It became a Mithraic, and finally a Christian, holy day.]

Daily sacrifice was offered at the altar of Mithras, the worshipers partook of consecrated bread and wine, and the climax of the ceremony was signaled by the sounding of a bell.

It became a Mithraic, and finally a Christian, holy day.]

Daily sacrifice was offered at the altar of Mithras, the worshipers partook of consecrated bread and wine, and the climax of the ceremony was signaled by the sounding of a bell.

Mythology and its Definitions

Mythology Ceremonies of various cults were to be seen throughout the Roman, Greek, and Mideast in which gods were celebrated for having lived, suffered agony, died, and then resurrected. In Syria, the god Tammuz was heralded with the cry "Adonis [i.e., the Lord] is risen," and his ascension into heaven was celebrated in the closing scenes of his festival. Similar ceremonies commemorated in Greek ritual the agony, death, and resurrection of Dionysus.

From Cappadocia the worship of the goddess Ma had spread into Ionia and Italy; her priests (called fanatici as belonging to the fanum, or temple) danced dizzily to the sound of trumpets and drums, slashed themselves with knives, and sprinkled the goddess and her devotees with their blood. The worship of Cybele held its ground throughout Africa, Italy, Lydia, and Phrygia. At her spring festival, priests bore the young god Attis, her beloved, to his grave and later celebrated his resurrection. He was said to have died for the people's salvation.

On the day of the feast an image of the Great Mother was carried in triumph through crowds that hailed her as Nostra Domina, "Our Mother." Even more widely honored than Cybele was the Egyptian goddess Isis, the sorrowing mother, the loving comforter, the bearer of the gift of eternal life. Her great spouse Osiris had died and had risen form the dead. Isis was pictured as holding her child Horus in her arms, and devout litanies hailed her as "Queen of Heaven," "Star of the Sea," and "Mother of God." The religion of Isis spread in the fourth century B.C.E. to Greece, to Sicily in the third, and then into all parts of the Empire.

The followers confessed their sins, abstained from certain foods for a time, bathed in the bay for spiritual cleansing, and then offered sacrifice -- usually a pig. For three days at the Feast of Demeter, the initiates mourned with her the snatching of her daughter into Hades, and meanwhile lived on consecrated cakes and a mystic mixture of flour, water, and mint. Meanwhile the Persian masculine cult of Mithras was passing from Persia to the most distant of the Roman frontiers. He too was the god of light. In Zoroastian [after the Greek; the Persians called the god Zarathustra] theology, Mithras was purity, truth, and honor; sometimes he was associated with the sun and led the cosmic war against the powers of darkness, always he mediated between his father and his followers, protecting and encouraging them in life's struggle with evil, lies, uncleanliness, and the other works of Ahriman, Prince of Darkness.

He lived the exemplary life, was crucified for his goodness, and rose after three days to ascend to heaven.

When Pompey's soldiers brought this religion from Cappadocia to Europe a Greek artist pictured Mithras as kneeling on the back of a bull and plunging a poniard into its neck; this representation became the universal symbol of faith. The seventh day of each week was held sacred to the sun-god; and towards the end of December his followers celebrated the birthday of Mithras "the Invincible Sun," who, at the winter solstice, had won his annual victory over the forces of darkness, and day by day would now give longer light. [Christmas was originally a solar festival, celebrating, at the winter solstice, about December 22nd, the lengthening of the day and triumph of the sun over his enemies.

It became a Mithraic, and finally a Christian, holy day.]

Daily sacrifice was offered at the altar of Mithras, the worshipers partook of consecrated bread and wine, and the climax of the ceremony was signaled by the sounding of a bell.

It became a Mithraic, and finally a Christian, holy day.]

Daily sacrifice was offered at the altar of Mithras, the worshipers partook of consecrated bread and wine, and the climax of the ceremony was signaled by the sounding of a bell.

(The god, Mithras, whose life, death, and resurrection compares to Christianity)

The followers of Mithras pledged a lifelong pursuit of good against evil. After death, said its priests, all men must appear before the judgment seat of Mithras; then unclean souls would be handed over to Ahriman for eternal torment, while the pure would rise through seven spheres, shedding some mortal element at each stage, until they would be received into the full radiance of heaven by Ahura-Mazda himself. Zoroasters' conception was divine. A guardian angel picked out a priest; at the same time, a virgin of noble birth was imprisoned by a ray and Zarathustra began to be. The priest married her, and she gave divine birth.

He was known for his wisdom and righteousness, and he withdrew from society to live in the wilderness where the Devil tempted him, but to no avail. He suffered for his faith, at one point having his breast pierced with a sword, but he lived to an old age and was consumed in a flash of lightning and ascended to heaven. Mithras was a pre-Zoroastrian god, along with Anaita, goddess of fertility and earth, and Haoma the bull-god, who dying, rose again, and gave mankind his blood as a drink that would confer immortality. Zarathustra was shocked at these primitive deities; he rebelled and announced the one God -- her Ahura-Mazda, the Lord of Light and Heaven, of whom all other gods were but manifestations and qualities.

Such events and stories speak of a cultural unity for humanity; we find such themes as the fire-theft, deluge, land of the dead, virgin birth, and resurrected hero worldwide. All peoples have elements or combinations of such events, whether for entertainment or as religious mysteries. The progress of humanity has not only been that of the toolmaker, but a history of the attempts at extreme costs to gain converts to its covenants. Humanity, apparently, cannot maintain itself in the universe without the belief in some arrangement of the general inheritance of myth.

Mythology is not a matter of the archaic or of no moment to modern people. Its symbols tough and release the deepest centers of motivation, moving literate and illiterate alike, moving mobs, and moving civilization. Huizinga argued that in the underlying consciousness of things "not being real" the beginning point is the fun of play, a fanciful spirit of play on the border-line between jest and earnest. In the mind of the good player it is possible to imagine that everything has become the body of a god, or reveals the omnipresence of God as the ground of all being. In such games, it is possible to also imagine that other spheres contain a reality that we are only playing at in our own imaginations.

To fall from the game, caused by life or by the gods, must represent the vulgarization of play -- a fall or spiritual lapse. In playing the game of "what if," we shed the reasonableness that exists only so far as our own limited consciousness and move toward the transcendent, toward belief. Animals can know fear at birth and instinctually fear their predators; children can invent games of witches or demons, or fear the unknown in terms of a horrible monster. Are these instincts inherited images?

Humans have, of course, responses that are instinctual: the child reaching for the nipple, sexual desire when hormones release chemical agents -- humans are anything but the tabula rasa of seventeenth-century epistemology. James Joyce, in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, supplies an excellent structuring principle for a cross-cultural study of mythology when he defines the material of tragedy as "whatsoever is grave and constant in human sufferings." For it is from the "grave and constant" that the imprints common to the mythologies of the world must be derived.

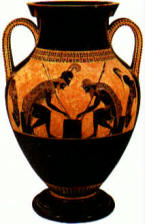

Greek tragedy was a poetic inflection of mythology, the tragic catharsis of emotion through pity and terror of which Aristotle wrote being precisely the counterpart, psychologically, of the purgation of spirit -- catharsis -- effected by a rite. Like the rite, tragedy transmutes suffering into rapture by altering the focus of the mind. The tragic art is a correlate of the "spiritual cleansing," or the "stripping of the self." One is united in tragic pity with "the human sufferer" and in tragic terror with "the secret cause," Plato's "likeness of that which intelligence discerns." When we can leave humanity and reason behind, we become one with the great "otherness": where tragedy ends, comedy begins, and the mode of tragedy dissolves and the myth begins.

Mythology is a rendition of forms through which the formless Form of forms can be known. An inferior object is presented as the representation, or habitation, of a superior. The love attachment felt for the inferior is a function actually of one's potential establishment in the superior; yet it must be sacrificed (therein the suffering) if the mind is to pass on to its proper end. Mythology is a study of the deceptive attributes of being, through which the human mind, in the various eras and areas of its domain, has been united with the secret cause in tragic terror, and with the human sufferer (the self being stripped away) in tragic pity.

These beliefs can be of two sources: the arena of the human condition or particular to a given area. There are forces that are constant to humanity: gravity, for instance, and its affects on the conditional form of the body and all its organs; the diurnal alteration of light and dark; the mind plunged into dream and its differences from the logic of wakefulness. Others abound: the universe and its rotational logic; the moon's death and resurrection; the differences in physical structure between the sexes and their attraction. Nature is violent. There is in nature and there subsists in man a movement that always exceeds the bounds, which can never be anything but partially reduced to order.

We are conscious of being in its power: the universe that bears us along answers no purpose that reason defines, and if we try to make it answer to God, all we are dong is associating irrationally the infinite excess in the presence of which our reason exists with our reason itself. God exceeds the limits of reason. Work produces a relaxation of tension; it collectivizes us and helps us oppose the contagious impulses toward excess and toward violence. Hence, the human collective, partly dedicated to work, is defined by taboos without which it would not have become the world of work that it essentially is. Violence is what the world of work excludes with its taboos; the two primary taboos affect, firstly, death, and secondly, sexual functions.

Death for the earliest of humans was terrifying and overwhelming, and indeed supernatural. Burial of the dead first appears toward the end of the Middle Paleolithic era, a little while before the disappearance of Neanderthal man and the arrival of a man exactly like us. The corpse is an image of destiny for us. Death is disorder, an absence of all that communal existence strives for. Burial was no doubt signified from the earliest times as a wish to save the dead from the voracity or animals. Although motionless, the dead man also had a hand in the violence that destroyed him; anything which came too near him was threatened by the destruction which had brought him low. Death is a danger for those left behind. If they have to bury the corpse it is less in order to keep it safe than to keep themselves safe from its contagion.

The corpse will rot; this biological disorder, like the newly dead body a symbol of destiny, is threatening in itself. So too, the violence attendant upon a man's death is only likely to tempt men in one direction: it may tend to be embodied in us against another living person -- the desire to kill may take hold of us. But taboos founded on terror are not only there to be obeyed. There is always a temptation to knock down a barrier; the forbidden action takes on a significance that is invested with an aura of excitement. Sexual activity is also a form of violence because it is an impulse that can interfere with work. From the beginning, sexual liberty must have received some check which we are bound to call a taboo.

But here it becomes apparent that we cannot isolate a particular taboo, such as incest, on a universal basis. Taboos spring from a horror of violence; for instance,

the taboos associated with menstruation and the loss of blood at childbirth, which are thought of as manifestations of internal violence and the accompanying suggestion of degradation.

We refuse to see that life is the trap set for the balanced order, that life is nothing but instability and dis-equilibrium.

the taboos associated with menstruation and the loss of blood at childbirth, which are thought of as manifestations of internal violence and the accompanying suggestion of degradation.

We refuse to see that life is the trap set for the balanced order, that life is nothing but instability and dis-equilibrium.

Life is a swelling tumult continuously on the verge of explosion. But since the incessant explosion constantly exhausts its resources, it can only proceed under one condition: that beings given life whose explosive force is exhausted shall make room for fresh beings coming into the cycle with renewed vigor. Human life strives towards prodigality to the point of anguish, to the point where the anguish becomes unbearable. We squander energy in living, but at bottom we all want the impossible situation it all leads to: the isolation, the threat of pain, the horror of annihilation. Our judgments are formed under the influence of recurring disappointments and the obstinate expectation of a clam which goes hand in hand with that desire.

Sexuality and death are simply the culminating points of the holiday, nature celebrates, with the inexhaustible multitude of living beings, both of them signifying the boundless wastage of nature's resources as opposed to the urge to live on characteristic of every living creature. Humanity is discontinuous; we live in isolation of ourselves even in the group. Only in intercourse and in death do we achieve the continuity that we long for. Logoi, which can refer to several kinds of discourse, includes mythos. The two are in fact interchangeable synonyms for "story" until Plato reorganizes the semantic of these words, with the result that mythos is opposed to logos in the senses both of verifiable discourse and of argumentative discourse.

Myths are never neutral but always have some point in the context in which they are told, and thus in principle they demand an answer. The now current definition of myth is "traditional tale," provided that the difficult word "traditional" means "without an identifiable author." The "Cambridge School" is associated with the idea of linking myth and ritual; these scholars drew their inspiration from Sir James Frazer's The Golden Bough. Myth was the dominant factor in nineteenth century studies of the history of religion until a change took place somewhere in the last quarter of the century.

Textbooks that nowadays would carry "history of religion" in the titles were then classified regularly as mythology. Ritual dominates the scene in practically all the textbooks on Greek and Roman religion during most of the twentieth century. How and when did the idea arise that myth and ritual might be closely related? W. Robertson Smith introduced the well-known theory of sacrifice. In his view, sacrifice as communion -- man shares in the vital force of the consumed animal -- acquires an additional mythical dimension: as a totem, the sacrificial animal is raised to divine status, so that myth arises from a social rite. Smith pointed out the road taken by his student and friend James Frazer.

Just as nature goes through an annual cycle of budding, flowering, bearing fruit, withering and dying, so each year the "aged" king had to be supplanted by a new vigorous successor, for it is the king's magic power that sympathetically influences and even controls vegetative life. Nature's death has to be overcome by a new, young king who defeats the old one in a ritual fight -- or somehow supplants him. There is also a mythical representation or transposition of the natural cycle, dealt with by Frazer in other parts of his series, originally published as a separate volume. A great many cultures, notably those of ht Mediterranean world and the Near East, have their "dying and rising gods."

They represent grain, green plants, and trees. Their myths tell of menace, downfall, sojourn in the underworld, and death, but also of resurrection. During the annual New Year festivities lamentations are heard bewailing the god who has died, but it is not long before they are replaced by hilarious joy: the god has risen or has manifested himself again, heralding a promise of new life. There thus emerges an almost ideal parallelism of myth and ritual, both reacting to or reflecting the vegetative cycle of nature: Rite Myth 1) Sacral year king guarantees Year god represents fertility of nature; natural vegetative force; suffers ritual death; dies, is imprisoned in underworld; a new, vigorous king succeeds rises again, is reborn.

This scheme is a fundamental one: it is invoked by all myth and ritual theories of the first phase. Jane Harrison was a member of the Cambridge school: known as "Bloody Jane" to friends, she was a student of Robertson and Frazer, who was known for her libertinism in matters of sex and religion, though no doubt brilliant and vastly knowledgeable on Greek material. Her life is often more the focus for inquiry than her works; still, though they have been forgotten while Robertson's and Frazer's continue, this is somewhat unfair. In her view myths were created in order to account for rites.

The gods are supposed to belong to the domain of myth. They arise as a kind of personification from rites, especially apotropaic ones, meant to protect crops and settlements. In her work Themis, there is a sudden, strong emphasis on the social component of the myth-making process: "Strong emotion collectively experienced begets this illusion of objective reality; each worshipper is conscious of something in his emotion not himself, stronger than himself. He does not know it is the force of collective suggestion, he calls it a god." In the Frazerian scheme, man is the manipulator: he believes he can control external processes by means of specific, above all magical, methods -- rites.

Myth, then, is a kind of verbal account of these rituals. In the new interpretation, on the other hand, man is the one who is manipulated: however the ritual may relate to external data like fertility of the soil, what counts is what the participant himself experiences, his own emotion. The mythical images, therefore, are products, first and foremost, of spontaneous, collective emotions. The myth and ritual school, though they share many similarities with Frazer and the Cambridge School, ignore them. S. H. Hooke, an Old Testament scholar, was not interested in the magical origins of sacral kingship.

While Frazer and others held that all over the world rite and myth developed in comparable ways through spontaneous evolution, Hooke was not interested in development. Most importantly, he shifted the order: myth did not originate out of rite, but the other way round. The original Myth, inseparable in the first instance from its ritual, embodies in more or less symbolic fashion, the original situation which is seasonally reenacted in the ritual: everything that happens on earth corresponds with something that exists and happens in heaven and the earthly king is an image of the heavenly king.

(Sargon's background compares to that of Moses' rescue from a river and raised by others)

God came first and had always done so. Those who prefer to think that He Himself might have arisen from some earlier social ritual were welcome in libertine Cambridge. Anthropologists venture into the arguments surrounding myth and ritual: the myth is a system of word symbols, whereas ritual is a system of object and act symbols. both are symbolic processes for dealing with the same type of situation in the same affective mode. Another similar view states: myth is the counterpart of ritual: myth implies ritual, ritual implies myth, they are one and the same. Such statements can be explained if we think of the functionalist perspective from which these anthropologists operated. both myth and ritual were considered primarily as a symbolic means of giving sense, form, and definition to the social universe within which man functions as a social being.

Mary Douglas maintains that ritual is the institutionalized rhetoric of symbolic order. Substitute "myth" for "ritual" in this statement and the truth value remains the same. Robertson Smith was attacked by the emotional responses of orthodox clerical circles: "His mind is like a shop with a big cellar behind it, and having good shelves and windows....But he doesn't grow his own wool, nor does he spin the thread, nor weave the webs that are in his cellar or on his shelves. all his goods come in paper parcels from Germany."

Smith was dismissed from the chair of Old Testament studies of Free Church college in Aberdeen in 1881 for the blasphemous conviction that Moses could never have written the entire Pentateuch. Two years later he moved to Cambridge, where he came to hold a chair of Arabic. Theories, as Frazer himself said in his introduction to the third edition of The Golden Bough, are meant to give way to other information and ideas. Evolution of religion from magic is an outdated notion by now. Nor should we maintain the myth and ritual complex connected with the year king and the year god as a scheme for anything and everything, outside of which there is no salvation. Emil Durkheim's maxim was that as soon as a psychological explanation is suggested somewhere you may be sure that it is the wrong one. Myth, being the plot, may indicate connections between rites, which are isolated in our tradition. Rite is considered a necessary means of communication and solidarity within a social group.

Feigned fear and aggression may prevent real disaster. Myth, however, does the same with different means. Here, too, the theme is menace and death, but now the victims are human beings, whereas the ritual confines itself to animals: only the myth carries, in fantasy, to the extreme what, by ritual, is conducted into more innocent channels. "Ritual is action redirected for demonstration" -- Walter Burkert With many animal species living socially it has been found that certain types of group behavior possessed an evidently biological function originally, but became detached from their origin and acquired a new function: that of a communication signal, the effect of which is binding on the group.

These ritual acts are highly stereotyped, repeated and exaggerated, often manifested in theatrical and dramatic forms, and preeminently social action. Others noted that with humans, too, ritual behavior might become divorced from its original roots and acquire some new function fostering solidarity, such as mourning behavior. A great number of ritual customs are interpreted as ritualized, therefore stereotyped and "degenerate" biological actions. Myth is the verbal expression, rite a reflection in action, of essentially identical situations and their inherent psychic emotions. There are myths and rites that are so closely connected that many of us had already been under the impression that these, at any rate, must have originated simultaneously.