Enter Sigmund Freud

The episode of Yahweh’s

attack against His own prophet and messenger has been rendered by such extremes

as the authors of the Midrash to the likes of Sigmund Freud, which sets up our

journey into the mysteries of this text.

Freud’s least successful book, as judged by those who acknowledge his

indefatigable efforts in defining the bedrock theories of psychoanalysis, in all

the dozens of volumes of writing—done, by the way, at the writing desk and not

at the “couch”—was Moses and Monotheism (1939).

As a Jew, Freud had a love/hate relationship with his

race and its theological, sociological history.

Often referred to as “Godless Jew,” as if there existed redundancy and

hence extreme evil in the term, Freud did not adhere to the faith of his

fathers. For Freud, God and His

inspired religions and their faithful, represented the Oedipal Conflict on a

cosmic scale. However, he became

fascinated—if not obsessed—with this particular episode in Exodus and attempted

to explain it (interestingly, there existed several of these bête noirs

for Freud, such as the belief that Shakespeare had not written “Shakespeare”).

Freud’s “least successful” book, Moses and Monotheism, has been reviled,

misunderstood, and only recently has begun to enjoy a more favorable reading,

even as the reputation of Freud and psychoanalysis in general have suffered

correspondingly by those who maintain Freud’s theories are hopelessly out of

date and irrelevant in light of the “modern” cognitive theories of mind (that’s

admittedly another argument; but one must understand that with which he

disagrees in order to establish the priority of something different; so too,

people tend to forget that Freud always hoped that somatic reasons could be

found for neuroses and psychoses).

As a Jew, Freud had a love/hate relationship with his

race and its theological, sociological history.

Often referred to as “Godless Jew,” as if there existed redundancy and

hence extreme evil in the term, Freud did not adhere to the faith of his

fathers. For Freud, God and His

inspired religions and their faithful, represented the Oedipal Conflict on a

cosmic scale. However, he became

fascinated—if not obsessed—with this particular episode in Exodus and attempted

to explain it (interestingly, there existed several of these bête noirs

for Freud, such as the belief that Shakespeare had not written “Shakespeare”).

Freud’s “least successful” book, Moses and Monotheism, has been reviled,

misunderstood, and only recently has begun to enjoy a more favorable reading,

even as the reputation of Freud and psychoanalysis in general have suffered

correspondingly by those who maintain Freud’s theories are hopelessly out of

date and irrelevant in light of the “modern” cognitive theories of mind (that’s

admittedly another argument; but one must understand that with which he

disagrees in order to establish the priority of something different; so too,

people tend to forget that Freud always hoped that somatic reasons could be

found for neuroses and psychoses).

But Freud never

intended the charges and critical implications the work received, as a work

concerned with the establishment of the Oedipal Conflict on a grander scale, or

explanation for the nexus of Hebrew/Christian correspondence. That the book saw publication in 1939 lends itself to the

latter view almost by default, especially since Freud had moved abroad by this

time, one step ahead of Hitler’s police.

Freud saw the work as a “Historical Novel”—the qualifying, generic

distinction speaks volumes as to his intentions and the material with which it

deals. But, still, it came from

Freud, and therein lay the explanation of its relevance and intended audience.

What follows then serves as the gist of Freud’s historical novel.

Freud believed that the

passage in question, wherein Yahweh seeks to kill Moses in the desert,

represents a biblical “echo”; that is, the incident should have been deleted,

forgotten by later peoples, and never found its way to oral storytelling, much

less print (if peoples two millennia before Christ could conceive of such).

Freud is not alone in this idea; many aspects of an older, oral tradition exist,

but most have been synthesized into acceptable forms of redaction.

The scholar/writer Robert Graves gives us his well-known work Hebrew

Myths (with Raphael Patain, 1963), which, for instance, focuses on the oral

tradtions of the earliest of writings, such as Genesis 3: the Serpent and its

tempting manner in the Garden, for Graves and other mythologists, stands as an

echo of the Dragon of Chaos, and Adam’s first wife, Lilith, who, as the first

liberated woman, wished for equality.

She saw the act of lovemaking as

typical

male domination and desired other means for intercourse, which caused Adam

considerable problems. Forsaking

her mate, she liberates herself by coupling with the great god of Chaos and

breeds evil spirits, among whom may be found one god of evil who would

distinguish himself as Satan. Thus

the idea of a sanitized and much-changed narrative finds the Serpent showing up

in the Garden, after Yahweh has tamed and created out of Chaos, and seduces the

woman who succumbs to his power, partly because of her dissatisfaction with the

way women are disparaged.

typical

male domination and desired other means for intercourse, which caused Adam

considerable problems. Forsaking

her mate, she liberates herself by coupling with the great god of Chaos and

breeds evil spirits, among whom may be found one god of evil who would

distinguish himself as Satan. Thus

the idea of a sanitized and much-changed narrative finds the Serpent showing up

in the Garden, after Yahweh has tamed and created out of Chaos, and seduces the

woman who succumbs to his power, partly because of her dissatisfaction with the

way women are disparaged.

Freud believed that the

echo in question here, with regard to Yahweh attacking Moses in the desert,

represented something that historically took place, a thing so horrible and

traumatic for the people who engaged in it that they had to rewrite the story in

order to live with their guilt. Make no mistake: the story as Freud comes to believe is

certainly part of his Oedipal theory; however, all psychic development in

Freud’s view depends on this (these) traumatic circumstance.

He maintained that the children of Israel killed Moses in the wilderness,

and, suffering great guilt for the death of their father figure, the people had

to “invent” a second Moses, one who delivered them from evil and sent them on

their way to the Promised Land.

Freud’s research led him to believe that the echo of Yahweh seeking to kill

Moses inadvertently remained in the text, clarified as to its Oedipal crisis by

the manner in which Zipporah manages to dissuade God from taking Moses’ life

(circumcision or symbolic castration), and all that follows, with the rash

actions of the Hebrews in the wilderness and the apparent ease with which they

stray, even after a first-hand view of God’s power in the night of the “Passing

Over.”

Freud maintained that

the Israelites retold and rewrote their history so that no death occurred,

merely the threat, and that Moses maintained his grasp over the feckless,

backsliding Israelites. Moreover,

Freud maintains that various concern from the text, such as the inability of the

people to leave the inhospitable wilderness for such a long time—when Abraham

managed a much longer journey in a fraction of the time and braving worse

conditions—could not profitably be explained, except to say that time and its

corresponding confusion were attempts to expiate and muddy the waters as to what

truly happened. As a small token of

revenge in their collective memories, at least Moses does not reach the Promised

Land.

After Christian doctrine

had burst the confines of Judaism, it absorbed constituents from many other

sources, renounced many features of pure monotheism, and adopted in many

particulars the ritual of the other Mediterranean peoples.

It was as if Egypt had come to wreak her vengeance on the heirs of

Ikhnaton [Freud’s spelling for Akenaten].

The way in which the new religion came to terms with the ancient

ambivalences in the father-son relationship is noteworthy.

Its main doctrine, to be sure, was the reconciliation with God the

Father, the expiation of the crime committed against him; but the other side of

the relationship manifested itself in the Son, who had taken the guilt on his

shoulders, becoming god himself beside the Father and in truth in place of the

Father. Originally a Father

religion, Christianity became a Son religion: the fate of having to displace

the Father it could not escape (Freud 175-76).

Freud maintained that

Moses was, in fact, not a Hebrew at all, but the Egyptian pharaoh who ascended

the throne about 1375 B.C.E., named Akhenaten (who took the king name, Amenhotep

IV; like his father, he changed his name—he died in 1358), who believed in only

one god, the Sun, which was heresy for the priests of Egypt and their plethora

of gods and goddesses. This pharaoh overturned all that was “holy” in the name of heresy, a belief in one

god, and reversed all the most cherished religious practices and beliefs of his

people. These same people rose up,

overthrew the pharaoh, and sent him and his followers into exile in the desert.

There his people grew restless, rose up in agitation over their homelessness and

heretical beliefs, killed Amenhotep, and then suffered the guilt that children

go through in their infancy and before adolescence: the desire of the male child

to wish the father dead in order that he may possess the mother, and, should

some harm actually come to the father, the child suffers throughout his

life with the guilt for having not only desired the death, but somehow

possessing the power in which to effect it.

As a subtext to this idea, note how important women are in the earliest parts of

the narrative; they remain the desired objects of a people, most especially in

the episode of Moses at the well in Midia, for wells are thematically equated in

Scripture to a wife (Proverbs 1:15-16), a prostitute (Proverbs 23:27), or, if

sealed, a virgin (Genesis 29:2-10), and the word may pun between “drink,”

“kiss,” and “lust.”

pharaoh overturned all that was “holy” in the name of heresy, a belief in one

god, and reversed all the most cherished religious practices and beliefs of his

people. These same people rose up,

overthrew the pharaoh, and sent him and his followers into exile in the desert.

There his people grew restless, rose up in agitation over their homelessness and

heretical beliefs, killed Amenhotep, and then suffered the guilt that children

go through in their infancy and before adolescence: the desire of the male child

to wish the father dead in order that he may possess the mother, and, should

some harm actually come to the father, the child suffers throughout his

life with the guilt for having not only desired the death, but somehow

possessing the power in which to effect it.

As a subtext to this idea, note how important women are in the earliest parts of

the narrative; they remain the desired objects of a people, most especially in

the episode of Moses at the well in Midia, for wells are thematically equated in

Scripture to a wife (Proverbs 1:15-16), a prostitute (Proverbs 23:27), or, if

sealed, a virgin (Genesis 29:2-10), and the word may pun between “drink,”

“kiss,” and “lust.”

No historical

documentation exists to suggest that the Moses of Egypt or Israel ever existed.

But that should not deter us, anymore than specific evidence of Jesus

having lived remains “unprovable.”

Akhenaten instituted a monotheistic religion in the fourteenth century, B.C.E.

His established religion was forgotten immediately after his death: Moses

is a figure of memory but not history, while Akhenaten was a figure of history

but not of memory. But when we

speak of religion are we speaking of no more than a distinction between “us” and

“them”? Doesn’t every religion

establish what passes for barbarism and paganism even as it totes what and who

the “divine” and elected are? All

cultures establish this “otherness” in their construction of identity but also

develop the techniques of translation; that is, we must distinguish between the

“real” and the “other,” which always goes to the heart of determining self and

otherness, as well as constructing the Other to such a degree that it is

duplicitous and obviously dangerous, for it remains the shadow of individual

identity.

Polytheistic religions

overcame the primitive ethnocentrism of tribal religions by distinguishing

several deities by name, shape, and function.

The names are, of course, different in different cultures, because the

languages are different. The shapes

of the gods and the forms of worship may also differ significantly.

But the functions are strikingly similar, especially in the case of

cosmic deities; and most deities had a cosmic function.

The sun god of one religion is easily equated to the sun god of another

religion and so forth. Because of

their functional equivalence, deities of different religions can be equated.

The gods were

international because they were cosmic.

The different peoples worshipped different gods, but nobody contested the

reality of foreign gods and the legitimacy of foreign forms of worship. The Mosaic distinction was therefore a radically new

distinction, which considerably

changed

the world in which it was drawn.

The space, which was “severed or cloven” by this distinction, was not simply the

space of religion in general but that of a very specific kind of religion.

We may call this new type of religion “counter-religion” because it

rejects and repudiates everything that went before and what is outside itself as

“paganism.” It no longer functioned

as a means of intercultural translation; on the contrary, it functioned as a

means of intercultural estrangement.

changed

the world in which it was drawn.

The space, which was “severed or cloven” by this distinction, was not simply the

space of religion in general but that of a very specific kind of religion.

We may call this new type of religion “counter-religion” because it

rejects and repudiates everything that went before and what is outside itself as

“paganism.” It no longer functioned

as a means of intercultural translation; on the contrary, it functioned as a

means of intercultural estrangement.

All cultural

distinctions need to be remembered in order to render permanent the space, which

they construct. Usually, this

function of remembering the fundamental distinction assumes the form of a “Grand

Narrative,” a master story that underlies and informs innumerable concrete

tellings and retellings of the past.

The Mosaic distinction between true and false in religion finds it

expression in the story of Exodus.

In the space that is constructed by the Mosaic distinction, the worship of

images came to be regarded as the absolute horror, falsehood, an apostasy.

Polytheism and idolatry were seen as the same form of religious error.

The second commandment is a commentary on the first:

-

Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

-

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.

Images are

automatically “other gods,” because the true god is invisible and cannot

iconically be represented.

Exodus is a symbolical

story, the Law is a symbolical legislation, and Moses is a symbolical figure.

The whole constellation of Israel and Egypt is symbolical and comes to symbolize

all kinds of oppositions.

But the leading one is the distinction between true religion and

idolatry. Some poignant verses in

Deutero-Isaiah and Psalm 115 develop into whole chapters in the apocryphal

Sapientia Salomonis and long sections in Philo’s De Decalogo and

De Legibus Specialibus.

This hatred was mutual

and the “idolaters” did not fail to retaliate.

Understandably enough most of them were Egyptians.

For example, the Egyptian priest Manetho, who wrote an Egyptian history

under Ptolemy II, represented Moses as a rebellious Egyptian priest who made

himself the leader of a colony of lepers.

Whereas the Jews depicted idolatry as a kind of mental aberration, of madness,

the Egyptians associated iconoclasm with the idea of highly contagious and

bodily disfiguring epidemic. The

language of illness continues to typify the debate on the Mosaic distinction

down to the days of Sigmund Freud.

This story about the lepers originally referred not to Moses, but Akhenaten, who

was the first to establish a monotheistic counter-religion and to draw the

distinction between true and false.

But after this death, his religion was abolished, and his name fell into

complete oblivion. The traumatic

memories of his revolution were encrypted and dislocated; eventually they came

to be fixed on the Jews.

When Sigmund Freud felt

the rising tide of German anti-Semitism outgrowing the traditional dimensions of

persecution and oppression and turning into a murderous attack, he—remarkably

enough—did not ask the obvious question of “how the Germans came to murder the

Jews”; instead he asked, how “the Jew came to attract this undying hatred.”

He embarked on a project very different from his normal work.

This “historical novel,” as he first called it, was a rather private

undertaking, a kind of “day-dreaming,” which underwent many transformations

before it was finally published as a book.

His quest for origins

took him as far back as Akhenaten and his monotheistic revolution.

In making Moses an Egyptian and in tracing monotheism back to ancient

Egypt, Freud attempted to deconstruct the murderous distinction.

It is the same method of deconstruction by historical reduction that

Nietzsche had used in his Genealogy of Morals.

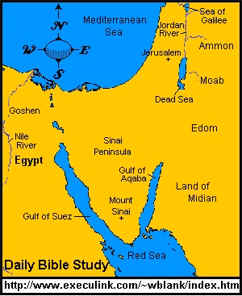

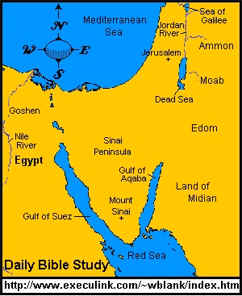

But to understand properly what we’re saying here means understanding

that Egypt and Israel, both North and South, were neighbors, sharing both

political, ideological, commercial, and complex associations.

Thus, for one of the these countries, along with several others, to break

the relationship by not evolving but breaking—revolution as opposed to

evolution—that bond obviously meant trouble.

We seem to think that

monotheism represents progression and “modern” views in contrast to polytheism;

it does not. Monotheism always

appeared as counter-religion to the status quo or the conservative,

traditional way. Imagine, if you

will, the difficulty that anyone would have today in establishing a new thought

that ran counter to that most of us accepted, and, most especially, the middle

road of conservatism in our nation.

America is and has always been a very conservative nation, so that

we even shy away from the thought of a Roman Catholic occupying the White House,

to say nothing of a Jew or African-American.

What we call “liberalism” in America is the middle way to most European

nations, and even represents conservativism in many.

Anything that changed the conservative nature of our religious beliefs

would be attacked in America, but how much more so by the well-known,

well-connected most conservative of Christians, such as Pat Robertson or Jerry

Falwell? How could one possibly

stand against their onslaught of money, influence, television time and

opportunity?

So, in order for us to assimilate

these terms and ideas, it becomes necessary to repeat some of them, if briefly,

in order clearly to establish the concept so that we may move on to the later

significances. The Exodus

represents a story of migration and conversion, of something radical, of

something that separates the old from the new: Egypt represents the old, while

Israel represents the new. In terms

of cultural memory, this becomes the “memory of conversion.”

And in this new way of thinking, the old ways, the ways of memory for a

people say that idolatry is forgetting and regression, but monotheism means

remembering and progression. The

term for cultural memory as a people who can and do go back to some pertinent

event in their history, which represents more than an act but designates who and

what they are, has come to be termed “Mnemohistory” (Mnemosyne was the mother of

the nine

muses; the name suggests “memory” and the totality of cultural activities).

While not the opposite of history, the term means a branch, whether social or

intellectual or even cultural that leaves aside the synchronic events of what is

happening or is investigated; it focuses on the products of history or

memory, a recourse to the past that can only become clear when we have read,

participated, or become influenced in many areas of our history.

In other words, history is no longer transmitting and receiving: we

become haunted by our past as it encroaches on everything we do.

muses; the name suggests “memory” and the totality of cultural activities).

While not the opposite of history, the term means a branch, whether social or

intellectual or even cultural that leaves aside the synchronic events of what is

happening or is investigated; it focuses on the products of history or

memory, a recourse to the past that can only become clear when we have read,

participated, or become influenced in many areas of our history.

In other words, history is no longer transmitting and receiving: we

become haunted by our past as it encroaches on everything we do.

Memories easily change,

as we’re coming to learn and which, even as I write this, have been distorted,

falsified, invented, and implanted.

Just recently a researcher demonstrated this by implanting the idea of

memories within people who had visited one of the Disney theme-parks, suggesting

that they had visited with “Bugs Bunny” while there and had pleasant memories

associated with what they did and what their children saw, etc., when Bugs

approached them. They recalled it

vividly, enough to swear it happened, only to learn that Bugs Bunny is a Warner

Brothers character, not one of the Disney stock.

Memory is only a valid, historical source if checked by “objective”

evidence. But for historical

researchers, history lives only if it made an impression on the

collective memory, and if it makes no impression it is easily forgotten.

And so, for the

historicist, the task remains to separate historical facts from mythical

elements, and then to distinguish those elements of the past as they shape or

impinge upon the present. However,

for the mnemohistoricist, the truth exists in analyzing the mythical elements of

the past and attempting to understand their hidden agenda.

In this instance, the problem is not was Moses aware of and trained in

the life of Egypt, but rather why his Egyptian life and ways is not

presented in the book of Exodus—and, moreover, why is not in the Hebrew text of

Exodus but is in the Christian text of Acts 7:22?

This is somewhat akin to forgetting that Paul was a conservative Jew, who

comes to bridge the gap between Jews and Christians in our thinking, but in

terms of his time he was as much different from today’s Christians as one

can imagine, an ambivalent figure in Jewish messianism.

This counter-memory goes even further, stating that “you remember it this

way, but I remember it differently…because I recall what you have forgotten.

We forget that the line between history and myth is one of continuous movement:

history turns into myth as soon as it is remembered, narrated, and used in such

a way as to be woven into the fabric of our present.

The question that now

must be addressed is what is the cultural memory of the Jews and Egypt,

what is it or how does this cultural memory differ from historical events

in terms of objective portrayal or evidence passed onto the Jews, and by way of

the Jews to Christians in their time (when they first differentiated

themselves from Jewish thought and belief) and our own?

One must first go back to the Renaissance (originally an art history term

of the nineteenth century, designating the “new birth” of classical thought that

transpired in the late fourteenth century in Southern Europe and later, in the

early sixteenth century, in the North).

This was the “golden age” of the Egyptophilia.

The second wave occurred in the Napoleonic expedition to Egypt, when

hieroglyphic script was first deciphered, in the next century.

The interest in all things Egyptian was such that the nineteenth century

firmly believed that the nation was the “origin of all cults.”

Where are we headed?

The answer to that remains far easier than the explanation.

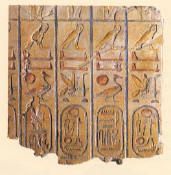

Moses was an Egyptian—the question, however, is still one of who Moses

was: Akhenaten, perhaps? Akhenaten,

or Pharaoh Amenophis IV, became erased shortly after his death from all the

king-lists, monuments, inscriptions, and anything that bore his name—this from a

people who were scrupulous in their

historical

lists (from which much biblical historicity is gathered, given that the Bible

may be the only evidence for the existence of many people).

It was not until that great age of the Nineteenth Century that he became

known once again. The difficulty

here is that Akhenaten existed, but there is no memory of him, while Moses has

been recalled in memory, but no physical, historical evidence survives to prove

his existence.

historical

lists (from which much biblical historicity is gathered, given that the Bible

may be the only evidence for the existence of many people).

It was not until that great age of the Nineteenth Century that he became

known once again. The difficulty

here is that Akhenaten existed, but there is no memory of him, while Moses has

been recalled in memory, but no physical, historical evidence survives to prove

his existence.

Whoever Moses was, he

destroyed and abolished all cults and idols of Eyptian polytheists and

established a purely monotheistic religion—for Akhenaten, that meant the god of

light, whom he called Aton.

Scholars of Eyptology and the Moses connection look, for instance, at Psalm 104

and ask if this is not a hymn to the Egyptian god translated into Hebrew.

Moreover, they ask if Aton and the Hebrew Adonai (“Lord”) are not the

same and from the root noun. This

pharaoh is the one that Freud argued in his “historical novel” was really Moses.

But because he saw the resurrection, so to speak, of a second Moses once they

had killed the first as a continuation of their need for a hero, a leader, and

one they could look back upon with fond memory and to establish who and what

they were, many mistook the Oedipal associations of a people acting in concert

and collectively the way that Freud had argued for the individual’s struggle

with selfhood and maturation as the raison d’être of the work.

While it fit perfectly with Freud’s schema, the book was not intended as

psychoanalytic theory but conjecture, and that with considerable license, as

with all fiction.

What, you may ask, has

all this to do with a leader who lived in the mid-fourteenth century B.C.E., and

ruled for a brief seventeen years?

Because, this is the same time as our biblical Moses.

And one can go back further for several more centuries to remembered

events in this part of the world that would influence its people: the Hyksos

invasion of Palestinian invaders who lived and ruled Egypt for one hundred

years. They, however, lived and

conformed to the polytheistic way of the people whom they conquered, but they

were driven out in such a way that those retelling the stories of Akhenaten and

trying to explain his “evil ways” could impart a different cultural memory.

Is what the people suffered through their traumatic recollection (and

traumas cause memories—to such an extant that people sometimes forget them but

carry their influences in the lack of speech, sleep, terrible episodes brought

about by seemingly irrelevant events or triggers, and the like, so that traumas

are bad enough that our entire being attempts to erase them as best as possible)

part of their displeasure and upheaval over the first monotheist converting

through power the nation into monotheism? One argument for the idea of

trauma comes to us from this age, referred to as the Armana age, when the

Hittite Empire raided an Egyptian garrison and brought with them plague, one

that raged for as long as twenty years.

The feasts in ancient

Egypt were the only occasion when the gods left their temples and appeared to

the people at large; otherwise, they dwelt entirely in darkness inside the

sanctuaries of their temples, inaccessible to all but the most select of

priests. All feasts took the form

of processions, when the gods appeared outside the city walls; thus the city is

where people wanted to be, to be buried, to find their gods, to associate with

the priesthood: the more important the god or procession, the more important the city and vice versa.

Can one imagine a period of time when disease spreads by the contact of

individuals within the city? To

stop this and to deprive the people of their feasts and associations with their

gods must have caused enormous turmoil and trauma.

Conjoin this with the idea of the trauma of one bringing a new religion, one

different than all of their past, and one can understand how cultural memory

wishes to link the two and recall them as one.

The Asiatic illness—leprosy?—soon finds itself in association with the Hyksos’

god Baal, who is associated with the Egyptian god Seth.

It is at this time that the Egyptian god Seth begins to become a god of

“otherness,” of characteristics of a devil and Asiatic foreigner.

important the city and vice versa.

Can one imagine a period of time when disease spreads by the contact of

individuals within the city? To

stop this and to deprive the people of their feasts and associations with their

gods must have caused enormous turmoil and trauma.

Conjoin this with the idea of the trauma of one bringing a new religion, one

different than all of their past, and one can understand how cultural memory

wishes to link the two and recall them as one.

The Asiatic illness—leprosy?—soon finds itself in association with the Hyksos’

god Baal, who is associated with the Egyptian god Seth.

It is at this time that the Egyptian god Seth begins to become a god of

“otherness,” of characteristics of a devil and Asiatic foreigner.

To try and recast this

explanation into summarized form, we find that the Armana period, that which saw

the pharaoh break with all tradition and to institute a religion of but one god,

not many, retrospectively shapes a collective memory of the Hyksos occupation,

of disease and foreignness, so that for the Egyptian memory is associated with

all that represents this “otherness,” which finds its way to projection upon

Jews. Jews remember the experience

one way, Egypt another. Ancient

historians, such as Josephus, write of the terrible period as being brought

about by the Jews: as Egypt remembers the events, they cast out the unclean,

disease bearing and ungodly Jews; as Hebrew memory has it, a leader rose up and

released them from the bondage of living among pagans, visiting upon them

numerous dire and plague-filled wonders from their god.

The Egyptians remember the savage Hyksos, Palestinians, while the Jews

remember Pharaoh and his “strengthened heart.”

The argument for this

cultural memory and what has changed or how it has been remembered is,

admittedly, poorly rendered here, and I would urge the reader to consult Jan

Assmann’s work, Moses the Egyptian, Freud’s Moses and Monotheism,

the work of anthropologist and sociologist Mary Douglas, or a host of other

sources in the study of both religion and Egyptology. But the most important principle here, especially in terms of

literature, is to remember that all is fiction. And by that we do not denigrate biblical narratives; we

merely remind the reader that all events, whether purported to be fiction or

fact, render perspective and recall events and their selective memories as

biased points of view. Such a

perspective does not render something “untrue,” but it goes back to the concept

discussed in another essay that “truth” exists by correspondence or

coherence—one may judge the “rightness” of something by how it corresponds

to know facts, those we feel comfortable with and have come to accept without

question, or one may see events by their totality and how they cohere to a

larger idea, since some of the parts may be symbolic, metaphoric, or used for

illustration.

Note, however, that

polytheism is not ignorance or immaturity with regard to a culture; on the

contrary, it represents a much more sophisticated form of interaction between

peoples. Two entirely different

races may call their gods by different names but they agree on the existence of

the god and the power exhibited.

Many of the gods of monotheism, in fact, derive from a single source,

acknowledged by the believers, which attribute not to gods, but God (this God is

called by many names but answers to the “true name,” distinguishing its rightful

source.

I invoke you as do the Egyptians:

As do the Jews: Adonaie Sabaoth

As do the Greeks: king, ruling as monarch over all,

As do the high priests: hidden one, invisible one, who looks upon all,

As do the Parthians: OYERTO almighty.

(Papyrus Leiden I, 384)

Or,

The sons of Ogyges call me Bacchus,

Egyptians think me Osiris,

Mysians name me Phanaces,

Indians regard me as Dionysus,

Roman rites make me Liber,

The Arab race thinks me Adoneus,

Lucaniacus the Universal God.

(Epigram 48 of Ausonius)

The crime that

Akhenaten committed was to dismiss all power into but one source, the Sun.

Priests would tell the people that this caused the plague, disease,

death, and that the only way to regain favor with “the” Deity was to expel those

who brought the contagion. In fact,

the story of Moses circulated among many different peoples, in many cultures,

and in many narratives (including one of the First Century B.C.E., where the

leaders of the people are named Joseph and Moses, much like a later rendering of

two different people at two vastly different times having to do with the

Egyptians and escape).

The point here is that

one religion may give way, and often does, to a counter religion that

attempts to revile the former and in everyway appear as different.

In the study of literature, for instance, it is commonplace to accept and

to identify the fact that every age disparages the previous; it attempts to move

as far away as possible. And yet,

by its very insistence upon difference, it points up all the more its

similarities—the idea of Gertrude stating in Hamlet that “the lady doth protest

too much.” In other words, Gertrude

notes that the Player Queen makes too much out of denial and therefore points to

her own guilt (much as Claudius does in the play, Hamlet). The argument that the literature concerning Moses reveals

“protestation” by the people who adhere to its tenets rests in everything that

the revealed religion demanded: monotheism is the counter-religion; no zooistic

or animal-like powers and deities may be demonstrated; dietary laws are

essential; the people are separated from their gods due to impurity, and so the

gods cannot come out to visit them from the city, and the people were not

expelled—they revolted and left of their own accord, having first struck the

land with a plague.

Here

are a few questions

and observations for the reader to consider with regard to the

Exodus and Moses narratives:

Note how little we know

about the early Moses, his confrontations that lead to his self-imposed exile

(must he flee?), the lack of control in all of this (is God directing Moses or

is this pure providence?—and what does that mean?); the restraint he shows when

dealing with the invaders at the well—only scaring them off as opposed to

killing them.

Moreover, Moses

demonstrates progressively restrained tendency from the first killing of the

Eyptian taskmaster. After the encounter at the well in Midian, he has the

opportunity to meet the seven daughters of Reuel. Note that the well or spring was, as it is now, life

to the Bedouins. But there’s more:

the spring or well is a female symbol: a wife (Proverbs 1:15-16); a prostitute

(Proverbs 23:27), or, if sealed, a virgin (Genesis 29:2-10; Cant. 4:12; and

Cant. 1:2 (which develops a pun between drink, kiss, and lust [p. 175]).

daughters of Reuel. Note that the well or spring was, as it is now, life

to the Bedouins. But there’s more:

the spring or well is a female symbol: a wife (Proverbs 1:15-16); a prostitute

(Proverbs 23:27), or, if sealed, a virgin (Genesis 29:2-10; Cant. 4:12; and

Cant. 1:2 (which develops a pun between drink, kiss, and lust [p. 175]).

The bond is greater

between Reuel (sometimes referred to as Jethro) than between Moses and Zipporah—why?

Does he look rich? But they

would have feared and loathed the Egyptians.

Does the narrative smack of the testing of Isaac and Rebekah—also, Reuel

has nothing but daughters. Then

again, this isn’t romantic, but political and religious as opposed to

patriarchal and matriarchal.

Note the bond between

Israel and Midian: Gen. 4:1-16

paints these people as murderers; they kidnap Joseph; P won’t deal with them in

his narrative—who omits Moses sojourn among them, that his wife came from Midia.

P would have nothing to do with them; only the older texts of J and E come

through with this information.

Exodus 2:23-25: “And

Deity remembered his covenant.” J

and E give us suspense, where we believe that the God behind this must make

Himself known; however, the redactor detached this from 6:2, from P; as it

stands here, it demonstrates Yahweh’s universal scope, even interrupting a

pastoral description that Israel’s suffering continues.

But the most striking feature of this passage is that Elohim is repeated

five times. This signals the lack

of detachment from His place in the world—no more behind the scenes, but now

actively taking part.

Moses claims to be

heavy of mouth and heavy of tongue—he attempts to dissuade Yahweh: Chapter 4,

verse 14: “then Yahweh’s nose grew angry at Moses…”

Notice the mix of senses.

Yahweh points out that Aaron approaches, his fellow Levite. Yahweh tells him that He will “strengthen his heart” that

Pharaoh won’t believe.” Also, Moses

gathers his woman and his possessions and saddles his ass—does this seem like

the Christian Scriptures?

Verse 24-25 is the

troublesome passage of Zipporah saving Moses from death.

Verse 26: “A bridegroom/son-in-law of bloodiness by circumcision.”

Then Yahweh speaks to Aaron: “Go to meet Moses to the wilderness.”

What happens here? Is this belated punishment for having killed a man in

the heat of anger? Or is there other significances to Moses' being saved

by his wife?

Verse 29: “And Moses

and Aaron went and assembled all of the elders of Israel’s Sons, (30) and Aaron

spoke all the words that Yahweh had spoken to Moses, and he did the signs before

the people’s eyes. (31) And the

people trusted, and they heard that Yahweh acknowledged Israel’s Sons and that

he beheld their oppression. And

they knelt and bowed down. Is this an indication of the Priestly writer, a

way to work the importance of the line of priests from Aaron into this important

narrative?

Exodus 3-4 offers the

best evidence for the Documentary Hypothesis, most especially J and E.

Distinguishing from P is much easier here—but that between J and E is the

problem. E calls Moses’

father-in-law Jethro, rather than Hobab or Reuel, as well as referring to the

Deities mountain as Horeb. As well,

E gives us Aaron as Moses’ interpreter.

Many echoes of Genesis, where the E writer is easy to spot are here in evidence

as well: “moreover, see: him coming out to meet you” is repeated in Gen. 32:7

and Exodus 4:14. Does E give us the Aaron importance because of the

division of the kingdom when he wrote, where North and South are separate, but

the Priests coming from the North?

Exodus 3:7 & 9

represent doublets. Later, specific

mentions of “hiding his face,” or removing his sandals” are both evidence of J

and E—never P. The strange sequence

of events here seems to be the work of the Redactor: Aaron’s mission seems often

misplaced in the narrative, where he receives his call, where Moses meets him,

to say nothing of the bridegroom of blood incident.

The most momentous

change wrought by the combination of J and E involves the divine name.

In E. the scene at Horeb is the climactic moment when God first reveals

his proper name to Moses, Israel and the world.

In JE, the meaning of the scene is entirely changed.

Since the name “Yahweh” was already known to the Patriarchs (e.g., Gen

15:2[J]), Moses’ request for God’s true name (3:13[E]) implies either that Moses

is testing the bush (cf. Deut 18:20-22; Judg 13:17) or that the name of the

ancestral god had been forgotten by Israel, or at lest never been taught to

Moses. If Moses himself never

learned the name, he is presumably preparing himself for interrogation by a

skeptical people (Jacob 1992: 65-62; and Comment, pp. 223-224).

One may find in various newer

biblical translations that Moses and the Hebrews do not have the Red Sea part

for them by God; rather it is the Reed Sea. This would have been the case

in terms of their journey out of Egypt--and the reeds that were used in so much

of their writing (papyrus) and building materials, such as bricks, grow only in

fresh, not salt water. A translator's error has been compounded throughout

the years (centuries) incorrectly translating Red for Reed, so that with more

modern translations that have gone back to older, more reliable translations

(for remember that all biblical material is translation, from translation, from

translation), the substitution of Reed for Red is natural. Older, more

venerated translations, such as the King James Version, hold onto the incorrect

"Red Sea" for the departure out of Egypt.

Finally, we must

observe several contributions of the Redactor: he is probably responsible for

4:21b, “But I, I will strengthen his heart, and he will not release the people.”

We have already been advised that Pharaoh will be uncooperative (3:19 [E]); now

we are assured that this is God’s plan.

Had the Redactor inserted his comment between vv 23 and 24, he would have

destroyed Redactor’s association of Pharaoh’s son with Moses’s son.

Instead, he set his interjection between references to the coming

“wonders” (i.e., the Plagues) and the slaying of the firstborn.

Exodus 4:21b later becomes the refrain of the Plagues cycle (7:13, 22;

8;11, 15; 9:12, 35; 10:20, 27; 11:10-11).

The Redactor’s work also created new implications and associations.

“Aaron your brother [i.e. “fellow”] Levite” (4:14[E]; becomes Moses’ full

brother 6:20 [R]. The valuables

taken from the Egyptians (3:22; 11:2-3; 12:35-36[J?] are no longer mere booty.

In the composite Torah, they are presumably used for building the Tabernacle

(chaps. 25-31, 35-40 [P]).

As a Jew, Freud had a love/hate relationship with his

race and its theological, sociological history.

Often referred to as “Godless Jew,” as if there existed redundancy and

hence extreme evil in the term, Freud did not adhere to the faith of his

fathers. For Freud, God and His

inspired religions and their faithful, represented the Oedipal Conflict on a

cosmic scale. However, he became

fascinated—if not obsessed—with this particular episode in Exodus and attempted

to explain it (interestingly, there existed several of these bête noirs

for Freud, such as the belief that Shakespeare had not written “Shakespeare”).

Freud’s “least successful” book, Moses and Monotheism, has been reviled,

misunderstood, and only recently has begun to enjoy a more favorable reading,

even as the reputation of Freud and psychoanalysis in general have suffered

correspondingly by those who maintain Freud’s theories are hopelessly out of

date and irrelevant in light of the “modern” cognitive theories of mind (that’s

admittedly another argument; but one must understand that with which he

disagrees in order to establish the priority of something different; so too,

people tend to forget that Freud always hoped that somatic reasons could be

found for neuroses and psychoses).

As a Jew, Freud had a love/hate relationship with his

race and its theological, sociological history.

Often referred to as “Godless Jew,” as if there existed redundancy and

hence extreme evil in the term, Freud did not adhere to the faith of his

fathers. For Freud, God and His

inspired religions and their faithful, represented the Oedipal Conflict on a

cosmic scale. However, he became

fascinated—if not obsessed—with this particular episode in Exodus and attempted

to explain it (interestingly, there existed several of these bête noirs

for Freud, such as the belief that Shakespeare had not written “Shakespeare”).

Freud’s “least successful” book, Moses and Monotheism, has been reviled,

misunderstood, and only recently has begun to enjoy a more favorable reading,

even as the reputation of Freud and psychoanalysis in general have suffered

correspondingly by those who maintain Freud’s theories are hopelessly out of

date and irrelevant in light of the “modern” cognitive theories of mind (that’s

admittedly another argument; but one must understand that with which he

disagrees in order to establish the priority of something different; so too,

people tend to forget that Freud always hoped that somatic reasons could be

found for neuroses and psychoses). typical

male domination and desired other means for intercourse, which caused Adam

considerable problems.

typical

male domination and desired other means for intercourse, which caused Adam

considerable problems. pharaoh overturned all that was “holy” in the name of heresy, a belief in one

god, and reversed all the most cherished religious practices and beliefs of his

people.

pharaoh overturned all that was “holy” in the name of heresy, a belief in one

god, and reversed all the most cherished religious practices and beliefs of his

people. changed

the world in which it was drawn.

changed

the world in which it was drawn.

historical

lists (from which much biblical historicity is gathered, given that the Bible

may be the only evidence for the existence of many people).

historical

lists (from which much biblical historicity is gathered, given that the Bible

may be the only evidence for the existence of many people). daughters of Reuel. Note that the well or spring was, as it is now, life

to the Bedouins.

daughters of Reuel. Note that the well or spring was, as it is now, life

to the Bedouins.