential) notes that the largest territorial

control of these formerly nomadic people existed during the reins of King David

and his son, the king Solomon, from about 1000 BCE to 900 BCE, having a

population under two million people (by way of comparison, more than seven

million people use city transportation in Manhattan every day).

In other words, who would have thought that such a minority would leave

such a lasting impression on the world? Remember

this time-frame, for this is when the earliest writings of the Hebrew people

probably “authorized” their beginnings, gave allegiance to one god, and set

forth the resulting laws.

So why is all of this background information

important? We study the narratives

of selected books of what came to be known by the collective name, The Bible.

It matters not whether one sees these stories as part of a divine plan or

not. Anyone may study them as

literature. And literature, we

should note, has acquired bad press, so to speak, as to its present-day meaning.

We seem to accept that literature means “fiction,” and even

that term, we should dispute, has come to mean something akin to “untrue.”

It was not until the eighteenth century that the term

literature began to take on its present meaning.

At one time, anything that was written was deemed literature.

We still use the term when we refer to factual arguments when we ask,

“and what does the literature say on this subject?”

Law, philosophy, religion, stories, exemplum, bawdy tales, and anything

written once broadly designated literature.

Only recently have we used the term to denote something other than true.

Yet anyone who has studied literature knows that truth exists in the most

outrageous of tales, anticipating, reporting, sensing, describing, enduring, or

regretting all the emotions and feelings of individuals, whether writ large or

small. If you want to know a

people, study literature; if you want to study latent observations about

these people, then history is for you.

In studying Genesis, we find evidence of several

writers. Yet, bring this to the

attention of those who don’t view the Hebrew Scriptures as narratives and they

bolt—or turn angry and defiant. A

sufficient answer should consist of in some form, “but the Gospels tell the

story of the life of Jesus from differing perspectives; why do you think that

Genesis cannot be an equivalent story of how these people came to be and how

they came to believe in one god as opposed to many?” So too, students will—due to the familiarity and bias that

originates in early childhood—fail to apprehend the differing levels of

intended emotional reaction in Genesis.

God

did not, apparently, develop a sense of humor or irony until the Christian era.

One of the finest examples of typical humanity and its funniest

attributes must surely be when Yaweh questions Adam as to why he ate of the

forbidden fruit: Three are lined up, as Yaweh first goes to Adam, who passes the

blame to Eve, who passes the blame to the Serpent, who passes the blame

to…damn! “Thanks a lot guys; I open your eyes, introduce you to

maturity, give you a real treat, and this is my thanks? You leave me hanging….”

That’s human nature, with all its foibles, its silliness, and its

reactions, like a child caught in the act but with other children to blame.

The Bible, therefore, represents an amalgam of the

explanations, deeds, recollections, expressions, and failures of a people.

Some speak directly to us, others speak about what is to come, some blame

the past, some look to the future, but all remain human, with tales to

tell and experiences to relate. And

we should study them in the same spirit and joy as in reading a work that speaks

directly to us, as if the author had us in mind when the work was penned.

Whether faithful believer, one who acknowledges the importance if not the

exactitude, or as an unbeliever who can still appreciate the beauty of

expression, the Bible stands as the most influential work in Western

civilization.

Shakespeare drew upon

it, as did Nathaniel Hawthorne, who showed his embarrassment in both his lost

belief and hatred for his Puritan ancestry, as did Gore Vidal, whose Julian

the Apostate celebrates the last of the Common Era Caesars who wished to

return to the gods of the past, or Norman Mailer or Christopher Moore, both of

whom give us informative if human Jesus’, who break down our conceptions of a

Messiah who neither laughed, wondered about lust, or enjoyed his humanity yet

feared its end.

The Bible remains, then, a collection of stories that

we can identify with, cry over, laugh with, become intrigued, feel anxiety

about, wonder over, or, quite simply, enjoy.

Taking the work as a guide to salvation does not diminish its power as

literature. For some, that’s an

added bonus; for others, it’s sufficient enough for reading, enjoying, and

profiting.

Time Consideration:

B.C.E. refers to dates Before the Common Era, what

used to be called B.C. (Before Christ).

C.E.

refers to dates of the Common Era, what used to be called

A.D. (anno domini,

in the year of our Lord). This change in terminology has been developed to divest the dating scheme

of sectarian religious associations.

Remember that year dates and century dates run in reverse in B.C.E.

For example, the ninth century B.C.E. is the 800s, and 850

B.C.E. is

earlier than 800 B.C.E. A millennium is a thousand year period. When talking about

large blocks of time, this term is sometimes used. There are many competing systems of dates for Old

Testament events and the reigns of kings. We follow the widely used chronology of

Bright

(1981).

Judaism has a tradition of counting years from the day of creation as determined

by biblical chronology. In this tradition creation happened on October 7, 3761

B.C.E.

of the Gregorian calendar. Years are designated A.M. for anno mundi, year of

the world. Islam dates years beginning with the hijrah (which is the year 622 of the Western

calendar).

Considering a Time Frame:

Archaeological Periods

| Pre-Pottery Neolithic A |

8500-7500 B.C.E. |

| Pre-Pottery Neolithic B |

7500-6000 B.C.E. |

| Pottery Neolithic A |

6000-5000 B.C.E. |

| Pottery Neolithic B |

5000-4300 B.C.E. |

| Chalcolithic |

4300-3300 B.C.E. |

| Early Bronze I |

3300-3050 B.C.E. |

| Early Bronze II-III |

3050-2300 B.C.E. |

| Early Bronze IV/Middle Bronze I |

2300-2000 B.C.E. |

| Middle Bronze IIA |

2000-1800/1750 B.C.E. |

| Middle Bronze IIB-C |

1800/1750-1550 B.C.E. |

| Late Bronze I |

1550-1400 B.C.E. |

| Late Bronze IIA-B |

1400-1200 B.C.E. |

| Iron IA |

1200-1150 B.C.E. |

| Iron IB |

1150-1000 B.C.E. |

| Iron IIA |

1000-925 B.C.E. |

| Iron IIB |

925-720 B.C.E. |

| Iron IIC |

720-586 B.C.E. |

Forms of Analysis:

A. Literary Analysis

The literary material of the Hebrew Bible is some of the most ancient of the Western literary

tradition, but this does not mean it is primitive or artless. Its writers were often masterful in

utilizing a rich repertoire of literary techniques, including hyperbole, metaphor, symbolism,

allegory, personification, irony, wordplay, and parallelism.

Conventions differ depending on the type of literature, so we will need to

develop a sensitivity to different types and styles of writing. For example, writing styles and

reader expectations for historical narrative differ considerably from those of poetic hymns, and

these in turn are different from the conventions of apocalyptic literature. Each type of literature,

such as those just mentioned, is called a genre. The major genres found

in the Hebrew Bible include narrative, prophecy, law, hymn, proverb, chronicle, and genealogy. We

have to be become "literarily literate" and alert to the conventions of these genres

B. Historical Analysis

Because the origin of the Hebrew Bible is far distant from us, we will need to recover the

original historical and geographical setting of the Hebrew Bible in order to understand and

appreciate it. In so far as we are able, we must to try to see the world as David, Isaiah, and Ezra

saw it. Though not an easy job, it is a rewarding one. To do so we will draw upon the discoveries of

generations of historians, archaeologists, and biblical scholars.

The history of Israel is intertwined with the histories of many ancient nations.

In Mesopotamia, the Sumerians pioneered civilization and were followed by Babylonians, Assyrians, Hurrians, Amorites, and Arameans. In addition, the Egyptians, Hittites, Phoenicians, and Philistines

interacted with Israel and were significant factors in determining the directions Israel's history

was to take. Historians, on the basis of ancient documents and archaeological discoveries, have been

able to reconstruct the histories of these peoples, sometimes in remarkable detail.

Some of the most amazing discoveries have been textual ones. The Rosetta stone

discovered in 1801 provided the key to deciphering hieroglyphics. This opened up for interpretation

the vast library of inscriptions, letters and texts from Egypt. The Ebla tablets from Syria, dating

as early as the third millennium B.C.E., even now being translated and published, are

increasing our knowledge of Semitic civilizations in western Mesopotamia and Syria. Other texts,

artifacts, and building structures from Ugarit, Mari, Nuzi, Nippur, and many other sites enable us

to reconstruct the context for the Hebrew Bible. Some of these discoveries will be described in more

detail as they are relevant to the interpretation of specific texts.

The Hebrew Bible is itself the major source

for the writing of Israelite history. It contains most of the information we

have available concerning the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. It has virtually the

only information available about the ancestors of Israel. But we have to

remember that we cannot read the Hebrew Bible as a straight record of events. It

is first and foremost a literary and theological creation that was profoundly

shaped by the religious and social world of the writers. While it contains

records of certain events, it is not first of all historiography. In other

words, it was not intended to be a chronicle of events as they happened, such as

modern scientifically researched works of history are. Consequently, it can

provide some historical information, but it is not, strictly speaking, history.

C. Tradition Analysis

The text of the Hebrew Bible contains the record of Israel's faith journey and its application of

tradition to life. As Israel faced new historical challenges it took the faith expressions of its

ancestors and reapplied them anew. Its literature is the product of a God-fearing community. The

people who wrote the books of the Bible composed them as the expression of their faith and because

they believed these writings might inspire faith, courage, and understanding.

Most of the books arose at important turning points in Israel's national life.

The community grounded its experience of God in their history, and believed that his commitment to

them provided a certain measure of security in a threatening world. But their world never stayed the

same. Empires rose and empires fell, and Israel had to adapt to the changing political and social

environment. Part of the adaptation was applying the traditional promises of God to an uncertain

future. From Torah to Writings, the text reveals the community's record of how they heard God

speaking to them.

The Hebrew Bible is the record of a creative tension between religious tradition

and the need for change. Earlier forms of tradition were embodied in early documents and we can

reconstruct and examine them. These earlier documents defined truth for the community that produced

them. They provided the people with religious and ideological stability, a way to understand God and

his ways. But as history moved on, new interpretations and applications were needed.

These texts encapsulate a long and lively dance of interpretation and

reinterpretation, the written expression of a conversation which took place over a period of a

thousand years. Political and social changes within the community inspired the need for new

interpretations and applications of the older authoritative texts. The older texts provided the

foundation for the life of the community, and allowed for stability in the midst of changed

circumstances.

Part of what we mean by tradition analysis is reading the text as the record of

the faith of a community that was defined by its theological traditions and took its traditions

seriously. Those traditions were authoritative, and the community depended on them as they faced the

future. Old and new, stability and change, tradition and innovation, text and

reinterpretation--these are the parameters that will order our reading of the theology of the Hebrew

Bible. We will be "tradition archaeologists" as we peel away the strata of this dialectic

between tradition and change, and in the process perhaps learn how tradition can help us face the

future.

The People:

It is important to use terms appropriately when referring to biblical people. Before Israel

became a nation its ancestors would not have been called Israelites. Properly speaking, the

ancestors were Hebrew. The term Israelite

should be reserved for the people of God from the time of Moses until the time of the exile. The

term Jew should be reserved for the descendants of the Israelites

beginning with the period after the Babylonian exile of the sixth century

B.C.E. when

Judaism emerged. The term derives from the name of the tribe of Judah, the only tribe to survive

destruction, and still applies to the descendants of Judah today. The term

Israeli

should not be applied to any biblical people. It refers to citizens of the modern state of Israel,

founded in 1948

The Land:

The terms that apply to the territory of Israel's existence are varied. The name Canaan

occurs in Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Phoenician writings beginning around the fifteenth century

B.C.E.

as well as in the Bible. It refers sometimes to an area encompassing all of Palestine and Syria, and

sometimes includes the entire land west of the Jordan River. The term may derive from a Semitic word

meaning "reddish purple," referring either to the rich dye produced in the area or to wool

colored with the dye.

The name Palestine refers to the area from the

Mediterranean coast to the Jordan valley and from the southern Negev to the Galilee lake region in

the north. The term derives from the Hebrew word peleshet, the land of the Philistines. After

the second Jewish revolt (132-135 C.E.) the Romans adopted the name Palaestina

for this territory. The name Palestine was revived after World War I and applied to this territory

under the British Mandate. Today it has been adopted as the name of the political entity of Arab

people living in this region.

The name Israel comes from Hebrew Bible usage, and

refers both to geographical territory (erets yisrael, the land of Israel) and the nation

state that dwelled there. Its biblical origin is the name God gave to Jacob after they wrestled (see

Genesis 32:29); yisrael means "strives

with God" or "God strives." This land is also termed "the Promised Land" in

the belief that Israel's possession of the land was a divine gift. Pilgrims and the devout also

refer to it as "the Holy Land," in recognition of its associations with biblical saints

and religious leaders.

Israel existed both historically and geographically within the context of a larger region.

When authorities refer to the old world they call it the ancient Near East. When they refer to

current events in that same region they call it the Middle East. Most refer to the area

as the ancient Middle East to reinforce the reality that the ancient events of biblical history

occurred in the same place we have come to know from our exposure to modern politics in the news.

Within the ancient Middle East there are other applicable terms. Mesopotamia,

literally "between rivers," is the land between the Tigris River and the Euphrates River.

It was home to the great Sumerian, Babylonian, and Assyrian civilizations, and is today roughly

coterminous with Iraq.

The term Fertile Crescent refers to the

half-moon-shaped inhabitable area of the ancient Middle East where civilizations thrived. This

general area, in which Israel was located, has a rich and venerable history, and generated extensive

literary and religious traditions.

The term "Fertile Crescent" was popularized by the

American Orientalist James Henry Breasted (1865-1935).

Divine Names:

The treatment of the divine name in English translations of the Hebrew Bible and in this textbook

needs to be explained. The God of Israel was referred to in various ways. Sometimes God was just

"God," or elohim in Hebrew. When you see "God" in the text, this

typically trans Elohim. Other times God is referred to by his personal name, YHWH. It is rendered

Yahweh in some versions, and the LORD in others. The letters "ORD"

in LORD are in smaller-sized capital letters to distinguish it from the divine title

"the Lord." Most modern translations of the Hebrew Bible employ this typographic

convention to indicate when YHWH is the underlying Hebrew text.

The four consonant divine name YHWH is referred to as the tetragrammaton. When the Hebrew text

refers to Yahweh it uses the four consonants YHWH with a special configuration of vowels to signal

that it should not be pronounced out loud to guard the sanctity of God's name. If the divine name is

never spoken it can never be taken in vain. The name Yahweh, or Jehovah in its older pronunciation,

is never spoken in Judaic contexts. In Jewish tradition the words "the LORD,"

adonay in Hebrew, are substituted for YHWH. In addition to the extensively employed terms Elohim

and Yahweh, the Hebrew Bible uses other divine names such as El Shaddai and El

Elyon.

which undoubtedly proves equally true.

The literary critic Harold Bloom has a term for those works, events, or

passages in literature which we believe we know, but when read closely (often

for the first time) turn out to be different than what we’ve been led to

believe: he calls such things a “facticity.”

This cumbersome word manifests what most people, who would swear

otherwise (ironically on a stack of unread Bibles), deny.

But how well do we know what the Bible says, whether we believe it to be

the word of God or not?

which undoubtedly proves equally true.

The literary critic Harold Bloom has a term for those works, events, or

passages in literature which we believe we know, but when read closely (often

for the first time) turn out to be different than what we’ve been led to

believe: he calls such things a “facticity.”

This cumbersome word manifests what most people, who would swear

otherwise (ironically on a stack of unread Bibles), deny.

But how well do we know what the Bible says, whether we believe it to be

the word of God or not?

The

Egyptian Book of the Dead, the Hebrew Scriptures, and the Dead Sea

Scrolls (what we know of them, at least--the Israelite government and its

scholars have been loathe to share the material, to the extent that some have

secretly "stolen" the documents by recording them illegally and making them

known in the West, which has only increased the heightened value of the scrolls

and what they say--perhaps unnecessarily.

The

Egyptian Book of the Dead, the Hebrew Scriptures, and the Dead Sea

Scrolls (what we know of them, at least--the Israelite government and its

scholars have been loathe to share the material, to the extent that some have

secretly "stolen" the documents by recording them illegally and making them

known in the West, which has only increased the heightened value of the scrolls

and what they say--perhaps unnecessarily.