<<

{click on image to view more}

Download

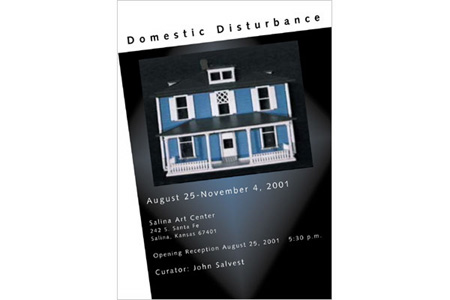

Exhibition Brochure (PDF) Domestic Disturbance

August 25–November 4, 2001

Salina Art Center, Salina, Kansas

Curated by John Salvest

"The familiar is not necessarily the known." –Hegel

The house in which I grew up was a two-story colonial style residence

built by my parents. Our family lived in it from December 1962 through

December 1994. I carry that house around with me at all times. I

can vividly recall all its details—wallpaper and upholstery

patterns, tile and carpet colors, the smell of the hamper and the

sound of the front gate closing. An inventory of furniture, appliances,

curtains, pillows, mirrors, rugs, lamps, clocks, televisions, radios,

houseplants and knickknacks specific to that house still exists

in a climate-controlled storage compartment in my mind.

I stopped living there on a regular basis when I married and took

my first real job. That was some ten years before my parents finally

moved away. But I have never really stopped living there, even now.

It haunts me like a sometimes cruel and sometimes benevolent ghost.

No matter what house I have lived in or will ever live in, its sights,

sounds and smells will always be overlaid upon that structure. Its

foundation, leaky basement and all, is the foundation for all houses

that follow. Every staircase I climb is its staircase. Every ringing

doorbell I answer is its doorbell. Every yard I mow is its tiny

postage stamp of a yard. Everywhere I sleep, I am still sleeping

there.

385 Chestnut Street was the stage set for an unfolding drama of

more than thirty years. In various combinations depending on college,

jobs and marriage, five people (and, for a while, a dog) shared

its rooms. It was the setting for my own coming of age and for the

dynamic psychological interplay between personalities. Mother, father,

sister, brother. Any relationship I have had or will have with another

human being is an extension of those relationships. I cannot separate

who I am from that house and its inhabitants. With little mental

effort, my eyes glaze over and I am transported back to its kitchen,

dining room, basement or bedrooms. Convince me that I am not now

sitting in the living room watching light reflect off cut glass

on the mantel of the never-used fireplace. With each room I can

easily envision a hundred happy and sad episodes, moments of high

drama and daily routine from a story that is, like your own, more

complex and mysterious than any work of fiction could ever hope

to be.

These daydreams have a surreal quality. Events do not necessarily

follow in chronological or even logical order. Years overlap; seasons

intermingle. In this ghost of a house I too move like a spirit.

In it I travel from second floor to basement in an instant, foregoing

temporal and spatial laws. In it I have x-ray vision as well. Closet

doors and cabinet covers suddenly turn transparent, revealing their

neatly arranged contents. The images in my brain are lifelike yet

slightly distorted. In my mental photograph of a room, one particular

piece of furniture may, inexplicably, loom large and dominate its

space unnaturally. Appliances and furniture mutate like Alan Topolski's

Houseware. As with Greely Myatt's Rug, a fragment of memory is all

that is necessary; objects complete themselves. Instead of the advancing

and receding cricket song in Amy Jenkins' Almost Home, the soundtrack

for my imaginings is the back-and-forth roar of a vacuum cleaner.

Like a fur-lined teacup, what appears in my mind's eye is at once

both familiar and strange.

Despite the strangeness of these domestic daydreams, it is a relief

to leave today's troubles behind and a comfort to know that what

is past is not completely lost. But my reveries are not entirely

blissful. A tension exists between nostalgic longing and a creeping

uneasiness. A feeling as vivid as a flatiron with upholstery tacks

tells me that my visit has been long enough and I am ready to return

to the present. After all, was not the groundwork for all future

woe as well as joy laid in those times?

In composing Domestic Disturbance, I was looking for artists whose

work seemed to possess the same conflicting qualities as my domestic

daydreams – ordinary and unusual, comforting and unsettling,

rational and irrational, humorous and sad. I suppose that I was

casting about for work that felt like the memories of home I carry

around inside me—familiar enough to comfort yet strange enough

to disturb.

Throughout my search, I used Man Ray's famous sculpture Cadeau (Gift)

as my guide. With one physically simple but psychologically complex

gesture, he transformed a common household object into a seductive

yet menacing icon that precisely reflects the oftentimes contradictory

nature of domestic life.

Like that wonderfully evocative work, the objects, installations

and videos in this exhibition all explore a zone of tension between

the familiar and the unexpected. Frequently that tension finds release

in humor. Nervous laughter results when a slightly overweight viewer

realizes that Brian Wasson's Scale does more than supply raw data.

With playful ruthlessness, it immediately calculates for its victim

his or her ideal height based on weight. For those unhinged by a

hair in their soup or on their soap, it is hard not to laugh and

cringe simultaneously at the nightmarish grout on a section of bathroom

wall in Barbara Kendrick's Caught.

You may notice the lack of physical human presence in Domestic Disturbance.

Except for a woman nervously (and silently) partaking of a midnight

snack in Dawn DeDeaux's Woman Eating Porkchop and a few unspeaking

residents of Nic Nicosia's Middletown, there are no people among

these domestic props and settings. Andy Yoder's table is set, but

there are no guests. Ernesto Pujol's Crib is childless. No one wears

Les Christensen's silverware wings or her oversized wedding dress

made of broken dishes. The only witness to the unusual events in

Gerald Guthrie's tiny room is a giant human eye—your eye.

You, the viewer, are the human presence, free to inhabit these odd

spaces and examine these strange artifacts that are at once, somehow,

both comforting and disturbing.

<< |